It’s a touchy subject, this feeding lark. When breastfeeding mothers and formula feeding mothers lock horns, the result bares likeness to a libyan battleground. On internet message boards across the globe, formula feeders are attracted to breastfeeding threads like moths to a flame. One group must offer a disclaimer before they open their mouth; the opposing group is ready with their straw men. Woe betide any breastfeeding mother who openly admits to having preference, knowledge and even *gasp* pride in nursing her child.

What’s more, the melee doesn’t end online. In day to day life the mother in law, the health professional and the random bod on the street jump in on a regular basis. They offer ‘advice’ fuelled by their own prejudice, defensiveness and lack of knowledge. Sometimes the advice is cloaked in the farce of ‘concern’; other times it is tantamount to brazen bullying.

Here’s my timely guide on how to tackle each irritant, one by one.

Formula feeders:

Argument: “Most of our generation were formula-fed and we are all healthy”.

Comeback: This is untrue. The long-term effects of not being breastfed are only beginning to be understood. Blood pressure, cholesterol levels, obesity, allergies, diabetes and academic performance are all starting to be linked with how we were fed as babies. We have more vision problems, intestinal problems, colds and flu, dental problems, heart problems, and cancer than we need to; And we’re a few IQ points lower than we would have been if we had been breastfed.

Argument: “My formula-fed kid turned out just fine and went to college and university”.

Comeback: Numerous studies have shown that breastfeeding is associated with significantly higher scores for cognitive development than formula feeding (see for example Horwood LJ and Fergusson DM). A difference of at least 3.16 points has been measurable through 15 years. It is important to realise that a child with a genetic potential for an IQ of 150 will probably not notice a 3.4 point deficit. A child with a potential for an IQ of 100 would benefit from 3.4 points. In other words, breastfeeding allows an infant to reach his/her full potential.

Argument: “My formula-fed kid has never had an allergy but my friend’s breastfed kid has several allergies, really bad eczema, hives, a bad cough and a low IQ so breastfeeding can’t be that protective” [or insert other personal anecdote here].

Comeback: Anecdotal evidence is not necessarily representative of a “typical” experience. Statistical evidence more accurately determines how typical something is. For example “I know a breastfed baby with eczema” does not disprove the proposition that “breastfeeding significantly reduces a child’s risk of eczema”. A ‘study’ of one, or two, or three or even four, does not negate a collection of studies which look at thousands of cases – as any schoolchild knows, surely? Also, a breastfeeding mother who has a baby with eczema can be virtually certain that her feeding choice did not contribute to the development of eczema. A formula feeding mother cannot be so sure.

Argument: “Why do breastfeeders try to make us feel guilty? It’s my choice how I feed my baby”

Comeback: Choice, of course, only exists when options are fully available, including information regarding the consequences of different methods of infant feeding. “The continued denial of the risks of not breastfeeding and the value of breastmilk supposedly to spare women’s feelings, is a patronising deception” (Palmer.G). Why is it that advertising formula is just business, but promoting breastfeeding is “pushy”? Mothers should have the opportunity to make an informed choice based on fact rather than anecdote. As parenting blog, An Unschooling Adventure has maintained: “Please mothers. Inform yourselves about the risks of formula. Stop blaming women who promote breastfeeding for trying to make you feel guilty, and target your anger towards the formula companies that have lied to you, or the health professionals that undermined your instincts.” While we’re on the topic of ‘choice’ – a highly cherished value of formula feeders – one burden of having choice is that one must be held accountable for one’s choice, a topic I discuss in length in my book ‘Breast Intentions’. If you feel guilty of your choice, that is your internal accountability system being triggered.

Argument: “Breastfeeders that drone on about the benefits of breastfeeding are smug, self-righteous and judgemental.”

Comeback: This is a straw-man argument. It is a misrepresentation of a breastfeeder’s position, created by the formula feeder for the express purposes of being knocked down. You see, everybody needs a victory or two for purposes of morale. If real ones are nowhere to be had, the formula feeder will wallop out a straw man.

