Here’s something to rattle your cages: Another trio of anti-breastfeeding books disguised as ‘helpful parenting guides’..

Positive Pregnancy

Denise Tiran

At first, I was worried that “Positive Pregnancy” would actually be positive in some fashion. You know, helping women have the safest, healthiest, most fulfilling pregnancy and postpartum experience. Yet the only thing positive about this book, is that it has an end.

Positive Pregnancy would have feminists gnawing at their fists. Got pregnancy backache? Piles? Heartburn? Sciatica? Well, this author thinks you should stop feeling sorry for yourself and spare a thought for the poor menfolk:

“Some men can feel jealous of the baby growing inside you, or neglected if you do not feel well enough to satisfy their needs. It is extremely important to take steps to overcome this – try to find a compromise, talk about the situation and, if necessary, seek professional help. In most cases, if you are in a long term stable relationship, the problem will pass as your pregnancy progresses. However, if you are not aware of any problems, this can be a warning sign for you to obtain appropriate help. Statistics show that a first pregnancy is the time most likely for a man to have an adulterous affair” (p32).

Ladies, it all hinges on you if your husband has an affair. Neglect him and he will stray – it’s a statistical likelihood, innit.

Goodness to Betsy! It’s like we’ve been sucked into Stepford and the women’s movement never happened. If you actually make it into labor with your marriage intact, the book’s retrograde attitude continues:

“While you are at home in early labour, he can join you in whatever distraction activities you choose, or he may prefer to wash the car or mow the lawn until you need him” (p110).

Car washing, lawn mowing. How about shooting a few pheasants? Slaying a bison? This book is as big on gender equality as it is on breastfeeding:

“If you and your partner have decided that breastfeeding does not appeal to you, or if you are returning to work soon after the birth, it can be more convenient and easier to establish formula feeding than breastfeeding. If you have any medical conditions which could be made worse by the exertion of breastfeeding, such as a heart problem, you may be advised to formula feed” (p193).

It’s the same old crumbling white turd: breastfeeding is dispensed with in favour of parental convenience. The risks of not breastfeeding go unmentioned. It appears that facilitating informed choice is not the aim of this book. Rather, mythical hurdles to breastfeeding – employment and medical conditions – are erected. Another common myth is quick to join the party:

“Unlike pregnancy, breastfeeding is the time when you really should be eating for two! Eat plenty of protein foods, vitamins and minerals, fruit and vegetables, to prevent illness and infections, and drink at least two to three litres of fluid daily” [emphasis hers] (p195).

There is absolutely NO – zero – nil – nadda – evidence that a nursing mother needs to eat or drink more than she usually would. As long as she eats when hungry and drinks when thirsty, she’s good to go.

First this book tells breastfeeding mothers to ‘eat for two’, then it warns of the following:

“Regular exercise will help you tone up and lose weight but you may not return to your ‘normal’ weight for some time, especially if you are breastfeeding” (p200).

GO FOURTH AND FIGURE. If you’re eating for two when you don’t need to, of course you aren’t going to be shedding the pounds!

Next comes the obligatory lists of the pros and cons of breast and bottle. For the latter, convenience and “being less embarrassed in public” are listed (p13). I shit you not, the book even lists two pros of bottle-feeding for the baby. Yup, this book has boldly gone there. It’s attempted to frame bottle feeding as better for baby. Wanna know what they are? Barrels were well and truly scraped to come up with these:

1. “May establish routine quicker than with breastfeeding”.

2. “Less risk of vitamin K deficiency than with breastfeeding (theoretical)” (p195).

‘Theoretical’…what the..?! If it’s theoretical, then why include it? Oh yes, because you’re scraping barrels looking for positive aspects of bottle feeding for babies. Fact – for the normal baby, there aren’t any.

NEXT!

First-time Mum

Hollie Smith

Next up, we have ‘First Time Mum’, which seems to have fallen from a formula feeder convention and can’t get up. This book should be appealing simply because it isn’t ‘Positive Pregnancy’,, but alas, no such luck. Whilst ‘Positive Pregnancy’ was at least written by someone with qualifications (a midwife), this specimen of trash was written by a lady called Hollie Smith, a pervasive breastfeeding-basher with zero qualifications in the arena. Despite this training deficit, Hollie has a handful of books under her belt, most of which relegate breastfeeding to an act to be done for no longer than six months (see here), whilst at the same time elevating bottle-feeding to be just as good ‘if done with love’ (see here).

