Charles Darwin (and your mum) would suggest that, as a human, you are a clever, resourceful, creative creature. Indeed, there is much truth in this. Over the centuries we humans have used our growing awareness of actions and their consequences to double our life expectancy, discover electricity, flight, artificial intelligence, nano-technology, and even space flight. However when it comes to feeding our infants, there linger striking parallels between the way we do it now, and the way we did it centuries ago. What follows is an eclectic collection of examples illustrating how, in negative ways, we are perpetually stuck in our ways, failing to learn from previous mistakes.

Quitting breastfeeding

The past:

In the past, failure to breastfed usually necessitated the services of a wet nurse. Breastfeeding failure was sometimes a result of tight corseting, however self-interest was quoted as the main reason for sending babies to wet nurses. Here is a portrait commissioned by Henry VI of France (1573-99) of his mistress Gabrielle d’Estrees with her wet nurse.

The present:

Self-interest is still quoted as the prime reason for not breastfeeding. From the UK Department of Health Infant Feeding survey (which involves around 8000 mothers and is conducted every 5 years): “The most common reason for choosing to breastfeed was that breastfeeding was best for the baby’s health, followed by convenience. The most common reason for choosing to bottle-feed was that it allowed others to feed the baby, followed by a dislike of the “idea” of breastfeeding.”

Sex and breastfeeding

The past:

Self-interest for giving up breastfeeding was sometimes on behalf of the father who wanted to resume sexual relations with his wife as soon as possible. A common misconception was that “carnal copulation troubleth the blood, and so by consequence the milk” (i.e. somehow shagging would corrupt a mother’s milk).

The present:

Today, misconceptions that breastfeeding interferes with sexual relations abound in popular ‘parenting bibles’. Some quotes for you to cringe at:

“The main advantage to giving up breastfeeding is that once milk production ceases the dad’s access to said breasts will no longer be denied” (Fatherhood: The Truth).

“The decision to breastfeed should be somewhat mutual. I have several friends who say that their partners were turned off by the sight of them feeding the baby. Before the baby is born, you should allow your partner to share his feelings about your suckling someone other than him. Consider whether you feel comfortable with the notion of turning your lovely sex toys into udders for the next few months and whether your partner feels at least a little comfortable with that idea too” (The Best Friends’ Guide to Surviving the First Year of Motherhood).

“In its aftermath, breastfeeding makes your tits look like bananas in a Waitrose bag, and while you’re doing it, it interferes with sex” (Bring It On Baby).

Breastfeeding substitutes:

The past:

For the mother that quit breastfeeding, if no wet nurse was available, the safest feeding option for newborns was believed to be suckling an animal. Here’s some assess feeding babies:

And a nanny goat in action:

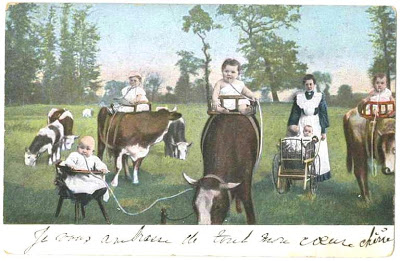

Babies feeding directly from cows:

The present:

For the mother that quits breastfeeding, her baby is still given the milk of another species – infant formula, aka reconstituted cow’s milk.

Undermining breastfeeding

The past:

For those that attempted to nurse their babies, many mothers would quit as a result of being ubiquitously undermined. Often they were discouraged due to the fear that their milk must be inadequate. An even more insidious doubt entered mothers’ heads when it was suggested that their milk might appear plentiful, but have no nutritional value.

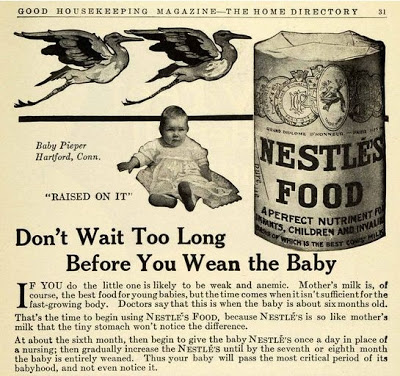

Take a gander at this advertisement from Nestle. Published in 1911, it’s typical of the attitude that at 6 months breast milk is inferior and should be replaced by commercial formula:

The present:

“There is no nutritional value in breastmilk after 6 months” is a popular mantra of misinformed health professionals. Many mothers needlessly switch from breast to ‘follow-on’ formula at this point. However the World Health Organisation has declared follow-on formula as ‘unnecessary’.