In reality, the level of assumed smugness/judgeyness depends on the agenda of the person hearing the information not the person giving it. If someone finds criticism in statistics, I would suggest they are feeling defensive about their choices. Medics, the government, scientists and researchers have a duty to tell us what they know, and that is the obvious – that human mothers provide optimal nutrition for human babies. As parents don’t we have a duty to engage with such information?

Argument: “Why do breastfeeders try to make us feel guilty? It’s my choice how I feed my baby”

Comeback: Choice, of course, only exists when options are fully available, including information regarding the consequences of different methods of infant feeding. “The continued denial of the risks of not breastfeeding and the value of breastmilk supposedly to spare women’s feelings, is a patronising deception” (Palmer.G). Why is it that advertising formula is just business, but promoting breastfeeding is “pushy”? Mothers should have the opportunity to make an informed choice based on fact rather than anecdote. As parenting blog, An Unschooling Adventure has maintained: “Please mothers. Inform yourselves about the risks of formula. Stop blaming women who promote breastfeeding for trying to make you feel guilty, and target your anger towards the formula companies that have lied to you, or the health professionals that undermined your instincts.” While we’re on the topic of ‘choice’ – a highly cherished value of formula feeders – one burden of having choice is that one must be held accountable for one’s choice, a topic I discuss in length in my book ‘Breast Intentions’. If you feel guilty of your choice, that is your internal accountability system being triggered.

Argument: “Breastfeeders that drone on about the benefits of breastfeeding are smug, self-righteous and judgemental.”

Comeback: This is a straw-man argument. It is a misrepresentation of a breastfeeder’s position, created by the formula feeder for the express purposes of being knocked down. You see, everybody needs a victory or two for purposes of morale. If real ones are nowhere to be had, the formula feeder will wallop out a straw man.

In reality, the level of assumed smugness/judgeyness depends on the agenda of the person hearing the information not the person giving it. If someone finds criticism in statistics, I would suggest they are feeling defensive about their choices. Medics, the government, scientists and researchers have a duty to tell us what they know, and that is the obvious – that human mothers provide optimal nutrition for human babies. As parents don’t we have a duty to engage with such information?

Argument: “I really wish lactivists would stop implying that people who dont breastfeed do so because they think it’s less convenient or as some kind of lifestyle choice”.

Comeback: From the UK Department of Health Infant Feeding survey (which involves around 8000 mothers and is done every 5 years): “The most common reason for choosing to breastfeed was that breastfeeding was best for the baby’s health, followed by convenience. The most common reason for choosing to bottle-feed was that it allowed others to feed the baby, followed by a dislike of the “idea” of breastfeeding.”

Argument: “It’s none of your business how I feed my baby”.

Comeback: To see a whole catalogue of comebacks to this argument, click here.

Argument: “Formula and breastmilk are not THAT different”

Comeback: Are you sure? Click here.

Argument: “Of course formula is safe; They wouldn’t be allowed to sell it otherwise”.

Comeback: fireworks/cigarettes/stuff packed with e-numbers are sold every day. They are potentially dangerous, as is formula (see here).

Argument: “Well at least I won’t have breasts down to my ankles”.

Comeback: So-called ‘saggy’ breasts are a common consequence of pregnancy, not breastfeeding. During pregnancy, your breasts prepare for lactation, even if you have no intention of breastfeeding – and these changes are sometimes permanent. Excessive weight gain during pregnancy, hereditary factors, age or going bra-less can also result in breasts that are less than firm. Breastfeeding is blame-free.

Argument: “I stopped breastfeeding because I wanted more sleep.”