So excuse me if I’m not brimming with optimism when I open Hollie’s latest offering ‘First Time Mum’, particularly as the first mention of breastfeeding is:

“I don’t mean to be negative about breastfeeding…” (p27).

Total buzzkill.

She continues:

“Twice, I gritted my teeth through the pain of cracked nipples and went on to breastfeed for four months (at which point, admittedly, my commitment foundered – but that’s another story)” (p27).

We’re not talking about an unbiased approach here, and it shows:

So, with the optimism of a parent about to change the diaper of diarrhoea-suffering child, I turn to the Feeding chapter. This leaky turd of a chapter arouses a horrified expression as I am confronted with the large bold-fonted title: “IS HE GETTING ENOUGH MILK FROM ME?”

“You might be worrying about providing enough milk for your baby if you’re breastfeeding. After all, if he’s getting what he needs, how come he seems to constantly want more?” (p70).

How come indeed; He’s feeding a lot? Could it be that he’s regulating supply..

“It’s tedious and tiring having to be so committed when the supply-and-demand system is being cranked up”(p70).

Suck it up buttercup. Parenthood isn’t 24/7 Hallmark.

No wonder Hollie believes breastfeeding is too much hard work, she thinks that in order to get a correct latch you need to go through a two page, 10 step mirror-signal-manoeuvre routine (p28-29).

On the other hand, to give this book its fair-dos, skin to skin is mentioned, along with Fenugreek capsules to aid supply. Yet conversely, the mega supply-boosting practice of baby-mooning is shunned as being in poor taste:

“Oh God, the thought of getting into bed with my baby and staying there for days horrifies me. I would have gone stir crazy” (41).

The inconsistency continues.. Whilst rooming-in is out, pacifiers are most definitely in:

“If your baby isn’t settled, or if he likes to comfort suck and you’d prefer he used something other than a piece of you to do so, you may find that offering him a dummy provides a helpful solution” (p65).

But ‘what about nipple confusion??’ the lactivist in you recoils. Apparently, this threat doesn’t even register on the book’s radar:

“If you want to give your baby a dummy, do. The only main drawback is that at some point you’ll have to take it away” (p66).

Indeed, nipple confusion is completely overlooked. Case in point:

“Some mums find that nipple-shields can really save the day” (p78).

