It’s a sad day when you reach Part Three in a series exposing the popular preoccupation with berating breastfeeding. Yet instinct and experience tell me this won’t stop at a trilogy.

If the previous instalments (Part One and Part Two) made you reach the end of your tether, you’ll need to find a lot more tether for this one. Much of the ‘advice’ in the following books smells like the diaper of a formula fed baby. It is parent-centric and resentful of babies. It teaches parents how to ‘train’ their babies to become acceptable, or at least, less of an inconvenience. Hold your breath, we’re going in.

Baby and Child: Your Questions Answered.

Carol Cooper

We’ll start the ball rolling with a tame beast; but a beast nonetheless. This book’s greatest sin lies in its misinformation. Rather than having obvious in-your-face contempt for breastfeeding, the book undermines more subtly by force-feeding the reader with incorrect advice. Much of this advice has the potential to completely sabotage a mother’s breastfeeding efforts. The book commences with the chapter: “Feeding Your New baby”. It begins:

“In general, breastfeeding is better, but, as it’s your baby, you must decide which you want to do. Before you commit yourself, there are many points to consider” (page 32).

Tentative start.

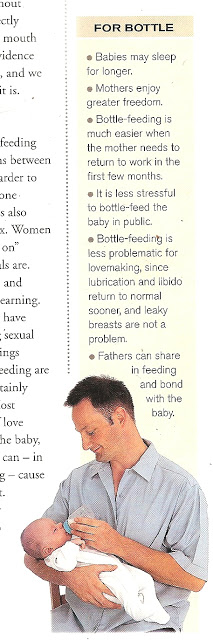

Then we are presented with a basic table detailing the advantages of breast and formula feeding. The usual textbook points are made for breastfeeding – antibodies, cheapness, nicer smelling poops, all the usual jazz. However it’s the list of advantages to formula feeding that has me cropping my eyebrow like James Bond. Check these out! Under “Your’s Baby’s Health”, the list of advantages to formula are listed as:

“Your baby’s supply of milk is not affected by your physical health, nutrition or anxieties”.

(Yet neither is breast milk, for the most part).

“She is less likely to be underfed”.

(Codswallop. A formula feeding mother can easily under-feed her baby when she does not measure the powder properly – for instance, she may add too much water or too little powder).

“Whilst breast milk is superior in many ways, formula milk is higher in iron and vitamin K”.

(This is based on the assumption that the more of a vitamin a product contains, the more nutritious it must be; however in fact, breast milk has a perfect blend of vitamins at an ideal concentration for human babies).

“If you are vegetarian, your baby might be less likely to develop a vitamin B12 deficiency”.

(A vegetarian or vegan mother does not need to take any special dietary precautions; she simply needs to follow the same diet as any other new mother).

Okay, that’s the apparent advantages of formula to baby’s health. Now the advantages for mom’s health:

“It does not expose your breasts in public places”

(What does this have to do with ‘health?’)

“Milk will not leak from your breasts and stain your clothes”

(Again, what does this have to do with ‘health’??)

“Your nipples will not become sore or cracked”

(Neither do those of most breastfeeding mothers!)

That’s it for mom. Then the book presents a FAQ-style section which basically reads as a catalogue of bitch slaps to breastfeeding. Notable examples include:

“Q: If I have large breasts, could my baby suffocate?

A: It’s possible for large breasts to block your baby’s nostrils, making it difficult for her to feed and breathe at the same time. You can press the breast down just above the areola to give her nostrils more space” (page 33)

This is great advice …if you want blocked ducts and mastitis.

“Q: If I breastfeed my baby, will my breasts sag later?

A: Breastfeeding may have some effect” (page 33).

(I call a big steaming pile of formula-fed-baby’s crap on this one!)

“Q: Can I exercise when breastfeeding?

A: Very vigorous exercise is not recommended; It is said to increase the lactic acid content of the breast milk” (page 39).

(A mother would need to exercise to maximum 100% intensity for her breastmilk to contain a measurable quantity of lactic acid. Besides, there are no known harmful effects to a baby exposed to lactic acid. Next!)

“Q: Is it a good idea to give a bottle of formula as well as breast milk?

A: It can be a good idea to offer a bottle in the early evening when breast milk supply is likely to be low” (page 41).

(It’s true that breast milk supply tends to be lower in the evening – for this very reason your breasts need all the stimulation they can get. Giving your baby a bottle will deter him from suckling at the breast, thus reducing your supply further. It’s exactly like giving your baby a McFlurry then wondering why they won’t eat the fruit bag. In fact, from a nutritional viewpoint it’s exactly like that).

“Q: I feel guilty about bottlefeeding.

A: Formula milk is almost as good nutritionally as breast milk” (page 45).

(Yes and Jimmy Savile is almost as child-friendly as Mr Tumble. What? Too soon?)

“Q: Should I start using a pacifier to comfort my baby?

A: Pacifiers are more useful before the age of six weeks”.

(You read that correctly – encouraging pacifier use without mentioning the risks to breastfeeding – tut tut, slapped legs all round). Can we move onto something a little more hardcore now? Gurgle.com step up!

Feeding: Solved, from Breastfeeding to First Foods.

Gurgle.com

Woah, this book mentions breastfeeding on the cover. It must be an authority on the subject! Before we look at the contents, let me introduce the author. Gurgle.com is a British pregnancy and parenting website owned by high-street parenting store Mothercare (Mothercare is not Code-compliant by the way). Gurgle.com hosts regular online webchats with parenting ‘experts’ and celebrities. Recent webchats have included: Tess Daly (who advocates that breastfeeding mothers use bottles at night), midwife Vicki Scott (who works for bottle manufacturer Philips Avent), Myleene Klass (who coined the phrase ‘Breastapo’), and professional beacon of breastfeeding knowledge, Dr Miriam Stoppard (who has said that babies with teeth should stop breastfeeding). This list reads like the lineup at a comedy sketch; however this is childcare advice we’re talking about; and it’s targeted at vulnerable new mothers.

The book begins with a chapter titled “Breastfeeding: the lowdown” (or should that be ‘letdown’? ho ho). The contents of this chapter are a vague as the title. First we are given the standard, ‘there-there’, pat on the back to formula feeders:

“Don’t torment yourself with guilt about it, as your baby will still receive all the nutritional benefit he needs from formula milk” (page 10).

Oh really? So why are formula fed babies at an increased risk of cot death, diabetes, ear infections, allergy, etc? If they were on an even nutritional keel with breastfed babies, they wouldn’t have these disadvantages no? Also consider who the target audience for this book is – mothers to be. The message they get from this simple sentence is: if formula fed babies receive all the nutritional benefit they need, why bother breastfeeding? What a great start to the book.

Later we are told why babies are fussy:

“Your baby may become frustrated because he is not receiving the milk he needs to fill up his tummy” (page 20).

Babies have tiny tummies, about the size of their fist, so they need to feed frequently around the clock. The ‘frustration’ the book speaks of may actually be baby’s cue to feed again, as he has processed the milk in his tiny tummy. Yet the book frames it as ‘baby not receiving the milk he needs’. This exploits the common fear amongst new mothers, that their breastmilk is insufficient; a fear promulgated by a bottle feeding culture which prioritises measurement of intake. The fact however, is that most of babies’ frustration has nothing to do with hunger. Wanting to feed is notthe main reason babies cry (Spock 2004). Discomfort, boredom, and the massive shock to their sensory system that is NEW LIFE ITSELF – are more likely causes. Everything is new to babies: imagine landing on a planet where nothing, not even air or shapes or colours, is like anything you’ve experienced before. Imagine you’ve never felt anything on your skin or digested food – you’d cry too! Especially at the end of the day. Babies cry. This is a fact of life.

Speaking of facts, you won’t find many amongst the pages of this book. Nuggets of fiction dressed as fact include:

“When your breasts feel emptier, it’s time to change breasts” (page 23).

Given the bottle-centric origins of this book, this sentence is hardly surprising. However breasts are not bottles; they do not get ‘empty’. Even when a woman’s breasts ‘feel empty’ – they are not. It is the baby who should decide when to switch breasts, by latching off and being disinterested. Furthermore, at around 6 weeks a woman’s breasts will naturally start to feel emptier relative to the fullness hereto experienced. This is normal. Her body has regulated to meet her baby’s demand. However if the woman in question were to read this book, she would get the impression that her breasts were ‘empty’ and she would panic. This ignorance is what leads many women to quit breastfeeding around the 6 week mark.

Another area of breastfeeding that is commonly shrouded in ignorance is the dilemma of which breast to feed from first. The book answers this conundrum:

“Start feeding your baby from the breast you last fed on; This means each breast will receive the right amount of stimulation to ensure good milk supply” (page 23).