Comeback: Some women introduce formula hoping that if they do so their baby will ‘go longer between feeds’ or ‘sleep through’. Sometimes the first few formula feeds may bring that effect as the baby’s stomach is not accustomed to the tougher composition of the milk. Often the quantity of formula will need to be increased to maintain the effect. This can cause stomach stretching and lead to obesity in later childhood. In some cases, adding formula has no effect on the baby’s sleeping habits and for some it can lead to an upset stomach and greater night time disturbance (Moody et al). Breastfeeding mothers get more sleep and their sleep is of higher quality. A breastfed baby can eat as soon as he is hungry. If co sleeping, that means before the baby even starts to cry. A formula-fed baby has to wait for formula to be prepared and warmed, in the meantime getting more and more distressed and agitated as well as waking others in the household. When breastfeeding, even the mother does not need to wake up fully to nurse her baby. Furthermore, the hormones produced during nursing have a relaxing effect, and the mother is likely to sleep even better when she nurses her baby. Studies have shown that parents of infants who were breastfed in the evening and/or at night slept an average of 40-45 minutes more than parents of infants given formula (Doan et al). Parents of infants given formula at night had more sleep disturbance than parents of infants who were exclusively breast-fed at night. If you wanted more sleep, breastfeeding would have been the way to go.

Argument: “My boobs were too small to breastfeed”.

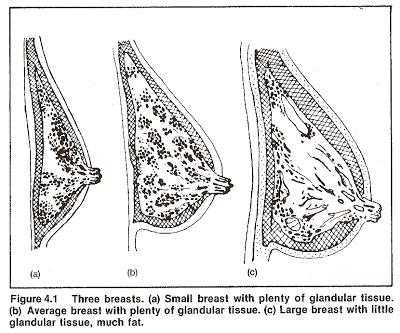

Comeback: Even if a woman is flat as a pancake her breasts will be able to do the job they were intended for. It is a myth that women with big breasts will be ‘better’ at breastfeeding. They may have more fatty tissue inside their breasts, but fat does not have a function as far as breastfeeding is concerned. Anatomically speaking, all lactating breasts perform in the same way. In no way does outward appearance affect the production of milk or a mother’s ability to dispense it.

Argument: “I couldn’t breastfeed because I was returning to work early”.

Comeback: A few weeks of breastfeeding are far better than none at all. Even breastfeeding for a few days has immense benefits. Colostrum provides not only perfect nutrition tailored to the needs of the individual newborn, but also large amounts of living cells which will defend the baby against many harmful agents. Furthermore with dedication and planning most mothers can work out a system for continuing to breastfeed even after they have returned to work.

Argument: “If you looked at a class of primary school children, you wouldn’t be able to tell which were breastfed or formula fed”.

Comeback: If I knew a little more about the children (any allergies, amount of doctors visits in the last 6 months, prevalence of ear infections, obesity, etc) I could make an intelligent guess using statistical likelihood.

Argument: “You have to eat a special diet when breastfeeding because breastmilk doesn’t contain all the vitamins that formula companies add to their milk”.

Comeback: As a breastfeeding mother, I do not need to eat any special foods, neither do I have to avoid certain foods. Unlike formula, all of the vitamins and minerals in my breastmilk are in a form that my baby can easily absorb. This means that even seemingly minute levels of vitamins and minerals in my breastmilk are bioavailable – able to be efficiently utilized by my baby. This is why breastfed babies have less frequent stools as they mature; they literally absorb more of their mother’s milk. Many of the highly concentrated ingredients in manufactured formula are simply excreted from a baby’s body as waste (Rubin. S). As for the assumption that I need a special diet, in the absence of a family history of food allergies, there is no benefit to eliminating foods from my diet.

Argument: “I didn’t breastfeed because I wanted my body back”.

Comeback: As Analytical Armadillo has pointed out, “instead of using breasts, we’ve moved on to hands (and bottles, sterilising, making up, cleaning) So more of a body part swap than actually getting anything back then?”

Argument: “You can’t diet and exercise when breastfeeding”.

Comeback: There is no reason why a healthy breastfeeding mother cannot consume a sensible calorie-controlled diet for weight loss. Mothers have breastfed successfully through history when food has not been plentiful. This is because a breastfeeding mother more effectively utilizes the food she ingests (Rubin. S). Furthermore, breastfeeding actually aids the process of weight loss. Over time, breastfeeding mothers tend to lose more weight than mothers who do not breastfeed. Moreover, sensible physical exercise does not harm the quality, quantity or taste of breastmilk. It is perfectly safe to breastfeed immediately after exercise, and regular exercise will not hinder my baby’s growth (Reuters).