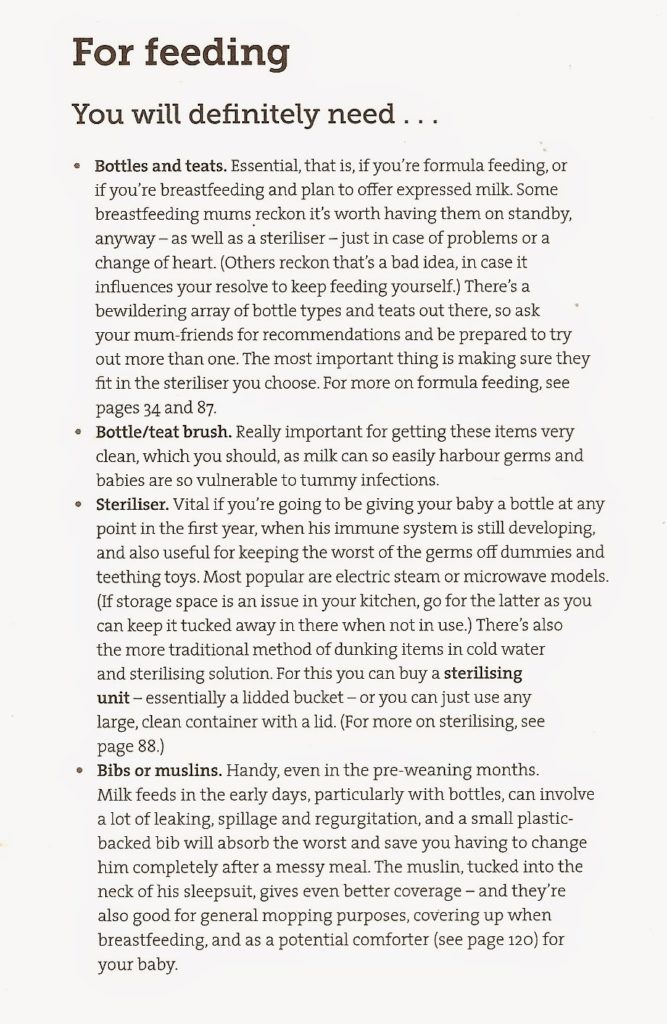

Oh, and while we’re talking about artificial nipples, according to Hollie, you’ll deffo need to purchase all this gear:

The truth is, if you have this shit ‘on standby’ as she recommends, and you’re giving yourself a one-way ticket to Quitsville. Listen here folks: keep all this paraphernalia out of your home if you seriously want to breastfeed. You wouldn’t stockpile cake if you wanted to lose weight. Keeping all potentially-sabotaging items outta hands-reach will give your willpower extra mojo.

On the topic of alien devices, the book’s small-ish section on pumping breastmilk recommends:

“It’s a really, really good idea – even if you’re exclusively breastfeeding and very happy with the arrangement – to offer your baby a bottle at quite an early stage if you know you’ll need him to take one in the future, perhaps when you return to work, or maybe when you’ve had enough of breastfeeding and decide to use formula instead” (p81).

A mother should use a bottle even when she plans on feeding exclusively from the source? All together now: ‘Ain’t Nobody Got Time For That!!’

The fact that the author only managed to breastfeed for 4 months becomes painfully apparent by her botched understanding of lactation; 2nd Case In Point:

“You may find a happy compromise in mixed feeding. Although be aware that once you swap a regular breastfeed with a bottle of formula, it won’t take long for your body’s supply and demand system to adapt accordingly. After a while, there’ll be no going back” (p86).

Whilst I appreciate the warning that formula introduction can lower breastmilk supply (correcto!), the assertion that ‘there’ll be no going back’ is utter tosh. Part of the awesomeness of boobs is that they are dynamic: less suckling – less milk, more suckling – more milk! Those girls swing both ways.

If adoptive women can lactate, biological moms can sure as hell recover their full supply after taking a few bottles of formula. Make no mistake, this is a vitally important fact – one that could help a majority of mothers salvage their breastfeeding relationships – yet this fact is commonly neglected or even denied in literature such as this, why?? Because relactation involves arseing about. It involves effort. It interferes with parental convenience. So, let’s pretend it doesn’t exist to make ourselves feel better.

Whilst we’re discussing convenience, no feeding chapter would be complete without a dip into the wallpaper-paste world of formula. Sadly, as to be expected, the risks of formula are omitted from the book – even the risks of incorrect hygiene:

“It’s easy to get in a bit of a pickle over sterilising rules and regulations, and of course, no-one wants a baby with a poorly tummy. If you’re worried that you’re not being scrupulous enough, you may be reassured to hear that some parents don’t sterilise at all, considering a wash in very hot soapy water or a run through the dishwasher to be sufficient” (p89)

Next, and true to form, this book adopts the same-old oxymoron, all too familiar in parenting books, whereby the author broaches the topic of ‘guilt’ and then asserts that formula feeding mothers shouldn’t feel guilty (go figure!)..

“Please don’t feel guilty about it if you’ve decided to formula feed your baby, or if you end up formula feeding because breastfeeding didn’t work out for you. Sadly, it’s a common reaction. But formula is a perfectly good alternative to breastmilk” (p34).

And just in case you’re hard of hearing, have memory issues or dead, the message is regurgitated later in the book:

“Please don’t feel bad about it (or let anyone else make you feel bad) if a breastfeeding problem turns out to be insurmountable and you end up reaching for the formula instead. It’s a brave woman who battles through potentially toe-curling issues like mastitis or thrush. And if you’re really struggling, remind yourself that what’s best for your baby, may not be the best thing for you. What your baby needs most of all is a happy, pain-free, and non-stressed out mum” (p78).

Translation: ‘Don’t feel guilty or bad if you formula feed. Happy mum – happy baby! Yadda yadda’.