This technique is called “block feeding” and is only recommended for women with over-supply. Block feeding slows milk production, and if adopted by women of average milk supply (that’ll be most women then), it can seriously reduce their production. So this book is actively sabotaging mothers, and it even cites “enhancing good milk supply” to justify its advice. Bitch please!

Another of the book’s strategies of sabotage is to frame breastfeeding as shameful, particularly when done in public. It recommends that:

“A shawl or big scarf can help protect your modesty if you are planning on feeding in public” (page 23).

The assumption is that nursing mothers must hide. No other approach is suggested. More assumptions are made on the topic of introducing bottles:

“Introducing your baby to a bottle, if you are breastfeeding, is actually a good idea” (page 32).

Again, the issue here is what is left unsaid. The book fails to mention the potentially detrimental risk of nipple confusion and reduced supply.

Speaking of reducing supply, if you want a free ticket to breastfeeding failure, why not force your baby to adopt a feeding routine:

“Babies love routines and they’re good for parents too” (page 72).

At this point you may be thinking that introducing a routine to a 6 month old breastfed baby would be fine, as by that point breastfeeding has been established, milk supply has regulated, solids are being introduced, and baby might even be sleeping through the night. Well you’d be right. A routine at 6 months isn’t necessarily going to spell curtains for your breastfeeding relationship, but this book advocates adopting a routine much sooner than that:

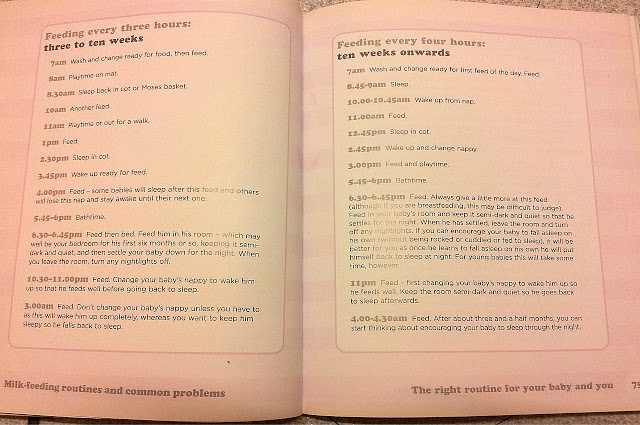

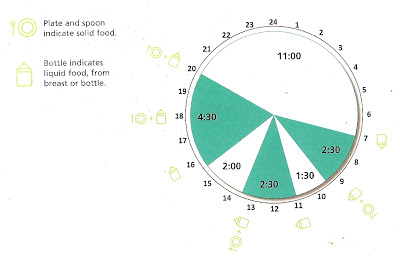

“Here is a routine suitable from three weeks” (page 72).

*Three weeks*! You heard me soldier. Your little squaddy has only been out of the womb for 3 weeks, but God Dammit he better fall inline. Take a gander at your instructions:

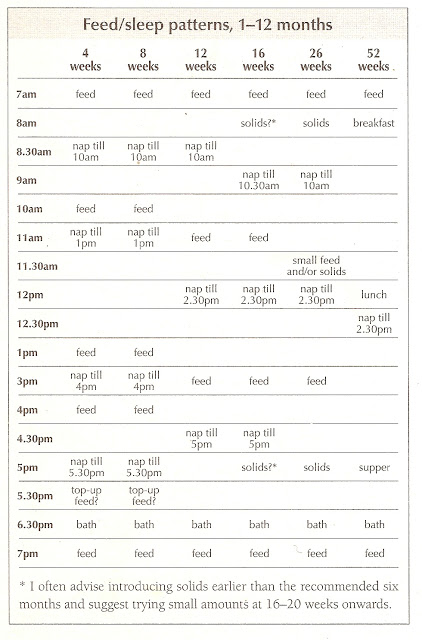

Gina Ford would be proud.

However needing to get your baby on a strict schedule from the get go is nothing more than a pavlovian myth, and doing so may be dangerous, because her body is not developmentally ready to wait several hours between feeds or sleep periods. It helps to clarify the issue if you think about the learning process that your baby has to go through. In the womb, she was fed more or less constantly; once born she has to learn to accept that there will be times when she feels full, and times when she is empty. This is a big, scary change for her.

If you’ve followed the book’s advice so far, your life probably looks something like this: You see your baby’s every whimper as a signal of your dwindling milk supply; you feel your breasts and they feel ’empty’; you block feed and wonder why your baby’s diaper output is going down; you hide under an burqa in public; you introduce a bottle because for some arbitrary reason it’s “a good idea”; and finally you shoehorn your baby into a scheduled routine. After all this, you’re left wondering what’s the point, as “your baby will still receive all the nutritional benefit he needs from formula milk”. You’re hanging on by a thread; so you turn the page and begin the chapter on bottle feeding, where you find the final shunt:

“Formula milk has been rigorously designed to ensure that it supplies the best possible combination of vitamins and other nutrients” (page 50).

Yup. You read it correctly. “The best possible combination of vitamins and other nutrients”. The *best*. I admit, in all my years of academic research, this is a new one to me. As breastfeeding is the normal way to feed your baby, this book is actually elevating formula above breastfeeding, accompanied by a lovely photo of a formula feeding mother kissing her baby on the forehead whilst she administers the breastmilk substitute. The book even has the cheek to advise mothers to:

“Ask your health visitor or GP for advice as they probably have a favourite brand that they can recommend” (page 54).

Oh I bet they do; considering how relentlessly formula companies market to health professionals; and this marketing is completely unregulated, even less so than other print media (see here). So directing formula feeding mothers to ask their health professional for their favourite brand is likely to subject them to yet more marketing, rather than an accurate medical analysis of the different formulas available.

The next chapter in the book looks at “Common Feeding Problems”. I was pleasantly surprised to see tongue tie being given it’s very own section with three entire pages devoted to the condition. However my pleasant-surprise turned into WTF-surprise, and then to fuck-this-surprise, when I read the closing paragraph:

“Babies rarely need treatment for tongue tie as they tend to adapt” (page 99).

This basically feeds into the misconception held my many misinformed health professionals, that releasing a tongue-tie is medically unnecessary, thus denying mothers and babies of the treatment that could save their breastfeeding relationship.

Another medical inaccuracy that sabotages mothers is the belief that lactose intolerance is incompatible with breastfeeding. On page 163 the book orders that:

“Babies with lactose intolerance will need to be taken off breast or formula milk straight away and given a special low-lactose formula that is only available on prescription from a doctor”.

What the book fails to mention is that there are in fact, two different kinds of lactose intolerance: primary lactose intolerance and secondary lactose intolerance. The first kind is extremely rare and requires cessation of breast or formula feeding. The second kind is the most common and does not require that a mother stop breastfeeding (she will however have to stop using standard formula if she is bottle feeding). Why does the book focus on the rarest kind which requires mothers to quit breastfeeding yet neglects to mention the kind which enables the mother to continue breastfeeding? After all, the most likely scenario is that if a baby is lactose intolerant, it has the most common form of the condition which is fully compatible with continued breastfeeding. The plot thickens…

After rolling my eyes out of their sockets I turn to the next chapter, which is titled, “Starting Solids”. In this chapter we see Miriam Stoppard’s influence wafting around each page like a fart trapped in a conference room. Basically the chapter coaches mothers on how to mis-read their baby’s signals. Growth spurts are not acknowledged; instead they are used as ‘evidence’ that breast milk alone is not satisfying the baby and so they need solid food:

“There are a few simple indicators that your baby might be ready for solids. For example, if she doesn’t appear satisfied by her milk feeds, perhaps waking in the night when she didn’t used to, this can indicate that she is ready to move on” (page 104).

Suggesting that milk alone does not satisfy babies prays on a weak point in the mechanics of breastfeeding – the fact that you cannot gauge how much your baby is consuming. This isn’t normally a problem in those parts of the world where there are no scales and no doctors; the mother simply assumes the baby is receiving plenty if the child acts contented and looks well and this works well in the vast majority of cases. However we live in a society fixated on measurement and quantifiable results. Combine this with society’s fetish for chubby babies and it becomes clear why premature introduction of solids is so common.

According to the book, another sign that your baby wants their immature guts violated is:

“Your baby will probably give you signs that she is ready for solids; for example, a loss of interest in or complete refusal to breastfeed” (page 107).

In reality, refusing the breast for a prolonged period (known as a ‘nursing strike’) is more commonly caused by teething discomfort, and introducing solids is likely to aggravate the baby’s condition further.

Yet it seems this book will say anything to reduce babies’ access to the breast. Take for example, the section titled, “Why does my baby wake in the night?” It maintains that:

“Many babies find it hard to settle themselves back to sleep and get into the habit of nodding off while having that last breastfeed at night” (page 144).

There is no mention of formula-fed babies falling asleep while having their last feed of the night. In fact, falling asleep after a formula feed has the added negative of bottle rot, which is a syndrome characterized by severe decay of the baby’s teeth (if you’ve got a tough stomach, Google ‘baby bottle teeth’). But of course, this is not mentioned in the book, because we’re only bashing breastfeeding here, silly!

