(Following on from Part One and Part Two)

Topsy and Tim and the New Baby (Contemporary Edition: 2009)

Jean Adamson and Belinda Worsley

Topsy and Tim are twins that have been entertaining and sympathising with young children since 1960. Their books revolve around “first experiences” or should I say, ordeals, that young children commonly deal with: going to the dentist, visiting the doctor, having their eyes tested, being sent to hospital, starting school, moving house, losing a pet, catching nits, being dragged around the supermarket by Mum. This book adds to the array of crap that parents put their children through by exploring what happens when a new baby arrives. However for once Topsy and Tim are spared. Rather than spoil the cosy twosome, the authors inflict a new baby on their poor friend Tony. I say poor, because new babies are often resented in children’s books and this one is no exception. The book begins predictably with the pregnant woman putting baby clothes into drawers looking as smug as, well, a pregnant woman. Then the baby comes along and “he cries a lot”. Has he pooed his pants, enquires one of the children. No he wants a feed; and then we see a sincerely beautiful full-page illustration of the baby being nursed by a beaming Mum. Yes she appears to be in her dressing gown but at least her hair looks presentable and her teeth have definitely been brushed to perfection. The kids have a drink too (from the fridge), they play in the garden and then they watch the baby having its nappy changed. For the most part, babycare is portrayed in a positive non-burdensome light expect from the occasional sibling-related spat.

The vintage edition of this book also features the endearing breastfeeding scene, albeit a less detailed version:

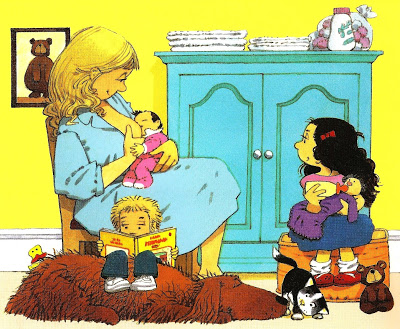

Usborne The New Baby

Anna Civardi and Stephen Cartwright

This popular book is pretty much the same recipe to ‘All You Need to Know About Babies’ (reviewed in Part One), only minus the sex and the camcorder. The illustrations are charming, as you’d expect from Usborne, and there’s the infamous rubber duck to spot on each page. At the hospital there’s a pink or blue bow tied to each crib to signify the gender of the contents. Being the hormonal sap that I am, I found this endearing (may feminism strike me down). Feeding is only shown once, but it is explained that the baby “will need to be fed many times each day”. Mum is shown breastfeeding whilst her young daughter pretends to feed a doll with a bottle. The authors missed a treat there! It’s been well documented that when their mothers breastfeed, older children often copy by placing a toy on their own breast. I hope to see this represented in children’s literature one day.

Usborne The New Baby Sticker Book

Anna Civardi and Stephen Cartwright

A virtual replica of the above book, except this one also contains a large pull-out sheet of stickers. The stickers are designed to replace words in the book. So we have: cot, scales, nurse, bag, baby, towel, etc. There’s a sticker for ‘bottle’ but not for ‘breast’; presumably because while breastfeeding is shown via illustration, it is not mentioned in the text.

New Born

Kathy Henderson and Caroline Binch

This book describes the tactile sensations that inundate a newborn during his introduction to life outside the womb. For instance, the shadows of his own flaying hands, a door slam, the flickering picture of the TV, the rustling of paper, the glow of a light bulb. The vivid watercolour illustrations are generous on colour and equally liberal on realism. The newborn actually looks like a newborn, very Winston Churchill, with oversized babygro, wrinkled feet, squashed nose, furrowed brow and persistently bewildered expression. Family life is portrayed affectionately and convincingly with charming imperfections. The text is tender, richly descriptive and effectively transports the reader into the newborn’s unique perspective. Unlike the majority of books in the ‘new baby’ genre, the siblings in this book appear to cherish the new arrival with curiosity, pride and unreserved affection. Each child is shown cradling the newborn and gazing adoringly at him. Curiously, breastfeeding does not feature until the back cover, a great shame as the act of nursing lends itself to the sort of rich, intense description that adorns the pages of this book.