Argument: “Breastfeeding means that you have little choice over what you can wear”.

Comeback: Breastfeeding does not require any specialised clothing. A breastfeeding mother may simply lift her top. A vest can be placed under her top to conceal her stomach if desired. Also wrap dresses, shirts and any top with buttons are other viable options. Formula feeding dictates a mother’s wardrobe to a greater extent than breastfeeding. As formula fed babies are more prone to posseting and reflux, their mother’s clothing needs to be changed more frequently.

Argument: “Breastfeeding didn’t work the first time so I’m not going to bother this time”.

Comeback: Even if you had trouble breastfeeding your first baby, research shows that you’ll likely produce more milk and have an easier time breastfeeding the second time around (Murkoff. H).

Argument: “Breastfeeding is only best for the baby if it is best for the mum” (otherwise known as: ‘Happy Mum – Happy Baby’).

Comeback: Babies are not automatically happy just because their mothers are which is what this equation implies. A mother who finds breastfeeding inconvenient and so switches to formula could become deliriously happy, and yet her baby, who may develop colic, allergies, and reoccurring illness as a consequence of the formula switch, would be far from happy. Also, look at it from a different angle: babies don’t get sad breastmilk when mum is struggling and happy breastmilk when breastfeeding is going well. There is even evidence that breastfed babies whose mums have PND don’t have changed EEG (brain wave scans) whereas bottle fed babies whose mums had PND did (they had the same EEGs as adults with depression) so if you do have depression giving up breastfeeding may not make baby happy (Jones. N et al). Furthermore, to state ‘Happy Mum – Happy Baby’ as some sort of ‘general truth’ is massively undermining and unkind to mothers who choose to continue breastfeeding in the face of pain, fatigue and anxiety. They may experience breastfeeding as not being ‘best’ for them at all yet continue because they want their baby to avoid disadvantage. Sometimes it’s hard for a mother to struggle through in the face of terrible adversity and have other mothers say that she should “give up” because of her physical and mental wellbeing. So whilst “Happy Mum – Happy Baby” sounds supportive and comforting, it is actually a disempowering, negative phrase. We should be empowering mothers to overcome their breastfeeding hurdles.

Argument: “Mothers are inundated with information about breastfeeding. There needs to be more information available about formula feeding”.

Comeback: Yes I agree. While there may be photos of rotten lungs on cigarette packets, and shocking pictures of alcohol-related car accidents on the TV, I’ve yet to see the risks of formula feeding being portrayed on the tins or TV adverts explaining what those risks actually are. I do think women should be informed – but when people say ‘women should have information about formula feeding’ they tend not to mean ‘risks of formula feeding’. No – this is not permitted. Because that makes women feel bad.

Your mother/mother in law:

Argument: “I couldn’t breastfeed so don’t be surprised if you can’t”.

Comeback: Luckily, failure isn’t inherited. I may have not had a positive breastfeeding example whilst growing up, but that has made me more determined to reclaim the breastfeeding tradition for the next generation.

Argument: “Is he feeding again?”

Comeback: It’s called demand feeding. It keeps my milk supply strong. Plus, because my breastmilk is so nutritious it is absorbed quickly. What would you prefer? The sounds of a baby happily slurping or the sounds of a baby unhappily crying?

Argument: “I noticed the baby didn’t have a dummy so I’ve bought one”.

Comeback: A dummy could cause my baby to confuse their sucking technique as dummies require a different type of sucking to breastfeeding. Also, a dummy would obscure my baby’s hunger cues and thus lead to less time spent at the breast. This will interfere with my establishing a solid milk supply. Moreover, babies who use dummies are more prone to oral thrush which could be transferred to my nipples and make them incredibly sore. Thanks, but we’ll pass on the dummy.