A final fist in the face of breastfeeding, occurs in the last chapter, “Helping your child avoid weight problems”. The text asserts that:

“Avoid grazing if you are breastfeeding. Grazing is when a baby feeds at frequent intervals rather than at set times. A baby who grazes could become a toddler or child who comfort eats” (page 201).

Has this book ever heard of growth spurts?? Cluster feeding, or ‘grazing’ as the book calls it, is an essential survival mechanism. It is designed to stimulate the mother’s breasts to produce more milk. ‘Grazing’ usually occurs at night, which makes it particularly irritating to parent-centric mommies and daddies. Fortunately for them, a wide range of ‘Sleep Training’ books are available to put a stop to the all-night milk buffet. Oh, here comes one of them now!

Sweet Dreams

Arna Skula 2012

The title, ‘Sweet Dreams’ suggests tenderness and contentment. However, there’s certainly nothing sweet about this book, particularly its attitude towards babies (aka irritating, inconvenient little tyrants!)

The back cover lists all the highly coveted accomplishments the book promises:

“Correct your baby’s sleep timings and rhythms”

(i.e. babies’ are to be ‘corrected’),

“Teach your baby to fall asleep alone, day and night”

(i.e. teach them that no one gives a fuck about their needs),

“Use the specially designed charts to see what’s normal at any age”

(i.e. babies are robots who can all be programmed to adhere to an arbitrary norm).

But where does breastfeeding come into this? Although the book focuses on babies’ sleep (or rather, how parents can force their babies to sleep more, sleep quietly, and sleep when it’s convenient), sleep is not an isolated part of a baby’s life – instead it is intertwined with factors like development, personality, and nutrition. The book sees nutrition as yet another factor you can manipulate. However manipulating nature, as any failed breastfeeder will tell you (whether you want to know about it about it or not), almost always ends in tears.

So how does the book go about manipulating breastfeeding? First things first, it maintains that under no circumstance should you co-sleep:

“It’s important to get your baby used to the idea of sleeping in a place that belongs to him, in his own little ‘nest’”(page 17).

Still want to co-sleep? Naughty you.

“You’ll do anything you can to sleep a little longer, even just for a few minutes. You may, therefore, choose to stay in bed to feed (particularly if you are breastfeeding), which can result in your baby spending much of the early morning on the breast and it will be very unclear to him when the day begins” (page 82).

So, firstly the book wants to deprive your baby of the family bed; Next up, it wants to deprive him of night feeds:

“In general, when it comes to improving or changing a child’s sleep, it helps if someone other than the primary carer (usually the mother) takes care of the child for the first few nights” (page 22).

But Daddy hasn’t got boobs. How will baby feed?

“A breastfed baby has no more need for night-time feeds than a bottlefed baby. The reason that breastfed babies wake up more often at night probably has nothing to do with nutrition, but rather with the routines and habits involved in breastfeeding. It is quite likely that it’s mothers’ own insecurity that is responsible for the higher rate of night-time feeding among breastfed babies” (page 38).

This is dangerous advice. Firstly, it is dangerous because all young babies need night feeds, regardless of feeding method; this is a survival mechanism consequential from having a tiny stomach. Secondly, it is dangerous because the hormones responsible for maintaining milk production are more susceptible to stimulation at night; lack of nocturnal stimulation breaks the milk supply chain. Thirdly, it makes me want to bitchslap the author, which is very dangerous (for her) indeed.

Later on in the book, the author makes a suggestion. Check out this tip:

“Try to skip the midnight feed every now and then and see how long your baby can stay asleep without it” (page 90).

Manipulating a baby’s nutritional needs is not an experiment. It’s not like having a snag in your stockings and waiting to see how long you can get away with it. Babies are vulnerable and wholly-dependant. When their needs are left unmet for a period of time, they freak out and are too young to comprehend that they are being ‘trained’. Furthermore, growth hormone levels are much higher during sleep. Thus, the saying, ‘he seemed to grow an inch overnight’. Growth hormones also stimulate hunger. Waking to feed frequently is the baby’s way of making sure he has enough fuel to do the growing.

Yet not content with merely skipping one feed, the book later suggests going cold turkey and giving up night feeds altogether (I can hear mastitis calling!)

“Babies are usually strong-willed and determined. If your baby is like this, stopping night feeds completely may be an easier undertaking than reducing them little by little” (page 104).

Yet if babies could voice an opinion, they would say, “Nonesense! I’m not ready to handle life on my own, not yet”. And they are right. Eventually babies do learn other ways of comforting themselves and dealing with discomfort. But for now, they are learning about trust and security while feeding at the breast.

Following on from the anti-cosleeping, anti-night-feeding instructions, the book then goes on to order distance between mother and baby:

“If your child sleeps in your room, you should sleep in the living room (or another room). Sleeping in the same room as your child means your presence can easily wake him (even if you are quiet, it is not noise but your presence that is disturbing). If your baby is still breastfeeding, try not to hold him the same way you do when breastfeeding as you put him to bed or when you take him in your arms at night. Hold him facing away from you, or against your shoulder” (page 23).

Later in the book, parents are reminded:

“Don’t make eye contact or talk to your baby. Be as reserved as possible” (page 61).

“Babies are born with the ability to fall asleep on their own, or ‘self-soothe’ as it is sometimes called” (page 73).

This is simply untrue and ignores basic biological fact. For safety’s sake, babies are born hard-wired to awaken, which means that if anything threatens their well-being (such as SIDS) they wake up more easily than adults do. Training babies to sleep too deeply, for too long, too young is not in the best interests of the baby’s development and well-being. Yet the book maintains:

“It’s realistic to expect that, at around two months of age, your baby’s night-time sleep will last about eight hours”(page 82).

Two months! Sadly, that is not a typo, this is an actual deadline, but try saying that to a young baby with an empty tummy!

At two months, most mothers understandably feel they do virtually nothing but feed the baby. Books such as this one, with their fantasy 8 hour stretches, undermine mothers’ confidence. In fact, anthropology shows that prolonged night feeding is actually the norm in most human societies outside Western cultures. Playing tricks to lesson night feeding in the early months only serves to lessen your milk supply, so that baby fails to thrive.

Picture the scene: new parents read this book; then suddenly one night, their newborn baby finds himself moved from his parents’ bed into a dark, silent room on his own (against SIDS guidelines of course). He cries from hunger (and probably fear). When a parent arrives, he cannot see them; his body is held away from them. They don’t talk to him. They won’t feed him. They won’t even look at him. He’s too scared to sleep and no one will reassure him. Does this sound like a recipe for ‘sweet’ dreams? (the title of this book). The fact is that very few newborn babies have the ability to self-soothe. There are no bad habits at this age; your baby legitimately needs your help to fall back to sleep. One of the best gifts you can give your child is to grow up feeling that bedtime is a happy, peaceful, stress-free time to look forward to every night.

The imagery of a parent reluctantly holding their baby at arms-length suggests two people at odds with each other. Indeed the book frames the topic of sleep as a battle of wills – Baby vs Parents; and the ultimate looser must be the baby, whom is shoehorned into the parents’ desired lifestyle. However being a parent isn’t about adapting your baby to suit yourself; rather, it’s about adapting yourself to suit your baby. This book has conveniently forgotten this fundamental facet of parenting, and instead wages war on babies. Take this example from page 91:

“A baby’s self-image starts to develop right from birth. Your baby perceives himself at first as part of you, his mother. Like most babies, your baby then learns to distinguish himself from you without you being aware of the process. Your baby slowly starts to perceive that he is one individual and you are another” (page 91).

So far, big wow. Nothing controversial there. But then comes this left hook:

“However it can take some time for babies who spend a lot of time with their mothers to make this distinction. If your baby goes for a long time before understanding it, he may start to act selfishly towards you, as if you are supposed to do exactly what he wants. To help your baby learn this lesson, the most important thing is to get others involved in his care” (page 91)

Then we have this gem:

“If your baby cries the whole time you are away, it won’t hurt. It’s important not to let behaviour like this faze you. It’s nothing serious and doesn’t merit any particular response” (page 93).

IN YOUR FACE Stay At Home Moms! (and dads). F-YOU attachment parenting! UP YOURS child development! – is basically what the book is saying. It’s arguing that babies are essentially little bastards that will take the piss given half the chance:

“Your baby has to realise that he isn’t in charge of everything and that the world doesn’t revolve around him”(page 126).

News Flash! Babies are innately selfish. They have to go through a prolonged period of being dependent on others to achieve the kind of emotional security that is the foundation of later independence. Babies are not ready to move on to the next stage until the needs of this stage are fulfilled. They don’t have the developmental abilities to be independent at this age. This is normal, healthy, self-protective behaviour. However this author gives normal behaviour the finger:

“It’s easier to teach a baby these things before three or four months of age. Around three or four months of age, you will start to notice your baby protesting about certain things more systematically than others. He will start to have an opinion about who puts him to bed and who does various other things for him” (page 93).