Inverted nipples

The past:

Aside from fears that their milk was inadequate, mothers of the past also had to contend with the worry that their breasts were ill-designed. For women who were deemed to be “deficient of nipple” an advised solution was to wrap a woollen thread two or three times around the base of the nipple and pull moderately tightly to encourage the nipple to “sufficient prominence” (A Treatise on the Diseases of Married Females by John C. Peters 1854). – It was written by a bloke you say, no shit!

Another popular cure for inverted nipples was to scoop out two large nutmegs, then put them in brandy for a week, and afterwards dry them. The breasts were then to be rubbed every morning with glycerine, and the nipples washed over with brandy, and, when dry, the nutmegs were to be placed one on each nipple. This apparently, “drew them out and hardened them” (Warren. E. How I managed My Children From Infancy to Marriage. 1865). – Another bloke.

The present:

Nowadays a mother concerned about her nipples is often advised to use a device probably invented for use in Game of Thrones: nipple shields. They are artificial nipples worn over the mother’s nipple during breastfeeding. Modern nipple shields are made of soft, thin, flexible silicone and have holes at the end of the nipple section to allow the breast milk to pass through. However when using nipple shields the baby may not be able to compress the mother’s areola properly, which can lead to long-term milk production problems and increased nipple soreness and damage.

Doctors alliance with formula

The past:

From their conception, formula companies realised that an alliance with an influential body like medical professionals would be profitable. Initially doctors objected to formula because its commercialisation removed infant feeding from the doctor’s domain, which resulted in a loss of income to the doctor. To tackle this, in the early eighteenth century, formula companies sought to seduce doctors by launching advertising campaigns in medical journals. The companies agreed that formula packaging would instruct the mother to consult her doctor before using the product, thus bringing control of infant feeding under the direction of the medical profession. Here (left) is an ad for Nestle’s infant food in the Journal of the American Medical Association, 1896.

The present:

Modern-day midwives, health visitors, GPs and other health professionals are persistently subject to very clever and insidious marketing from formula companies via advertising, gifts, conferences and ‘training days’. In November 2008 formula company Aptamil paid the British Journal of Midwifery to include a calendar branded on every page with the Aptamil name and claims about the infant formula. Advertising in medical magazines and periodicals is a common formula company tactic which has endured to this day (read more about the targeting of health workers here).

Dangers of formula

The past:

As a consequence of the increase in artificial feeding, infant mortality made a sharp rise. Aside from the risk of death, formula fed babies were prone to respiratory illnesses and bacterial infections.

The present:

A study entitled ‘Breast Feeding And the Risk of Post Neonatal Death in the United States’ has found that formula fed infants have a 56% higher death rate than breast fed infants (Pediatrics. 2004 May;113(5):e435-9). Furthermore, formula fed babies continue to be more prone to respiratory illnesses and bacterial infections alongside a host of other chronic ailments.

Formula company misconduct:

The past:

Further dangers were exposed in 1939 when Nestlé was exporting condensed milk to Singapore and Malaysia as ‘ideal for delicate infants’, though it was banned in the UK for causing rickets and blindness. In a speech Dr Cecily Williams said, ‘Misguided propaganda on infant feeding should be punished as the most miserable form of sedition; these deaths should be regarded as murder.’

The present:

The present:

International regulations forbid providing samples of infant formula to new mothers, but in the Philippines, Nestlé has recently been exposed for hiring graduate nurses as ‘health educators’ to visit mothers at home and try to convince them to use their products.

Anti-breastfeeding propaganda

The past:

Despite the dangers of formula, outspoken anti-breastfeeding advocates maintained: “Let no mother condemn herself to be a common or ordinary ‘cow’ unless she has a real desire to nurse. I myself know of no greater misery than nursing a child” (Jane Ellen Panton, The Way They Should Go. 1896).

The present:

Parenting guides containing anti-breastfeeding propaganda litter library and bookshop shelves across the globe (I expose a few examples here). Even popular parenting magazines, along with their formula advertisements, have an openly anti-breastfeeding agenda. Recently the editor of Mother and Baby Magazine described breastfeeding as “creepy” (see the article in The Guardian).

Breastfeeding management

The past:

For those mothers that continued to nurse, strict self-care was advised, including a cold, salt-water shower or bath every morning. They were advised against “excessive novel-reading” and to “avoid all over-heating from running, dancing, excessive fatigue, etc; likewise the indulgence of violent passions and emotions”. It was believed that the child might have convulsions if fed after such excesses (Child. L. The Mother’s Book. 1831). Childcare ‘experts’ of the time, including Dr Eric Pritchard insisted that “Lactation is far more likely to go wrong in a woman than in the teetotal, vegetarian, nerveless cow” (Pritchard. E. Infant Education. 1907). He maintained that in order to breastfeed successfully women had to make themselves as much like cows as possible. They were to drop all social commitments, rest a lot and follow a bland diet.