Argument: “Don’t let your baby fall asleep at the breast. You’ll make a rod for your back”

Comeback: It’s very normal and developmentally appropriate for babies to nurse to sleep. “For many babies at the height of exploration or distractibility, nighttime or naptime can often be the ONLY time the baby will nurse well. Allowing him to nurse at these times when he is more focused on nursing and less intent on other things helps ensures that he gets enough milk, that your supply is maintained” (Kellymom).

Argument: “But you’re depriving your husband of the chance to bond with the baby”

Comeback: Babies have a habit of hanging about the house for 20 or more years, so there is plenty of scope for paternal bliss. Besides there’s bathing, massaging, playing, reading to, singing to, babywearing and co sleeping which are far more efficient at enriching the parent-child bond than sticking a plastic bottle and silicone teat in the baby’s mouth.

Argument: “You’re preventing your child from gaining independence if you breastfeed for too long.”

Comeback: Children who breastfeed are generally more independent, and, perhaps more importantly, more secure in their independence. Forcing a child to stop breastfeeding before he is ready will not necessarily create a more confident child.

Argument: “It will be impossible to get into a routine”.

Comeback: Routine works when it emerges naturally. Schedule feeding is tough on babies whose digestive systems are not set on a four-hourly cycle from day one. A satisfied, contended baby is likely to be less demanding than one whose demands for food are routinely thwarted. A natural feeding pattern will emerge as my baby becomes more settled. (For evidence of greater insecurity as a result of strict sleep routines, see Higley.E and Dozier. M; for evidence of greater irritability and fussiness as a result of routines, see St James-Roberts et al).

Argument: “You should stop breastfeeding now that your baby has teeth”.

Comeback: “When a baby is latched on to the breast correctly, his lips are flanged and his gums land far back on the areola (the dark area around the nipple). His bottom teeth are covered by his tongue and do not come in contact with the mother’s areola at all. For this reason, a baby who is latched on correctly and actively nursing cannot bite” (La Leche League).

Argument: “Once they can talk, they are too old to breastfeed”.

Comeback: There is no evidence to suggest that breastfeeding beyond an arbitrarily determined point is dangerous and unnatural. In our culture we project our own sex and gender hangups on to the child. However the reality is that the emotional and physical benefits of breastfeeding do not diminish as a baby becomes a toddler or preschooler. The World Health Organization and UNICEF strongly encourage breastfeeding through toddlerhood. My milk is still providing my child with essential proteins, nutrients antibodies and other protective substances and will continue to do so for as long as I continue nursing. Some of the immune factors in breastmilk even increase in concentration during the second year (Goldman. A et al). In fact, human biology is geared to a weaning age of between 2 1/2 and 7 years (Dettwyler. K). Also, extensive research on the relationship between cognitive achievement (IQ scores, grades in school) and breastfeeding has shown the greatest gains for those children breastfed the longest (van den Bogaard, C. et al). Furthermore, the reassurance that breastfeeding provides to a child may be more important than ever as my child begins to explore the world and tackle new developmental milestones. Extended breastfeeding serves to lessen temper tantrums and helps a child to quickly fall asleep at naptime. The consistency of the breastfeeding relationship can serve as a stabilizing force within the child’s life.

Argument: “He’s crying because you’re starving him”

Comeback: To quote Dr Benjamin Spock, “Hunger is not the most common reason for crying”.

Health care professionals:

Argument: “It’s good that you’re going to try to breastfeed, but bear in mind that many women can’t”.

Comeback: In many less-developed societies, the idea of being unable to breastfeed does not exist.

Argument: “I want to know exactly how often baby feeds and for how long at each breast”.

Comeback: Asking a woman in rural Africa how often she breastfeeds is like asking someone with an itchy rash how often they scratch. I’d rather not turn something natural into something regimented.

Argument: “I think you ought to top up with formula to give yourself a break”.

Comeback: What, and ruin my baby’s virgin gut (see here) as well as sabotaging my milk supply? No thanks. Besides, how is sterilising bottles and teats, boiling kettles, mixing formula and waiting for it to cool ‘giving myself a break?’