“With his burgeoning new skills, your baby now starts to grope towards an answer to the question of who is in charge in your household” (page 104).

Sadly, these views are typical of Cry It Out fans; but is baby’s crying really about defiance? Or do baby’s cries express real human needs? The CIO club insists that babies cry at night because they want their mother’s attention, not because they need it. In order for the CIO method to pass muster with caring parents it has to downgrade real needs into mere wants. However, in young babies, needs and wants are pretty much the same thing. And in older babies, wanting to be held could still be viewed as a need – an emotional need for comfort. More worryingly, medical problems can be missed because a baby is left to CIO. The bottom line is that, babies cry to communicate, not manipulate. Yet this book maintains that babies are very much manipulators, and for the large part, breastfeeding is to blame:

“She knows that only Mommy has milk and so she obviously wants her. Of course, she will just be pushing the boundaries here and needs to learn that although she might prefer one parent over the other to do a particular thing for her, that doesn’t mean that you will always be able to grant such wishes. You need to calmly stand your ground” (page 103).

The misguided resentfulness continues:

“Around four months of age, babies often start waking up more frequently and feeding more at night. At six or seven months of age, this tendency becomes even more noticeable. Those babies who wake up to feed start to explore how far they can push things or, as they might say, “How often will they allow me to feed?” or “Well, if I can feed once, could I maybe feed three times? Why not try?” (page 38).

Reading this you might begin to think of babies are manipulative little demons. How dare they seek human contact and sustenance. They’re taking the piss! Can’t we just shut them in a shoebox for the night?

However if you’ve got any compassion and an elementary knowledge of child development, you would know that the baby in question is experiencing a growth spurt (which typically occurs at 4 months then again around 6 months – the exact periods cited). Baby is not trying to manipulate you, instil control over you, or pwn you in any way. Babies of this age are governed by survival instinct. Furthermore, reducing night breastfeeds is actually counter-productive to sleep, as naturally occurring chemicals in breast milk that are linked to sleepiness, called nucleotides, reach their highest concentration at night.

Yet the book won’t quit. Two pages later, it’s still droning on:

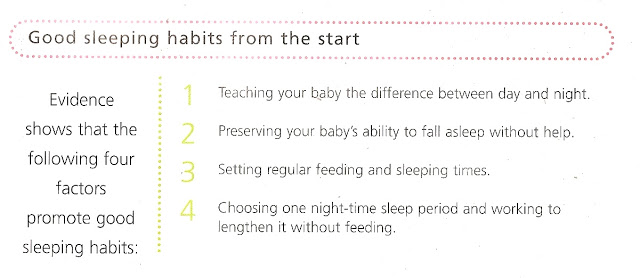

“Babies who want to feed frequently and in small amounts tend to want to sleep frequently and in small amounts. Bringing more order to a baby’s feeding schedule will often have a positive effect on her sleeping rhythms” (page 40).

Like a Breastfeeding Vs Formula Feeding internet thread, the book is still fruitlessly labouring on this point, many pages later:

“For newborns, feeding and sleeping are connected, which is why there is a link between regular feeding times and regular sleeping times. A baby who, for example, drinks quite often but never takes very much at a time is also likely to want to sleep frequently but never for very long. If your baby is like this, you may want to lengthen the naps she takes, and it’s easiest to do so by lengthening the time between feeds” (page 77).

So the book is advising that you lengthen the period between feeds, whether your baby is ready or not. It does so again here:

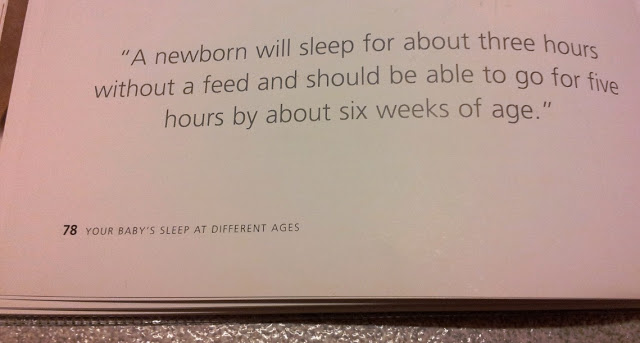

“You can expect your newborn to be able to go three or four hours between feeds. Your baby will stop night-time feeds earlier if you work slowly and deliberately, to lengthen one of her periods of sleep” (page 78).

A book shouldn’t tell you when your baby needs to be fed. We eat when we’re hungry, why should we make our babies wait until it’s ‘time’ to feed? Scheduling feedings too rigidly, too young is risky. One of the most common causes of ‘failure to thrive’ syndrome is failure to listen to and respond to baby’s feeding cues. Yet the book cites that sleep-training should occur from birth(!), and even babies who weigh as little as 6lbs are suitable candidates! Using a Q&A format, the book introduces us to a poor, knackered factional mother who, like every new mom, is suffering from a distinct lack of Zs:

“Q: My son is a month old. I’ve been told I should breastfeed him whenever he wants, and he wants to frequently. He is almost constantly on my breast in the evenings and all the way up to 2am when he finally falls asleep” (page 80).

All sounds perfectly normal to me. A mother’s supply slightly diminishes in the evening, whilst prolactin levels increase, making evenings the ideal time for frequent nursing (biologically speaking, if not socially). So what advice does the author give to this bewildered new mother?

“A: The first thing I think you should look at is your breastfeeding routine. You said that you have been told to ‘breastfeed whenever he wants’. In fact, you should breastfeed him whenever he needs but sometimes it can be a little hard to work out when a baby needs to feed. The risk is that your baby will start to get fed every time he cries, or almost every time – and he may be crying for many reasons other than hunger. He could also start using you as a pacifier.

It isn’t ideal to have a baby constantly on the breast in the evenings as you describe. Enforce some minimum time that you will hold him – say, an hour to begin with – between feeds. With some babies breastfeeding sessions run together, so that the baby starts spending a long time drinking. If this is the case with your baby, you will have to ration the time that he is allowed to drink.

You say he always falls asleep while breastfeeding. You need to train him to fall asleep on his own. Your baby dozes a lot in the evenings while breastfeeding, and though this is cozy now it is not ideal in the long run. Try to create at least some basic routine for breastfeeding: irregular feeding often leads to irregular sleeping! Let his father look after him in the evenings, even if your baby complains about this – the two of them will be able to work it out.

This advice may seem a little at odds with what you have been told, but hopefully it’s not too confusing” (pages 80-81).

I’m loving the last sentence. It’s almost as if the author knows she’s talking bollocks, so has to excuse herself.

Let me get one thing straight: breastfeeding is nature’s plan for comforting babies and helping them fall asleep. That’s why breast milk contains a sleep-inducing protein that helps lull a baby into dreamland.

Just in case your eyes haven’t yet popped out of their sockets in a manner resembling the dude from Beetlejuice, the book continues:

“If your baby has trouble holding out until her next feed, she may find it easier if someone other than her mother tends to her in between. This is especially true for breastfed babies” (page 78).

However, as I’m sure you’re aware (you read this blog after all) when breastfeeding, it is important that the breasts get regular stimulation, particularly during the newborn period when the mother’s milk supply is being established. That’s why babies cluster feed. Another reason, as I mentioned before, is that babies’ tiny stomachs can only hold small quantities, they empty fast and need refilling frequently, whatever their feeding method, but especially when breastfed. However the book is willing to ignore this important physiological fact and seek to ‘train’ babies like they’re competing for Crufts. So what other fact about babies’ bodies is it willing to ignore?

How about babies’ sucking techniques:

“Some parents worry that if a very young baby gets a pacifier, it might promote a bad sucking style and lead to breastfeeding problems. Usually, these worries are unfounded. There are many, many examples of babies whose technique for latching on to the breast actually improves after they start to use a pacifier” (page 48).

Refusing to acknowledge the risk of nipple confusion is a common sentiment amongst health professionals. It’s therefore unsurprising that the author of this book calls herself a ‘clinical nurse specialist’. Contrary to the author’s stance, there is no reason to believe that a babies’ latch should improve after offering a pacifier, and every reason to believe that it would deteriorate. A pacifier is a silicone replica of a bottle teat. It’s understandable that the author would champion pacifiers, given the goal of this book – to get babies to be quiet and stop disturbing their parents. However the author’s advice has the unspoken side-effect of sabotaging breastfeeding. It’s worth mentioning that the photos which accompany this advice show a *newborn* baby crying, then being plugged with a pacifier. The text also refers to “very young” babies.