Rosie’s Babies

Martin Waddell, illustrated by Penny Dale

An award winning book, Rosie’s Babies looks at sibling jealousy in an endearing and convincing way. When her mum has a new baby, Rosie conjures up a few babies of her own, represented by her toys. Then she invents stories about their mishaps. The book focuses on dialogue between Rosie and her mum. Whilst her mum carries out various babycare tasks, in an effort to glean her attention Rosie tells her all about her own ‘babies’ and their adventures. In politically correct fashion, Rosie is viewed bottle feeding her toys, despite living in a ‘breastfeeding household’. The layout of the book is novel, with the conversation between Rosie and her Mum illustrated on the left page, and Rosie’s fantastical stories depicted on the right. We see Rosie’s babies falling down a snow-laden hill, driving lorries and speedboats, visiting parks at midnight, baking cakes, and other random fantasies. When Mum has finally put the baby sibling to bed, Rosie decides that she doesn’t want to talk about her babies anymore; she wants to talk about HER. What a diva.

The Last Puppy

Frank Asch

The Last Puppy is a simple short story about a complex issue: feeling inadequate. It is told in first person narrative from the perspective of one of a litter of puppies. The story begins with the puppy explaining that he was the last to be born. This is accompanied by a charming illustration of a mother dog giving birth to her litter. Yes there’s no blood to be seen but at least a hint of realism is evident as the puppy descends from her stretched vagina. The text continues, informing us that he was the last puppy to “eat from Momma” (cue gorgeous illustration of the puppies lined up nursing), the last to learn to drink from a saucer and the last into the kennel at night. When the puppy’s owner erected a ‘puppies for sale’ sign, the puppy feared he would be last again. Sure enough all his siblings were sold one by one and he remained the last puppy. I won’t spoil the climax. Suffice to say it will put a smile on your face and warm fuzzies in your heart. I have a soft spot for this book and will be sad to return it to the library. The minimal illustrations are reminiscent of Dick Bruna’s Miffy – an 80s favourite. The repetition of the text is enjoyable for young children as well as serving to build up the reader’s desire for a resolution of the story’s problem.

Where Did I Come From?

Peter Mayle

Let me say off the cuff – this book is porno for children. I’m not a prude in any respect but I question the explicitness of this text, particularly when one considers the target audience. Does a seven year old really need to know what an orgasm feels like? Or the texture of semen? I’m all for dispelling stork and cabbage patch myths, but surely this should be done in an age-appropriate manner? The text goes into unnecessary detail and I was cringing throughout. Evidently I won’t be using this book for my own children, which is a shame because it does have a glorious pro-breastfeeding stance. The book begins with a look at the naked human body. When describing breasts (or ‘bosoms’, ‘titties’ or ‘boobs’) the text explains: “When you were just born, your mother’s breasts were rather like a mobile milk bar. For the first few months of your life, the only food you could eat was milk. Well, the milk that kept you alive for those first few months either came from a bottle or your mother’s breasts. So it’s a quick thank you to breasts before we move on”. This text is accompanied by an illustration of a mother breastfeeding, both breasts and nipples visible, with the caption: “Aaah. Milk, wonderful milk”. Then the text explains what hips, penis and vagina are for. So far, so good. It’s the graphic descriptions of sexual intercourse when the uncomfortable mist descends. “The man pushes his penis up and down inside the woman’s vagina, so that both the tickly parts are being rubbed against each other. It’s like scratching an itch, but a lot nicer. This usually gets quicker and quicker as the tickly feeling gets stronger”. Just when you think the author really ought to stop there, he continues: “Something really wonderful happens which puts an end to the tickly feeling. When the man and woman have been wriggling so hard you think they’re both going to pop, they nearly do just that. All the rubbing up and down that’s been going on ends in a tremendous big lovely shiver”. The author then likens an orgasm to a really big sneeze, but he’s not finished yet. The text continues: “At the same time, a spurt of quite thick, sticky stuff comes from the end of the man’s penis and this goes into the woman’s vagina”. The sperm are illustrated in typical comic form: as Casanovas, rose between their teeth. Then you get the bog-standard textbook description of sperm meets egg, baby grows bigger each month, mum gives birth. If you want a no-nonsense children’s book about baby-making, I suggest you purchase “See How You Grow” (reviewed later, in Part Five). It’s equally liberal sans the sleeze.