The present:

Misinformed health professionals and formula company ‘carelines’ advise that women carefully monitor their diet (Aptamil prescribe a diet for breastfeeding mums here; as do SMA here), wash their hands before every breastfeed (as per SMA’s instructions), abstain from alcohol consumption, and even avoid strenuous exercise for fear that it will turn breastmilk ‘sour’.

Feeding routines

The past:

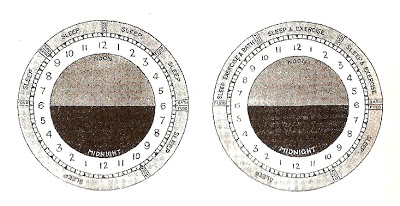

Another unnecessary burden to the breastfeeding mother was the advent of the regimented routine. Baby had to be fed by the clock, not by natural intuition. Not when he thought he needed food, but when his mother thought he needed food because her doctor told her so. “From the first moment the infant is applied to the breast, it must be nursed upon a certain plan” (Bull. T. Maternal Management of Children in Health and Disease. 1877). After a mere week of demand feeding it was insisted that: “It is essentially necessary to nurse the infant at regular intervals of three and four hours”. The prescribed routine included “eight hours unbroken sleep at night” (see illustration below). In 1896, a book called The Care and Feeding of Infants it was maintained that too much handling, cuddling etc would weakened the child.

The present:

Today the regimented routine has made a comeback in the form of Fishwife Gina Ford’s orderly timetable for ‘contented’ babies. Ford’s instructions for breastfeeding a four-week-old are draconian: up by 7am, feed to be finished by 7.45am, nap in his room at 8.45am, woken an hour later, 25 minutes at the breast (fed always in the nursery) at 10am, play on his mat at 10.30am, in bed by 11.45am, awake again by 2pm, feed now but must be over by 3.15pm, walk at 4pm, next feed to be over by 5pm, bath at 5.45pm, feeding by 6.15pm (during which parents should not make eye contact with their child in order not to excite it before bedtime), and “fully swaddled and in the dark, with the door shut, no later than 7pm”.

Thickening feeds

The past:

To encourage babies to adhere to strict feeding routines, some mothers used flour or cereal mixed with broth or water to thicken up babies’ feeds. It was hoped that the difficulty of digesting such a stodgy concoction would make babies sleep longer between feeds.

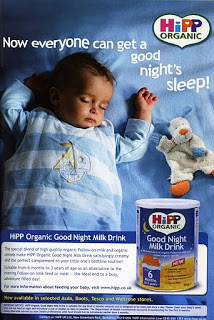

The present:

The present:

Nowadays ‘Goodnight Milks’ are thickened with cereals to make them harder to digest. Aside from the risk that they will be used to replace a night time breastfeed, another worry is that the products could encourage parents to put their baby to bed immediately after bottle-feeding which would rot a baby’s developing teeth. There is also a risk that busy mothers may consider the product suitable for ‘settling’ their baby during the day and use them more often, or even use them for infants under six months.

Public modesty

The past:

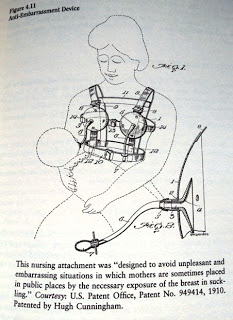

Another facet of so-called ‘breastfeeding management’ was the preservation of mothers’ modesty in order to protect public sensibilities. To conceal breastfeeding from public view the sadistic-looking “anti-embarrassment device” was marketed in 1910. This was a massive harness which cupped the breasts and provided rubber-tube extensions for the nipple, ending with a rubber teat by which the baby could be fed in public places “avoiding the necessary of exposing the person”. If you weren’t using artificial milk, you could at least appear to be doing so.

The present:

Nowadays we have ‘fetching’ nursing covers to conceal the fact that we are breastfeeding. They come with even more fetching brand names, such as ‘Udder Covers’ and ‘Hooter Hiders’. To save me the trouble, a fellow parenting blog has listed the ways in which such nursing covers do breastfeeding a disservice (see here).

Measuring intake

The past:

Along with adhering to strict routine, mothers were also expected to appease society’s growing obsession with order and certainty. By the 1850s baby food manufacturing was considered to be vastly improved, and because artificial feeding enabled parents and their doctors to gage a baby’s intake, parenting guides recommended formula without hesitation. The esteem doctors afforded to artificial feeds, combined with exaggeration of the difficulties of breastfeeding contributed to mothers rejecting the uncertainties of suckling in favour of the perceived security of the bottle. Formula was calculated to the last calorie, was measurable and was very much a scientific process. Breastfeeding was not viewed as sterile nor was it the least bit scientific. It was not seen as measurable.