Later in the book, the pro-pacifier agenda is pushed again:

“If he is breastfeeding, he will start to regard your breast as a pacifier. Being seen as a pacifier is not an appealing fate over the long term” (page 85).

If you think about it, all parents – whether breast feeders or formula feeders, female or male – are pacifiers. It’s a parent’s job, particularly when their children are in babyhood, to pacify their children. This is no bad thing. Soothing and comforting an infant strengthens the bond between parent and child. So even if a nursing mother were used as a pacifier by her baby, this is a positive process of attachment, not the fate worse than hell that this author assumes. Breastfeeding is not just about food – it’s also warmth, closeness, reassurance, comfort, healing, love… a fact the author of this book is unprepared to acknowledge. This is particularly evident in the author’s response to the next mother’s Q&A:

“Q: We’re doing the controlled crying technique and have found that my daughter’s naps have improved a lot. We lay her down and sit with her. However the process takes longer if just I sit with her; then she tosses and turns and cries more” (Page 109)

The reply begins with:

“A: Like most babies, and particularly breastfed ones, your baby makes more demands of her mother” (page 109).

It is not explained exactly why a baby seeking comfort from its mother is a bad thing. It appears the author has a major thong-wedgie over attachment parenting. So, when you turn the page and read that the next parent seeking advice is a mother whom co-sleeps and feeds on demand, you can hear the pantie-elastic snap:

“Q: Our son is eight months old and sleeping in our bed. He breastfeeds whenever he wants, which is quite often. It would be okay if he fell asleep in between feeds, but instead he’s always on the move. He’s taken over almost the whole bed. We thought this might be a good time to try and improve the sleep situation. Can you give us some advice?” (page 112).

Can she!! But of course! The author is more than happy to oblige with the advice. I can’t promise much of it will be sane:

“A: When dealing with very active and headstrong babies, gentleness often fails. When dealing with a determined baby, you have to be very determined yourself and give simple, clear, messages. Don’t let your son see you until you breastfeed him in the morning (outside the bedroom). Then, after his morning feed, he needs to stay awake for 2.5 hours before taking a nap. He needs to go outside to play once a day after one of his naps. I would not breastfeed him just before sleep. You say goodnight to him and Daddy, and leave the house at 7.30pm” (page 112-113).

More advice includes:

“As you yourselves realise, breastfeeding plays a big role in your current problems. Your baby is now too old to learn to breastfeed just once during the night, so you will have to discontinue all night feeds. It is easier for a baby to learn to stop breastfeeding completely at night than to learn to feed just once or twice” (page 120)

“Keep in mind that you’re not giving your son to a stranger, but to his father, and getting through the night together, without breast milk, will strengthen the attachment between the two of them. It’s best if you can stay somewhere else for two or three nights while this adjustment is taking place” (page 121).

“Father should sit by the door in the bedroom and act as if he neither hears nor sees what his son is doing or asking for” (page 131).

Next, we’re treated to a follow-up letter written by the same mother, and you can’t help but feel great sorrow for her poor baby:

“Thank you for your very precise advice. We’re a week into the new approach now. There were very loud protests the first evening our son was alone with his father and he didn’t want to back down, but his father put in his headphones to listen to music, and sat calmly. On the second evening there was some improvement. Since then he has made progress every evening, until last night when he screamed again for half an hour but then slept through the whole night” (page 114).

As you read that, you can almost hear the poor child’s spirit being crushed. This baby is still young – so young in fact, that it has spent more time in the womb than it has yet to spend in the world. His cry is a form of communication. When his father does not respond to his cries, it lets the baby know that his communication is not important. How soul-destroying.

Despite describing what is basically child neglect, the book encourages the parents to continue, and even to detach further by suggesting that the father go out of sight. Also, it’s not explained why the baby must play outside after a particular nap or why he needs to stay awake for a set time period. Nor is it explained what the parents should do if their baby begins dozing off before that time period is up (match sticks under the eye lids perhaps?) Also precisely why the mother must leave the house remains a mystery, presumably it’s to appease the author’s fetish with distancing mother and child. Think of it as de-attachment parenting.

Other information the book leaves unsaid includes information on the dangers of formula-use. For example, page 52 helpfully states:

“Sleep problems can arise in a baby who has repeated ear infections”.

However the text fails to mention that formula-use increases the risk of babies getting repeated ear infections. This information would indeed be helpful, but it is omitted because such information would undermine the book’s whole ‘formula feeding equals better sleep’ agenda.

If this wasn’t concerning enough, in the “Starting Solids” section, the book then hints that mothers should introduce solids earlier than recommendations maintain:

“The current recommendation is that babies should be given only milk until the age of six months, but it’s important to be flexible to meet your baby’s needs” (page 104).

Sadly, this isn’t the only dodgy weaning-related advice. In the same section, the book recommends that:

“When adding a third solid feed to your baby’s diet, make this in the afternoon if you are breastfeeding and in the morning if you are bottlefeeding. The reason for the difference is that it will help keep your milk production if your baby gets only breast milk in the mornings. You will have a lot of milk when you wake up and can readily put your baby to your breast for the first two morning feeds” (page 104).

This is nonsensical. A mother’s breastmilk supply is naturally low in the evenings, so this is the time of day when she needs more breast stimulation, not less. By giving more solids at this time of day rather than earlier, the baby will be get full and so suckle at the breast less causing a drop in milk supply. There is no reason for the arbitrary distinction between breastfed and formulafed babies with regards to how solids should be introduced.

Yet this book is full of arbitrary advice, which is given, paradoxly, under the premise of making life easier for parents. However when you read the advice, you discover that a lot of it is illogical and unduly complex; not to mention heartless. For instance, a glaring consequence of not being child-led is that the author has to devise elaborate instructions on when, how, and where, to feed:

“Morning feeds can be confusing for babies. If you have recently stopped feeding your baby at night, it is important that you feed her outside her bedroom in the morning. If you feed your baby in her bedroom in the morning and she drops off to sleep afterwards, she might think of it as a night-time feed” (page 106).

When it comes to separation anxiety (which generally occurs around 9 months) the book handles it the same way it handles every other developmental milestone: with a sledgehammer of not-giving-a-fuck:

“Separation anxiety can start to disturb a baby’s night-time sleep. In such cases, your baby will start to cry in his sleep as if he is scared. We don’t know why a baby starts to do this, but a likely explanation is that he is dreaming about what he experienced during the day or other things that are on his mind. You need to be sure not to do too much for your baby when this happens. Always start by waiting for a moment to see whether your baby stops crying on his own. He needs someone nearby, but no more than that. He doesn’t need to be rocked, given something to drink or any other extra service” (page 117).

The next developmental milestone (learning to stand) is approached by all the delicacy of a monster truck:

“When your baby is put to bed for the night, he may stand up straight away, showing off his new skill. Sometimes it will work to hold your baby down for a moment to get him to fall asleep” (page 118).

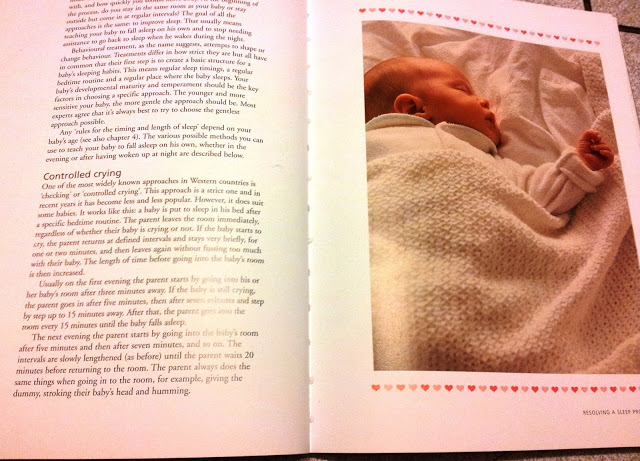

No, you haven’t just read an excerpt from A Child Called It. This is real parenting advice, given in a parenting manual – and this book was published in 2012. In a nutshell, this book essentially teaches parents how to break their baby’s will. Gah, it’s time to move onto another book. From rough-handling to a rough guide, next up it’s…

The Rough Guide to Babies & Toddlers

Kaz Cooke

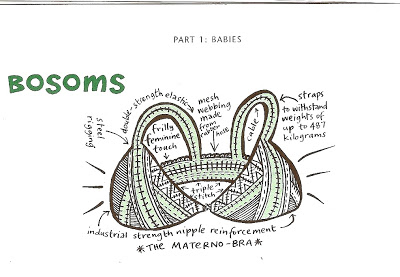

Before I start explaining why this book should be turned into pulp, I’d like to point out that it has sporadic moments of genuine humour. For instance:

“Get an electric breastpump. The machine will make a noise (sort of a cross between a sucking noise and a vibrator, from memory, but that can’t be right – you’d sound like a porn movie)” (page 80).