So basically, being non-judgemental is about being vaguely judgemental to people who have a view you don’t like (those who ‘make you feel bad’), then patting yourself on the back for not being as fully judgemental as you could be. Hurrah!

Yet, of course, by linking formula feeding with guilt and bad feelings, the author is solidifying just that – guilt by association. She is implying that formula feeding moms should feel guilt. If guilt was truly irrelevant to formula feeding, it would not keep cropping up in the same sentences.

And while we’re looking at oxymoronish comments…

“It’s generally agreed that you can’t overfeed a breastfed baby, however often they seem to want to[sic] much”(p31).

Breastfed babies seem to want too much? Where the shit did they learn that? Dang that survival instinct!

Alas, the babies-as-hassle rhetoric is recycled:

“Babies often enjoy chomping on a boob for the comfort factor, long after they’ve actually taken their fill. That combined with the frequency of early feeds means that initially, breastfeeding mums can find themselves amazed (and often, very fed up) by the sheer proportion of their life spent releasing their breasts from their bra. They feel little more than a human milking machine” (p32).

Dude, breastfeeding is but 0.5% of a woman’s life, hardly something to get melodramatic over. Is donating 0.5% of your time over your whole life span really something to get your thong trapped over? When you consider the lifelong health implications for both your child and yourself, it’s a no-brainer.

Next, we’re treated to some specific advice: As you’re a milking machine, remember to stay well-fed, but not with cabbage, cauliflower, or any other farty stuff:

“Colic-causers: Some foods are said to be likely causes for colicky symptoms – strongly flavoured vegetables like cabbage and cauliflower, onions, caffeine, what, citrus fruits, dairy products, and anything very spicy are the usual suspects” (p73).

…so what exactly does that leave on the menu? Oh yeah.. Dust. Wonderful. Bon appetite nursing momma!

So far we’ve seen this book regurgitate the ‘mom’s diet causes colic’ rhetoric, the ‘guilt’ rhetoric and the ‘milking machine’ rhetoric. Resurrecting clapped out rhetorical devices is scaremongering propaganda at worst, lazy writing at best. Indeed, rhetoric becomes the core of the ugliness in this book (which is, really, wall-to-wall ugliness). There’s the:

- ‘Boobs-are-like-bottles’ rhetoric:

“Make sure each breast is completely drained” (p31).

(Note: you can never ‘completely drain’ a breast because mammary glands are constantly synthesizing. The mom who believes that breasts can be ‘empty’ is the mom vulnerable to ‘empty boob syndrome’ – a treacherous state of mind).

- The ‘Breastfeeding-in-public-eeeeewwww’ rhetoric:

“One drawback of breastfeeding is that you’ll almost certainly have to get your whammers out in front of people you wouldn’t normally: your father-in-law, for instance, and random members of the public” (p76).

- The ‘Lactating-breasts-eeeeewwww’ rhetoric:

“Sometimes it’s blokes who go off sex after birth. It’s possible he’s a bit turned off by your wobbly belly or leaky breasts: harsh, but potentially true” (p222).

- The ‘Nursing-moms-need-supplements’ rhetoric:

“Continue taking an ante-natal supplement, if you took one in pregnancy, or buy one specifically for breastfeeding mums, and ask your pharmacist about suitable daily multivitamin drops for your baby” (p75).

The only benefit to come from following this advice is to the supplement manufacturers – who rake in £385 million annually in the UK alone. There’s even evidence that supplements could do more harm than good. So, save your cash people, and simply eat well.

Another well-trotted quagmire commonly seen in parenting books is the push towards early solids introduction, and this book is, alas, no exception:

“The most recent research available suggests that weaning from four months is no more likely to be harmful than if you wait until six months. One 2011 study even flagged up the possibility that some exclusively breastfed babies really do need to get cracking on iron-rich solids a bit before six months, if they’re not to be at risk of problems like iron-deficiency anaemia. (This is unlikely to be an issue for babies who are on formula as it has more iron in it)” (p95).

Research this. Research that. Yes, it’s all well and good using the R word, but where is this research?? The book does not mention it by name, institution or otherwise. There’s no trace of which research is being referred to. It could have been carried out by Dr Who Polytechnic rather than the actual WHO. In fact, that would explain why WHO and the health department of each major government have overlooked this ‘recent research’, standing firm with their 6 month guideline.