Argument: “Your supply is low so you need to top up with formula”.

Comeback: If my baby’s hunger and thirst are satisfied by other fluids, he will want to suckle less at the breast. This is likely to make my milk supply even worse. If there is a problem with my baby not getting enough milk, pumped breastmilk is a better alternative to formula. Besides, what has makes you think that my supply is low? If you can prove that there truly is a supply problem can you refer me to a reputable lactation specialist and also supply me with a supplemental feeding system? (Direct your health professional to this article: ‘Look at the Baby, Not the Scale’).

Argument: “One bottle of formula won’t do any harm”

Comeback: (Again, explain to her what the virgin gut is).

Argument: “There’s no such thing as nipple confusion”.

Comeback: To get milk from the breast, baby must coordinate tongue and jaw movements in a sucking motion that’s unique to breastfeeding. On the otherhand, thanks to gravity, milk flows from a bottle so easily that baby does not have to suck “correctly” to get milk. As hungry babies will take whatever is easiest to fill their tummies, if a flowing bottle that does the chugging for them is offered, many will decide that they don’t want to work for their dinner after all. Hence why it’s so important to not allow hospital’s to push bottle supplement feeding on newborn babies- who are especially vulnerable as they haven’t learned how to latch and feed from the breast yet (Informed Parenting). (Direct the health professional to my article here which explains how bottles and dummies can sabotage breastfeeding).

Argument: “There’s no nutritional value in breastfeeding past 6 months”.

Comeback: After six months, breastmilk still contains protein, fat, and other nutritionally vital components. Breastmilk still contains immunologic factors that help protect the baby. In fact, some immune factors in breastmilk that protect the baby against infection increase as the child gets older. If my baby becomes unwell, breastmilk is easily digested and nourishing. Also if my baby becomes a fussy eater, my breastmilk will make an important contribution to his restricted diet – it may become his only decent source of vitamins! As babies cannot digest cow’s milk, if I were to stop breastfeeding now I would have to switch to formula at least until my baby is a year old. Why would I want to have the extra cost and hassle of that?

Argument: “There’s not enough iron in breastmilk”.

Comeback: Iron stores are laid down during pregnancy and are enough to last my baby until he is six months old, when complimentary solids can be introduced (Lim. P). Although the iron content of breastmilk is small, it is absorbed more efficiently because it is helped by the natural form of vitamin C also present in breastmilk. Breastfed babies absorb nearly 50 percent or the iron in breastmilk whereas formula fed babies absorb only about 10 percent of available iron from formula (Rubin. S). Furthermore, unnecessary iron supplementation can lead to diarrhoea and adversely affect a baby’s growth. This is because it stops lactoferrin from being effective as it cannot be ‘mopped up’ and so can be used by the harmful bacteria in the gut to grow and reproduce. This has happened with formula (see the articles in Reuters and Bloomberg).

Argument: “You need to introduce solid foods before 6 months because your baby’s growth has slowed down”.

Comeback: It has been noted that, “by the time they are ready for solids breastfed babies are often gaining less than many of the growth charts say they should” (Lim. P). Up until 6 months breastfeeding provides my baby with a perfect balance of easily digestible proteins, fats and vitamins. If I were to begin feeding my baby solids too early the food would displace a certain volume of nutrient-dense breastmilk from my baby’s diet. Feeding my baby solid food early will not increase my baby’s overall growth. (Direct the health professional to this Le Leche League factsheet).

Argument: “Let’s pump to see how much milk you’re making.”

Comeback: A breastpump cannot be used to gauge the effectiveness of my milk supply. Most mothers do not let down well with the breastpump – it is hard, cold and mechanical, and will give me none of the stimulus that my warm, living baby does. Commonly a mum will spend 30 minutes attached to a breastpump and obtain a measly 3oz for her troubles. Babies obtain much more.

Argument: “You’ve got inverted nipples so you will need to use a nipple shield if you insist on breastfeeding”.