Ho ho. If you opened the book at that point, you’d be laughing. However as you turn the pages, the sound of laughter swiftly turns into the sound of tutting, intakes of breath and sighing; with the expression on your face resembling a cat’s backside. It’s no surprise that the author is a fan of Gina Ford (she recommends Ford’s books on page 127).

At the start, the book wastes no time in setting the scene for what is to come:

“Although this book is pro-kid, it is also very much on the side of parents and carers” (page 4)

No shit.

Take this piece of advice for example:

“It’s always best to let sleeping babies lie” (page 37).

Best for who? The parents? – certainly. The baby? – not so much, particularly when the baby is very young. A newborn can be so exhausted by the transition from womb to world, that they sleep through their body’s signals to feed. Not only is this dangerous to the newborn, but it is risky to the mother’s milk supply. Yet the book reiterates the same instructions later on:

“If the baby’s asleep, they probably want to be. Certainly never wake a sleeping baby at 2am for their usual feed” (page 131).

If starving your baby isn’t your thing, the book offers the following reassuring advice: put your head in the sand and get someone else to starve them.

“Sleeping through can be encouraged by having a non-lactating person go in to the baby to try to settle them without a feed” (page 133).

Building on this stance, the book suggests adopting a feeding schedule right from the start:

“Your aim would be to feed the baby every three to four hours during the day and when they wake and cry during the night – unless they wake every hour or two, in which case they may just need a rock back to sleep” (page 63).

It’s a fact that demand feeding is the most natural and successful approach to breastfeeding, particularly when it is adopted during the night. Yet demand feeding is not suggested at any point in this 564-page doorstop of a book. Why? My guess is that it is because demand feeding is inconvenient to parents, and particularly to formula feeding parents. This isn’t simply a textbook case of omitting information, the book actually critizises and ridicules demand feeding:

“Although breastfeeding as often as you like in the first weeks will help you build up a constant, replenishing supply of milk, it will leave you a zombie if you wake up every couple of hours to feed the baby. Try to give a complete feed at intervals of three to four hours rather than get the baby used to snacking or top-ups every two hours… Try not to feed every two hours as a regular habit. Be aware that you can get yourself into a vicious circle of feeding your baby little bits too often: you’ll need to gradually extend the time between breastfeeds. I finally worked out my baby wanted a feed pretty much exactly every four hours – which is the case for most babies” (page 63).

In fact, when your baby reaches the ripe old age of 9 months (positively geriatric!) the book believes he should only have 3 breastfeeds per 24 hour period! (page 158).

If this wasn’t bad enough, the book goes from shit to shittier with extra shit, when it prescribes an arbitrary time limit for breastfeeds:

“Eventually you’ll probably be feeding only seven to ten minutes on each breast” (page 64).

Presumably many babies have yet to receive this memo; either that or they are deviant little sods.

“Eighty to ninety percent of milk volume goes in in the first four minutes on each breast” (page 69).

How the heck did she figure this one out? This sentence implies that if your baby feeds for longer than four minutes(!), they are doing so unnecessarily. The book fails to cite where the statistic originates from, presumably it comes from that hefty, over-cited peer-reviewed journal they call Fantasy Statistics. That’ll be the same source that the following came from:

“Anecdotal evidence suggests that older moms, especially those over 40, may have difficulty with supplying enough milk. At this age the reproductive system is winding down and the body produces fewer eggs, so it makes sense” (page 70).

No, it doesn’t ‘make sense’ at all. The book seems fond of anecdotal evidence, but I’ll stick with fact: Lactation is not reliant on a functioning reproductive system. Infertile adoptive mothers can breastfeed. Post-menopausal grandmothers can even breastfeed. Lactation and fertility are not linked in the way the book maintains.

More anecdotal evidence abound when the book broaches the topic of breastfeeding twins:

“If you don’t want to do it, here’s official permission: you don’t have to. Anecdotal evidence suggests moms with twins usually give up in the first couple of months or get the hang of it and go on to feed for a year or more” (page 83)

Geee thanks for your official permission. I’m not sure what mother would abandon breastfeeding based on permission given in an amature childcare book. Perhaps the type of mother who gives the following reason:

“Basically I needed to have my body back” (page 90).

This mother sounds dim. She is going from using her breasts to feed her baby, to using her hands (still her body, I’m sure you’ll agree) to feed her baby. She would probably follow this advice on so-called ‘fast weaning’:

“If you have to wean immediately or relatively quickly (over four of five days) for any reason you may spend a couple of days with rock-hard bosoms. Wear a one-size-too small sports bra to ‘bind’ them” (page 87).

…and get a one-stop ticket to Mastitisville! Breast binding can cause breast damage, blocked ducts, infection, interference with breathing and is very painful. It was mainly practiced in the 1940s and has no place in a modern childcare manual. Endurance of breast binding is just one of a catalogue of burdens this book associates with breastfeeding. Another includes the commonly-quoted suggestion favoured by diet police:

“Eat as well and heartily as you can, particularly if you’re breastfeeding. Special breastfeeding or ‘women’s vitamins’ are probably a good idea” (page 48).

Yeah that’s a good idea – if you’re Donald Trump. However for those people who don’t have money to burn, vitamin supplements are unnecessary. This is even true for mothers who are eating for three during tandem nursing, or while breastfeeding during pregnancy! The same goes for flushing your kidneys with water every second minute:

“You need to drink a lot during the day if breastfeeding” (page 65).

So, living perched on the toilet because you’ve drank so much water is good; but farting a lot? Apparently, this is very bad:

“For lunch in hospital they served cabbage and I chose not to eat it because I’d been told that it caused problems with gas in babies: mine was the only baby in the ward not screaming during the night and I had a midwife ask me what on earth I had done to have the only angelic baby on the ward. When I told her she was amazed. I found the following to cause problems: coleslaw, broccoli, onion, cherries, kidney beans, spicy food” (page 76).

So if you have farty-pants, your baby will have a farty-diaper and be very upset. This assumption bares no credence to medical or anatomical fact. Rather, gas is produced when bacteria in the intestine interact with the intestinal fiber. Neither gas or fiber can pass into the bloodstream, or into your breastmilk, even when your stomach is gassy. So fart all you like. Hell, go ahead and fart the hospital down. There’s no need to burden your diet with restrictions.

On the topic of unnecessary burdens, remember the mammoth list of ‘necessary breastfeeding equipment’ suggested by a book in Part Two of this series? Well that list doesn’t even hold a candle to the following one. Aside from the usual breast pads, nursing bras, breast pump, and those ‘women’s vitamins’ I mentioned earlier, this book lists the following as ‘essential’ breastfeeding kit:

- “A spare top and bra and spare breast pads in your bag at all times in case you leak those big, tell-tale wet circles on your front.

- Pillows to help you support your baby and your back.

- Hot wheat-filled fabric packs (many are designed for microwave heating) to help the milk come in (or use cold to stop your breasts becoming engorged)” (page 66)

Did you hear that people? You simply ‘need’ a wheat filled sack, or else you had better hang up that nursing bra and slump off to the formula isle.

Along with your wheat filled sack, other equipment you will need include one of those over-priced, cumbersome, eyesore rocking chairs:

“Choose a rocking chair or armchair as your breastfeeding HQ. Next to the baby’s bed is perfect, especially for middle of the night feeds” (page 65).

If the thought of arching over a baby in a cold armchair in the middle of the night doesn’t get you questioning your breastfeeding commitment, perhaps the next argument will get the ball rolling. It includes a list of ‘possible drawbacks to breastfeeding’; the most notable of which is:

“You get short-term memory loss, extreme fatigue and other symptoms such as putting the car keys in the toaster” (page 58).

And this doesn’t happen to formula feeding mothers? In fact, studies show that formula feeding parents have less sleep and their sleep is of poorer quality; therefore they are more prone to fatigue (see here). This book’s laughable presentation of fiction is followed up by an even more absurd list (the book has a fetish for lists) titled: “A Wish List For Easy Breastfeeding”. The list includes “as much rest as possible”, “a healthy diet”, “lots of fluids- but not coffee, tea or gin”, and the pier de resistance:

“Luck: you need to be one of the people who can breastfeed” (page 73).