As for the iron issue, the fact of the matter is that there is enough iron in breast milk to last an infant until at least 6 months. Just the right amount. Perfect. In fact, recent research (I’m talking 2013 here people) suggests that the iron in formula may actually be making babies ill. This is because many of the bacteria involved in infantile illnesses require iron for growth and replication (for more info, see my article here).

Next, we switch chapters from Feeding to Sleep. I’m suspecting that placing these two chapters side-by-side in the book wasn’t a mistake, as any dedicated breastfeeding-saboteur knows, every parent’s achilles heel is their sleep deprivation. The usual tripwire in such circumstances is to suggest tanking up baby with solids:

“You might consider – if you’ve been breastfeeding until now – giving formula as his last feed, instead, or maybe if he’s past the four-month point you’ll be tempted to whip up some baby rice and offer that at teatime in the hope of tanking him up” (p125).

Many self-fashioned ‘baby experts’ seem to think that babies should function like adults, suggesting that we tank them up during the day. Such an assumption may be true for us adults, with our large stomachs, but for a small baby with a tiny tummy, it just isn’t realistic or fair.

“Whether it’s a feed, or just your attention that he demands every time to get back to the land of Nod, he doesn’t actually need [her emphasis] it. And if you want to, you can teach him as much, by ceasing to offer what he’s looking for until he gets to the point where he realises he might just as well roll over and go back to sleep again instead” (p126).

Dude, we’re not talking about a husband with a boner here. We’re talking about a baby’s hunger. This is a sad misunderstanding of babies’ needs. The makeup of human breastmilk, with its relatively low fat content compared to other mammals and the speed at which it is digested, means that babies are not designed to spend lengthy periods without suckling. Human babies are meant to be close to our bodies. To use an unfortunately popular term, they are meant to be ‘clingy’, it is in our genetic makeup. Human babies are designed to require constant attention and contact with other human beings because they are unable to look after themselves. Unlike other mammals, they cannot keep themselves warm, move about, or feed themselves until relatively late in life. In other words..

“Bear in mind one really good reason not to invite your baby into your bed: you won’t easily get him out again”(p113).

Ho ho. It’s that old Chrimbo cracker joke again: the co-sleeping teen!

“..So if you do set up a heavy bed-sharing habit, be prepared to initiate a concerted turfing-out campaign, perhaps with the aid of a sleep training technique” (p113).

Oh nadds, I was wondering when sleep training would slink its way into the narrative. Still, what can we expect from a controlled crying fan (p128) and Gina Groupie?

“Gina Ford has a great many fans among mums who swear she helped them to have a contented baby, so it you think it could be the way forward for you, pick up a copy of her book, or check out her website, and give it a go”(p33).

I’ll pass. Shame this mother didn’t:

Relax, It’s Only A Baby!

Denise Robertson

Okay, Denise Roberton, you win. Somehow you’ve written something more vile, more petulant, and possibly dumber than anything even Gina Ford has ever written. Congratulations.

The title of this book says it all: “Relax, it’s ONLY a baby!”Translation: ‘Gawd, don’t sweat it. It’s not like it’s something important’..

I think this book may be a sign of the coming Rapture, or maybe just confirmation that formula company propaganda stretches further than the psyches of unsuspecting moms. In her first chapter, the author, Denise Robertson (a TV granny in her 80s, sans any qualifications), straps medical science to a rocket and fires it into south Lebanon:

“Don’t worry that inability to breastfeed will hinder bonding. It’s the closeness and the holding of the infant during the feeding process that strengthens the link between mother and baby –nd [sic] father and baby, too for the father who bottle-feeds his baby is also forging valuable links. It’s important to share the early days with your partner or willing grandparents” (p24).

Nevermind that breastfeeding actually restructures a mother’s brain; Nevermind that artificial feeding pulls the plug on the evolutionary waltz between moms’ and babies’ bodies; Never-fookin-mind that handing baby to every Tom, Dick and Harry can cultivate attachment issues, this book just wants Granny to have her some hands-on baba action. Obviously, as a granny herself, that’s the author’s prerogative. In the past, such horrible women with their blue-washed hair would have faded into obscurity, cursed to recycle the same tired, childish arguments at their local country club or knitting classes. These days, they get their own slots on morning TV shows. This country is going down the shitter, I tell you.