The present:

The preoccupation with certainty and measurable intake continues to the present day. Mothers feel more secure bottle feeding because it enables them to see the baby’s intake in ounces. Health professionals reinforce this insecurity by their preoccupation with weight charts, advising measurable formula top-ups, test weighing, and using breastpumps to measure supply. All of which undermine the breastfeeding relationship.

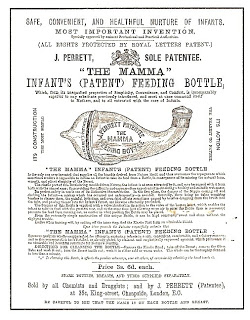

Bottle design

The past:

It became apparent that although bottles were fantastic at measuring a infant’s intake, some babies rejected their cold, hard, subhuman form. Consequently bottle designs were re-modified. The most popular new design was a slightly concave glass bottle intended to resemble a breast “to practice a useful deception on the child, inducing the child to think that it derives nourishment directly from its mother”. On the nipple site was a soft teat of deerskin, stuffed with a sponge to control milk flow. In order to perfect the deception, a flesh-coloured elasticated pad was available to fit over the bottle.

The present:

Tomee Tipee ‘Closer to Nature’, Medela Calma, and Mimijumi bottles claim to resemble the human breast. However their teats don’t flex in the mouth the way a human breast does. These, and other bottles designed to mimic human breasts, are simply domes with longer tube-like nipples attached. When a baby breastfeeds, it takes the areola into its mouth, not just the nipple. If used within the breastfeeding relationship, bottles can lead to a young baby preferring the faster flow of milk. Also the different technique used for sucking a bottle teat can cause babies to have difficulty latching-on and sucking at the breast, which will in turn interfere with the mother’s milk supply. Eventually baby may refuse the breast altogether.

Bottle propping

The past:

Along with bottles that resembled human breasts, self-feeding bottles were also popular. Babies were often left lying on the floor to suck milk or whey through a long tube attached to a glass bottle whenever they were hungry (see right illustration). Another type of self-feeding bottle had short legs at the base to stand up on the baby’s chest at a suitable incline. Another hung around the neck on a ribbon. One patient in 1897 recorded that “in the rising of infants sustained by the bottle it becomes a source of great inconvenience and labour to provide food at varying intervals, especially at night, when rest and recuperation are necessary”. It described a bottle with a groove around the middle, so that it could be suspended by a pulley from the ceiling over the baby’s cot, nipple-end up, to prevent drips. All the baby had to do was yank it down and drink to its heart’s content.

The present:

Soothing guilt

The past:

Childcare writers bent over backwards to reassure mothers who “couldn’t” breastfeed, and in doing so, they effectively demoralized those who could. A popular childcare guide (Your Child’s Mind and Body, by Flanders Dunbar, 1949) maintained that: “Most young mothers wonder whether or not they should nurse their babies. You do not have to nurse your child. Scientific evidence indicates that children who have never been nursed as just as healthy, sometimes more healthy, both physically and emotionally, as children who nursed. If you want to nurse your child, by all means do so, but allow your doctor to suggest from the very beginning additions to his breast diet such as orange juice, extra formula, or cereal. If you are reluctant to nurse your child, if it makes you tense or uncomfortable, or if you are too busy and are just doing it because you have an idea that it is your duty, do not attempt it”.

The present:

The present:Appeasing mothers who don’t breastfeed continues to be the folly of many childcare authors. Marcus Berkmann (Fatherhood: The Truth, 2005) claims with faux confidence that “bottle feeding is never going to do anyone any harm”; While Vicki Iovine (The Best Friends Guide to Surviving the First Year of Motherhood, 1999) concurs: “As our own mothers will quickly point out, our entire generation is a testament to the fact that formula-fed babies can survive and even prosper”. In her childcare guide aimed at new parents (Babies for Beginners: Keeping Your Baby Happy and Healthy, 2009) Roni Jay reassured that “You can’t tell looking at a child or even an adult whether they were breast or bottle fed. It doesn’t show in their looks, their personality, or their health, so how can it possibly be that important. Answer: it can’t”. No stone is left uncovered in an attempt to lick the wounds of the non-breastfeeding mother; from diminishing the health benefits of breastfeeding: “The NHS is over promoting the advantages of breastfeeding” (Eleanor Birne, When Will I sleep Through the Night? An A-Z of Babyhood, 2011), to championing the imagined culinary delights of formula: “Formula looks nicer; it would surprise me in no way if it didn’t also taste nicer” (Bring it on Baby: How to have a Dudelike Pregnancy. ZoeWilliams 2010).