The book doesn’t mention that only 2% of women can’t breastfeed; instead it leaves the threat of being ‘unlucky’ lingering arbitrarily in the air, like that fart in the conference room I was telling you about. Maybe you’ll fall victim, maybe you won’t. Even if you’re aware of the 2% statistic, the book then gives you a list of scenarios which will prevent you from being successful at breastfeeding (I feel like Santa Fucking Clause reading all these damn lists):

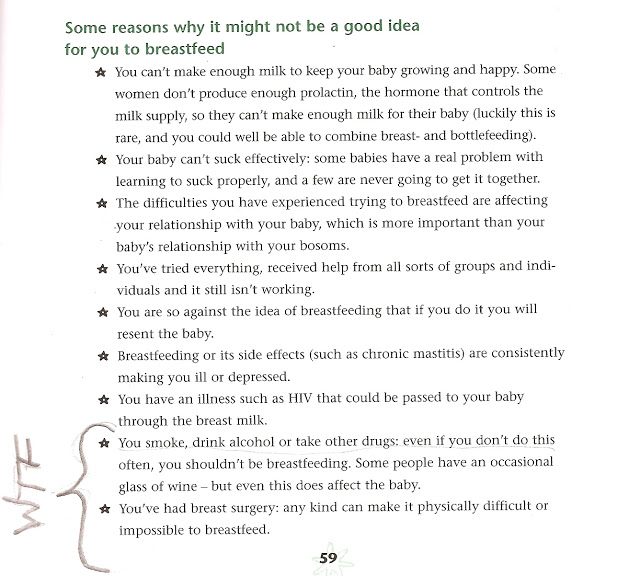

“Some reasons why it might not be a good idea for you to breastfeed”.

The list is longer than is medically or sanely necessary, and speaks for itself:

Wait. At least it doesn’t suggest that you shouldn’t breastfeeding in public.

“It’s possibly best for everyone in the first few weeks if you leave a crowded room so that you can concentrate fully on breastfeeding” (page 64).

Oh.

“If you’re out and need to feed your baby, go to a large mall or department store and use their ladies’ or mothers’ room” (page 66).

Okay, okay, we get the point. Our baps are well and truly banished to the broom cupboard.

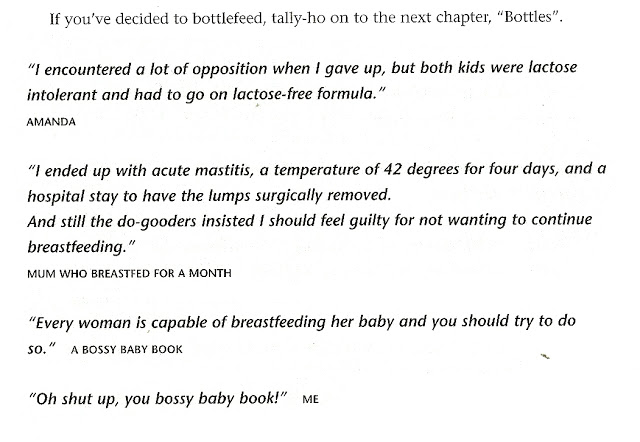

It’s worthy to note that there is no list titled: “Some reasons why it might not be a good idea for you to formula feed”. Perhaps this is because the publisher set a word limit for this book. Nonetheless, the book finds space to squeeze in some sob stories from failed breastfeeders:

It reads like The Alpha Parent Facebook Page after an onslaught of DFF trolls, rather than a parenting manual. After dismissing the notion that a mother should try to breastfeed, the book then expands on its defeatist “breastfeeding is no big deal” mantra:

“The first month or so will always be hardest. Expect some hurdles and know that you’ll usually be able to get over them. If you can’t, there’s the bottle, so don’t panic” (page 62).

Dangling a bottle like a carrot on a string in front of struggling mothers; who else does that? Ahhh yes, multi-billion dollar corporations – the masters of breastfeeding sabotage. Whilst this book doesn’t quite measure up to the insidiousness of formula companies, it’s clear the author gets her inspiration (and possibly her Carribbean holidays) from them. For instance, a fact of life is that perseverance is key to breastfeeding, yet this book bends over backwards to deter perseverance:

“The problem with perseverance is that when you’re in the middle of a difficult time, every hour seems to drag and every feed can bring new tension and anticipation of pain and trouble” (page 71).

How optimistic! What a glowing appraisal of breastfeeding! It’s a good job this book has a “Getting Help with Breastfeeding Section”. Shame it lists various sources of support then proceeds to critique them in a needlessly unforgiving manner. Check out its description of La Leche League for example:

“The La Leche League is an international charity aiming to help moms breastfeed, with mother-to-mother support and encouragement, and to vigorously promote breastfeeding. While its campaigning function has undoubtedly helped to make strides in international policy, if you’re not convinced of your personal growth through breastfeeding then its helpline may not be the best for you” (page 78).

No more is said about the folks at LLL. We are simply left with the feeling that we ought not to phone them because we don’t fit the vague prerequisite of ‘being convinced by our personal growth’, whatever that means. Perhaps it’s the book’s way of saying, ‘if you’re not truly dedicated to breastfeeding, don’t phone LLL’, in which case this advice should be applied to every helpline.

And thus ends the breastfeeding section of the book. Good riddance. The next chapter is called “Bottles”, although it only looks at formula feeding.

The chapter begins with the following opener:

“If you decide to bottlefeed, for whatever good reason, it’s important not to feel guilty about it” (page 95).

Well if the mother wasn’t feeling guilty about it, she probably is now. Good job author lady!

Then the book debunks a few pro-breastfeeding studies, spouts a couple of sob stories, the usual jazz. An orchestra of violins play in unison. Then the author chirps:

“Many breastfed children have allergies and asthma, and many bottlefed kids are absolutely brilliant” (page 96).

Yeah and many babies who are exposed to daily second-hand smoke aren’t huffing and puffing around their baby gyms. Still doesn’t make it right. Imagine, if you will, how bad the breastfed children’s allergies would have been if their body had endured the additional onslaught of formula.

It will come as no surprise that this book has a selective approach to communicating information on formula. It’s very hot on presenting the so-called positives, but shy on the risks. For instance, the ‘anti-SIDS checklist’ (page 40) has no mention that formula-feeding increases the risk of SIDS. Not a sausage.

The ‘Bottles’ chapter has a big phat list (YES! a LISSSSSST! Can you believe it!) entitled: “Good points about bottlefeeding” (page 96). When reading it, you find yourself waiting for an almighty punchline, but it never comes, because this, my friends, is intended to look like a factual list. Highlights include:

“The kid always gets the same thing (breast milk on the other hand, varies in quality and taste according to a mum’s health and diet).”

This is true. Formula fed kids get the same meal – at every meal. The book implies that this is a good thing. Can you imagine any other context in which we would feed our children the same, bland, artificial concoction at every single meal – morning, noon and night, for months on end? We wouldn’t even do this to dogs. At least Pedigree Chum comes in a range of flavours. A breastfed baby, on the other hand, enjoys tastes as varied as our own, thus making them less fussy as they grow older. Anyway, back to this so-called list of positives to bottlefeeding:

“Someone else can feed the baby and enjoy the loving bond and eye contact”.

Yup, because you can’t have eye contact with a baby unless you’re holding a rubber teat in its mouth – go figure!

“Your body is now your own again”.

This is the same scenario for the breastfeeding mother. The only difference is that she uses her breasts to feed her baby, whilst a bottlefeeding mother uses her hands to feed her baby. Either way, you need to sit and feed the baby. Sorry to break that to you. Life’s a bitch.

Then we have this monstrosity of a paragraph:

“Many people who fear a lack of bonding when forced to give up breastfeeding are thrilled to find that, in the absence of stress and the faff about faulty breastfeeding, bottlefeeding is a tender time that can be spent quietly enjoying the moment, free from pain or worry” (page 97).

…. until of course, your formula fed baby regurgitates their entire meal on your favourite black jeans, followed by screaming for an hour with colic, before passing a steaming, nutty, repugnant formula poop. Kinda spoils the moment.

Notice the words used in this short paragraph. In just one sentence, breastfeeding is associated with the words: stress, faff, and faulty; whereas bottlefeeding is associated with: tender, enjoyment, pain-free, worry-free. Going by this paragraph, it sounds like the author fell down Alice’s rabbit hole and is viewing the world in reverse.

To build upon the view of breastfeeding as faulty, the book quotes a mother simply referred to as ‘Amy’:

“I didn’t have enough milk for my premmie baby and I was under a lot of pressure from health-care workers for him to put on weight. After realizing that he wasn’t thriving at 12 weeks I tried a bottle on him and he looked at me with absolute marvel that I had finally given him a decent meal” (page 97).

How was Amy sure that she did not have enough milk? What techniques did Amy try to stimulate her supply? What support did she seek? Was her baby in otherwise good health? We will never know the answers to these questions. The book doesn’t say. It is statistically likely that Amy could have successfully breastfed her baby, and as a premature baby, he needed her brastmilk even moreso.

Another poor sod with a premature baby tells her tale of woe:

“My firstborn was a premmie and couldn’t suck. My milk didn’t even come in” (page 103)

Still, I’m sure these mothers will be pacified by the following list (a list you say?) titled, “Things you get from bottlefeeding as much as from breastfeeding”. It’s a relatively short list. Let’s look at each item in turn:

“The baby enjoys the sucking reflex”.