The Red Woollen Blanket

Bob Graham

No prizes for guessing what this book is about. The Red Woollen Blanket tells the tender and sympathetic story of a girl called Julia and her relationship with her comfort blanket. The blanket starts life as a gift given to Julia’s pregnant mother. When Julia is born she is swaddled in it whilst breastfeeding, she sleeps with it, sucks it, chews it, you get the score. As Julia grows, she crawls with it, toddles with it, walks with it, and so on. The story is as much about the lifecycle of Julia as it is about the lifecycle of the blanket. Many parents will appreciate that comfort items can have a life expectancy of many years, and Julia’s red blanket is no exception. It braves all seasons, it endures the lawnmoor, it survives the dog. By the time Julia is school-aged the blanket is no bigger than a postage stamp, and this is when she looses it – or rather it is nicked by a fellow pupil. The text doesn’t mention the thieving but it can clearly be seen from the illustrations. On the topic of illustrations, Bob Graham perfectly captures the tender yet chaotic life of a young family. Hair is unbrushed, the parents look exhausted, and in the home possessions can be seen sprawled across the floor. Unfortunately, as with Bob’s other title ‘Brand New Baby’ (reviewed in Part One), a messy household is apparently incomplete without some dummies and bottles lying around. Also, as with Brand New Baby, breastfeeding duration does not seem to extend out of the hospital realm. However despite these disappointments, what pleased me about this book, aside from the initial boobage, was the stealthily unexpected happy ending. Despite her treasured comfort blanket going astray (at this point the heartbeat of every parent reading grinds to a halt) surprisingly Julia doesn’t care. She “hardly missed it”, which is a comforting conclusion for children and parents alike.

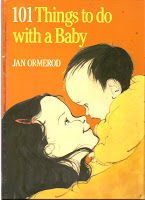

101 Things to do with a Baby

Jan Omerod

This book showcases examples of how a family can integrate a new baby into their routine. The book is titled “101 Things to do with a Baby”, but sadly breastfeeding isn’t one of them. Instead breastfeeding is shown only on the cover insert – and the nursing mother looks absolutely knackered with sunken eyes and unbrushed hair. The image seems out of sync with the rest of the book’s illustrations which are lively and encouraging. Each illustration portrays a snapshot, laid out in comic book-style panels showing a young family carrying out a repertoire of everyday activities such as: looking at the washing machine whirl around, taking a bath, brushing hair, playing peepo, going for a stroll, collecting rocks, watching television, playing with teddies, Zzzzzzz. Are you struggling to still awake? That’s how I felt reading this book. When I say ‘reading’ I mean flicking through. There’s very little text which I’m guessing is the point. We are supposed to discuss the illustrations, however the activities they portray are so bland and outdated (baby and toddler strapped into the car via some harness contraption sans car seats; newborn sleeping alone in its cot) that you’d rather be discussing the weather with your mother in law. However in the book’s defence, there are some endearing illustrations of father-child interaction including different babywearing techniques.

Hello Baby!

Lizzy Rockwell

Hello Baby! plots the standard western experience of maternity: antenatal checks, ultrasound scans, decorating the nursery, the obligatory overnight stay with granny, the excited phone call from the hospital, yaddah, yaddah, yaddah. However what sets this book apart from its peers is the depth of both the images and text. Stylized but essentially realistic illustrations show calm, smiling characters. The book includes a chart showing the growing fetus from shrimp-like embrio with tiny arm and leg buds, to full-term bouncing babe. The velvety transparent amniotic sac can be seen alongside the placenta with pulsating umbilical cord. Once the baby arrives the illustrations capture both the skinny helplessness and surprising individuality of a newborn. In one scene the baby is shown being bathed by Dad who is carefully sponging around the delicate cord stump. The text is told from the perspective of the baby’s older sibling and is equally descriptive: “in mommy’s tummy the baby empties its lungs with water to make them strong”; the baby’s heartbeat “is loud and steady and faster than mine”. The breastfeeding scene is handled in a similarly eloquent fashion: “Right away, the baby is hungry. She sounds like a cat when she cries. Mommy nurses her in the rocker. Mommy’s breasts make milk that is the perfect food for a baby.” The mother is illustrated smiling dreamingly at her suckling newborn. She looks radiant. No eye bags, split ends or spit-up stains here.

Jump to Part Four