As we exit chapter 1, it’s worth noting that this book has, thus far, featured ten bottle feeding illustrations and zero breastfeeding illustrations, a suspiciously coddy whiff that gets even more fishy as the book progresses.

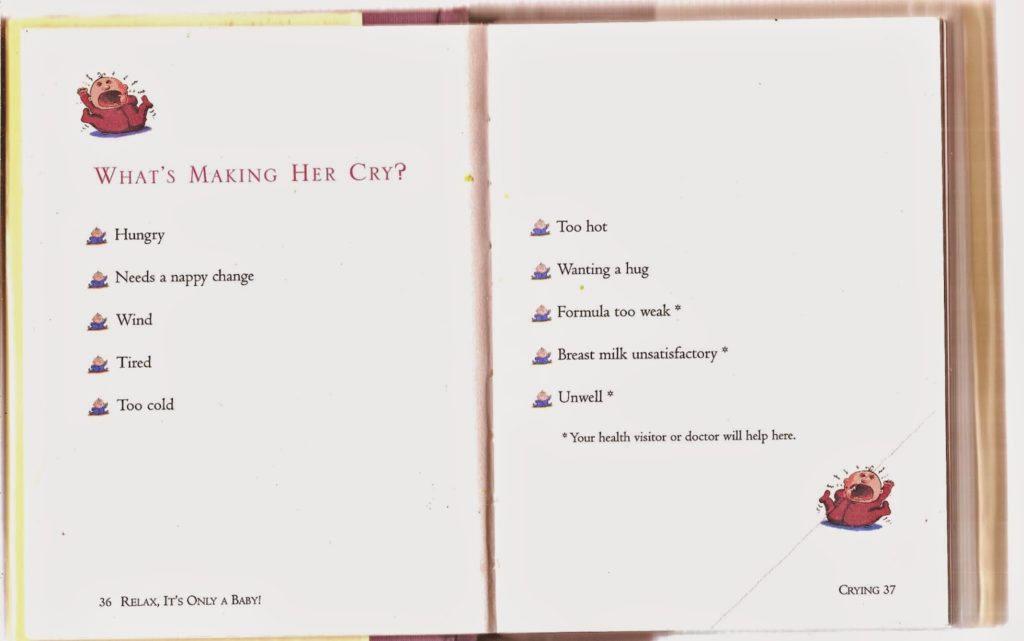

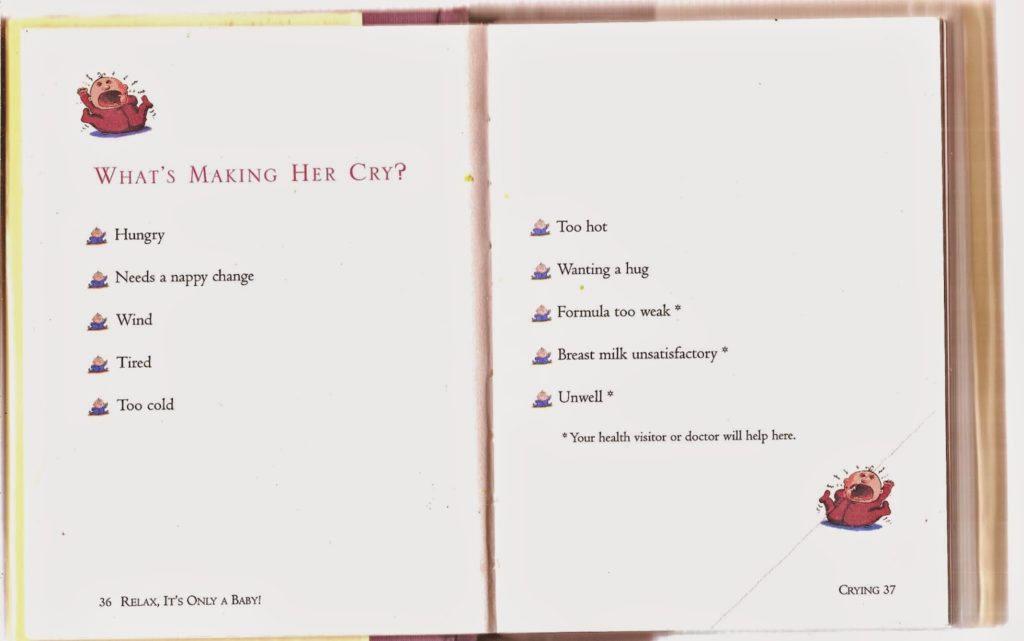

We turn to Chapter 2 and see that it is entitled, simply: “Crying” and is a measly four pages long, two of which I have scanned for your viewing pleasure:

Yup, that’s right, the book alerts mothers to the apparent fact that their baby may be crying because their breastmilk is – and I quote – “unsatisfactory”, with no explanation for what the heck that means or from what glitch in the matrix the author sprung from. Heck, the text is even accompanied by a little asterisk prompting moms to seek medical help for their malfunctioning mammaries.

..which brings us, not-coincidently, onto the next chapter: “Feeding”. You hear that creaking sound? Sorry. That’s just my teeth grinding in anticipation.

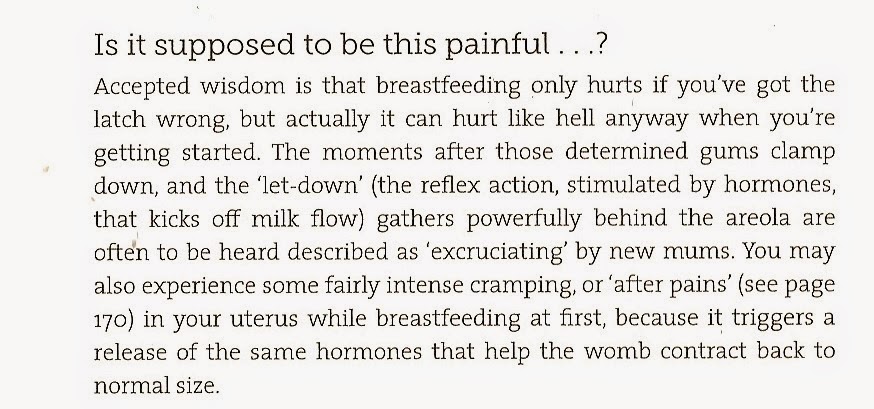

In this chapter we’re given the predictable spiel: breast is best but it’s no biggy if you can’t or don’t want to; you’d have probably gotten sore nips anyway;

bottle feeding has loads of ‘benefits’; etcetera, etcetera. If, after reading this standard propaganda, you still insist on breastfeeding you’re instructed to block-feed (p43) – a sure recipe for drying up the Milk Bar.