Comeback: Babies do not breastfeed on nipples, they breastfeed on the breast. The shape of my nipples is not important. As far as my baby is concerned, it is highly unlikely that she will ever meet or feed from another pair of breasts and, to her, my breasts are just perfect. Once feeding well, my baby’s sucking action can and will draw out flat and inverted nipples. If I use nipple shields, my baby may not able to compress my areola properly, which can lead to long-term milk production problems and increased nipple soreness and damage (Direct the health professional to this article).

Argument: “Breastfeeding twins will be too difficult to manage. Here’s some formula”.

Comeback: Breastfeeding twins is easier than bottle feeding twins. A mother will require four hands to bottlefeed twins simultaneously. Not so with breastfeeding. Also, because twins tend to be born prematurely, they especially benefit from the nutritional composition of breastmilk.

Argument: “Premature babies need to learn to take bottles before they can start breastfeeding”.

Comeback: Premature babies are less stressed by breastfeeding than by bottle feeding. In fact, weight or gestational age do not matter as much as the baby’s readiness to suck, as determined by his making sucking movements. There is no more reason to give bottles to premature babies than to full term babies. When supplementation is truly required there are ways to supplement without using artificial nipples.

Ignorant members of the public:

Argument: “You shouldn’t breastfeed in public; you may offend men or arouse them.”

Comeback: Many men are simply curious about female breasts and breastfeeding since society has made it a taboo. It is well known that if you make a taboo available and expose it, then it gradually loses its attractiveness. At a certain time woman’s ankle was a fetish – today men are not turned on by seeing women’s ankles. Covering up makes it ‘something forbidden’, which produces feelings of curiosity (Female Intelligence Agency). Besides, men are not primitive animals who become overcome with lust at the sight of women’s skin, no matter what FHM and Nuts may suggest. Such assumptions are an affront to men.

Argument: “You shouldn’t do that in public; children could see.”

Comeback: Yes children could see. When they go to a zoo, or a farm, or have pets in their homes should their parents make sure they never see animals nursing to avoid scarring them? Mammals nurse their young. Humans are mammals. “Nursing in public is one of the best things a breastfeeding mother can do for society as a whole – not just to give her own child a healthy start, but to give other people’s children the opportunity to see mothering and nurturance at the breast as normal, healthy, and enjoyable” (Nursing Freedom).

Argument: “Breastfeeding mothers are exhibitionists; why can’t they just feed their baby before they leave home?”

Comeback: Contrary to what trash Gina Ford makes her living spouting, babies are not aware of the clock. They cannot time their hunger around the convenience of their parents.

Argument: “OK well why can’t they just pump milk and give it in a bottle whilst they’re in public?”

Comeback: Expressing breastmilk is tedious and can reduce supply as well as risking nipple confusion. Also some mothers who have perfectly good breastmilk supplies cannot express much milk, even with the most modern of breastpumps.

Argument: “Yes, breastfeeding is a natural bodily function vital for survival. So is taking a dump. But we don’t rant on about people’s right to do THAT in public.”

Comeback: The fantastic Analytical Armadillo has fashioned an appropriate response here.

Argument: “After a certain point, the breastfeeding relationship is more for the mother than the child.”

Comeback: There’s no denying that breastfeeding provides emotional and physical benefits to a mother as well as a child. To continue to nurse an older baby and hate it tends to become martyrdom – a poor basis for any family relationship (Bumgarner. N). Besides, if there weren’t anything in the relationship for the child (comfort, nourishment), he simply wouldn’t nurse (La Leche League).

Argument: “If you breastfeed for too long, you will give your child breast fixation issues”.

Comeback: There is no evidence whatsoever to suggest that children who are breastfed for extended periods develop Oedipus complexes, become gay or develop an abnormal fixation with breasts. If that were the case, then a huge proportion of the world’s population would fall into these categories, thereby redefining the parameters of ‘normal’ (Mothers Over 40).

Thus concludes my whistle-stop tour of infant feeding warfare. I hope I have covered the most prevalent arguments that persistently crop up in the life of the breastfeeding mother.