The feeding chapter is only 6 pages long, and quite frankly, that’s a blessing. Especially when you consider that (subliminal messaging intended or not) the bottle image count is now up to 20 now and just one (ONE!) breastfeeding pic (the little sucker measuring precisely 1.3cm – they couldn’t even give us an inch!) We’re only up to page forty five FFS! That’s one boob illustration for every 20 bottles. Sad times, people. Sad times.

Here’s just a smattering of what I’m talking about:

To save you some reading (and me some writing) let’s just say the book is sans any value. It’s utter trash. Oxfam wouldn’t want it for their stores; heck – even my guineas would disown me if I tried to line their cage with it. The thing advocates controlled crying (p58),

routines for 4 week olds (p69), and weaning if your baby so much as glances at an edible food source (p92). The author recommends introducing solids at 4 months (p93) and prescribes mush over BLW (p94).

On the topic of extended breastfeeding, the author’s opinion is: How very dare you! (This is actually a pic of the author, no bull, she be judging):

Don’t you know “breastfeeding gets more difficult to stop as your son gets older and can assert his will” (p94).

Well that’s us told.

Spread the word – pin it!

Wanna see the entire fleet of anti-breastfeeding books I’ve exposed so far? Really, you wanna put yourself through that shit? Okay, you’re in luck.. click away:

| Part One |

Part Two |

Part Three |

Part Four |

Part Five |

Sleep Training Edition |