True. However a baby at the breast can engage in non-nutritive sucking (i.e. enjoy the sucking reflex without having to consume milk). A bottlefed baby, on the other hand, gets a mouthful of milk with each suck on the teat, consequently overfeeding themselves, stretching their stomachs, when all they wanted was comfort.

“Bonding with your baby”.

Yes you can bond while formula feeding – sans the naturally-occurring bonding hormones experienced by mother and baby via breastfeeding. When a baby breastfeeds, because of the release of oxytocin, he learns to associate his mother with all kinds of extra good feelings.

“The feeling that you’re sustaining your baby”.

Well no, you aren’t sustaining your baby, are you? – Similac, Cow & Gate and friends are. You’re just the delivery guy.

“The knowledge that you’re doing your best for your baby and making sure they’re as healthy as possible”.

Lie detector going through the roof with this one!

The book even manages to make formula companies look angelic, by turning their profit-hungry motivation into some kind of drive for scientific advancement:

“The important thing to know is that there are plenty of people who make squerzillions of dollars out of formula, the upside of which is that they have a lot of employees working for their companies trying to make the best formula and get it as nutritionally close to breast milk as they can, with some extras such as iron supplements”(page 98).

The amount of money formula companies’ put into research and development is dwarfed by the money they pump into their marketing budget (persuading parents to feed their precious offspring sub-standard crap from cans takes a lot of sophisticated coercion). Consequently, parents pick up the bill for this hyper-marketing through the inflated prices of formula. Does the book mention this? That’s a rhetorical question, obviously.

As for the ‘extras’, I concede, there is certainly a lot of extra crap in formula that you won’t find in breastmilk – again, this is for marketing rather than nutritional purposes. Each formula company tries to pwn the rest by adding more and more fictional pixie-dust to the cauldron. Whereas every ingredient in breast milk was created by nature to serve a purpose. Does the book mention this? Again, rhetorical.

In appears that, in an effort to lick the wounds of Defensive Formula Feeders, the book kneels at their crotch, painting a euphoric image of bottlefeeding, which at times, is nothing short of pure fantasy. Take this assertion from page 99 for example:

“Babies on properly prepared formula are never too fat”.

Whatevs. You can follow WHO preparation guidelines to the latter and still overfeed your kid with a bottle. As I said above, babies like to comfort suck, but they cannot do so at a bottle without receiving a constant waterfall of milk into their stomach. Whereas at the breast they can regulate their suckling so that no milk is released if they wish. Not to mention the imbalance of proteins in formula programmes a baby’s body for excessive weight gain.In fact, overfeeding and hyper-protein content are some of the reasons that formula fed babies have been observed to sleep longer. They’re all sluggish and bloated from rich Christmas-banquet-sized meals, as illustrated by this comment:

“I found my baby slept better through the night as the formula is thicker and fills tummies better” (page 104).

Read: it forms a curd in the baby’s stomach. Nice. This curd sloshes about for hours in your baby’s tummy, stretching it, producing pain and wind. Consequently, and not unlike the average person after Christmas lunch, baby has to sleep off the effects. He’s too uncomfortable to do anything else.

This inclination towards rest is met with hoots and hollars from formula fed parents, who revel in their liberated evenings.

“The more pressure I put on myself to breastfeed the worse I felt, and in the end I put my babies on formula and never looked back” (page 106).

You go sista!! Nevermind about the risk of allergies, gut problems, infections, cancer and SIDS. As long as you have your precious pee-pees. Speaking of sleep, it’s time for another ‘sleep training’ guide…

The Sensational Baby Sleep Plan

Alison Scott-Wright

The only thing ‘sensational’ about this book is how it ever got to print. A typical dissenting Amazon review tells all:

“The whole attitude and atmosphere to this book made me feel uncomfortable and as a new mother who is exclusively breastfeeding, it was thoroughly depressing and made me quite upset.”

And another:

“As a breastfeeding mother who looked to this book for help I cried when reading this.”

What’s all the fuss about? Let’s take a look. Firstly, the author, Alison (who has no qualifications medically or otherwise) sets the scene for her ‘down-to-earth’ sleeping plan. She uses vague terms such as ‘perfect baby’ and ‘proper family unit’ to undermine government guidelines:

“I am fully aware that the existing government guidelines on feeding and babycare are set out to promote your baby’s health and wellbeing, but they are not always easy either to implement or to stick to. In an ideal world, we would all exclusively breastfeed, not work, stay at home, raise the perfect baby, have a ‘proper’ family unit, masses of help and support, and never be stressed or overtired. As this is not the case for most of us, my plan, although sometimes ‘bending the rules’ a little, is a down-to-earth and sympathetic approach designed to meet the needs of both parents and baby” (page 2).

So she acknowledges that government guidelines exist to promote babies’ health and wellbeing, and then proceeds to say she will be discarding them because they are inconvenient to parents. So far, nothing ground-breaking; Gina Ford has been doing this for years. Then Alison regurgitates another tired-old clique:

“My method is always baby-led and mother-focused, working on the basis that if the mother wasn’t happy then baby wouldn’t be happy either, and vice versa” (page 2).

‘Happy mom – happy baby’ the mating call of the lazy-parent. It is often sung by those who put their own needs first, and want to justify it. Case in point:

“In my view it is better to adopt an approach that can be adapted to your lifestyle than to restrict yourself to a method that you may find difficult to maintain” (page 24).

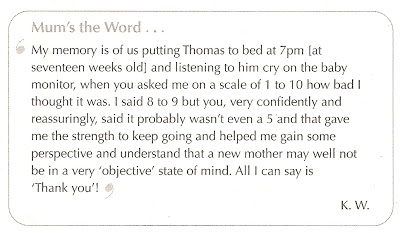

News flash: fuck your lifestyle. Babies take a steaming big dump on your lifestyle the moment they are born till approximately eighteen years of age. A parent who believes she can shoehorn her baby into her existing lifestyle will soon be shoehorning herself into a straightjacket. Yet somehow the ‘happy mom – happy baby’ comfort blankie continues to be a popular fantasy of many. Take the following paragraph for example, which screams “SABOTAGE” in big Disneyland flashing neon lights. Here, a mother speaks of her experience of being advised by Alison:

“My baby was not gaining weight, I was really struggling with breastfeeding and my baby never slept. Alison came round and after much discussion we gave Margot her first bottle of formula. She sucked it down in 1 minute and then fell asleep for 3 hours. It was a beautiful sunny day – the first time I had noticed in 3 weeks. I had a feeling of complete relief and physically felt my shoulders loosen as the tension flooded out of me. I realised that formula feeding was not ‘evil’ and bad, and that, as Alison had said, ‘a happy mom makes a happy baby’. Margot and I have never looked back…Breast is best, but not for everyone!” (page 24).

Sad indeed is the fact that this mother seemingly had her breastfeeding relationship sabotaged by a self-appointed sleep guru with no training in baby-care or anything else. At a time when the mother needed to work on her supply more than ever, formula was given to reduce it further (top ups are also recommended by Alison as an ironic ‘cure’ for supply problems on page 88). This mother obviously set out to breastfeed, yet it seems, was manipulated while she was at her most vulnerable, by someone disguising themselves as support. Sadly, when a mother is feeling exhausted, it is easy for a person with an anti-breastfeeding agenda to exploit the mother’s urge for rest.

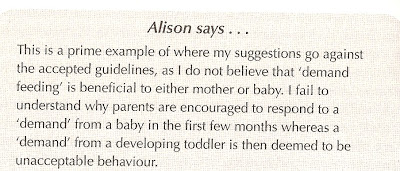

Most pro-formula sentiment rests on the empty promise of rest, so it is no surprise that this book rejects demand-feeding:

“The decision of when to feed has to come from the parent and not the baby. Demand feeding is often unmanageable, as parents cannot take charge of their days but are controlled by the demands of the baby” (page 8).

Even newborns, fresh from the womb apparently should have their hunger cues ignored:

“I advise using my plan from Day 1, or at least starting as early as possible” (page 5).

“Most babies are born nocturnal and it is very important to re-train them within the first few weeks of life” (page 66).

Re-train is an interesting choice of phrase. Babies are not performing circus seals. They are born hard-wired for survival. Re-training them means forcing them to go against their natural biorhythms. These physical, emotional and cognitive cycles are central to your baby’s optimum development, however they have one snag – they tend to be inconvenient to parents, who have different biorhythms. Why are babies’ biorhythms so different from adults? Answer: because babies need to sleep this way. Rather than temporarily alter your adult biorhythms to accommodate your baby’s, Alison suggests forcing these alterations upon your immature and vulnerable newborn. For example:

“Persevere with feeds during the day to ensure that your baby takes enough milk to help him get through the night” (page 64).

Eradicating night feeds during the early months with lead to a botched supply, as I mentioned earlier.

Another part of Alison’s re-training process includes giving your baby a bath every day:

“Always introduce an end-of-day bath and bedtime routine as soon as it is possible to do so” (page 117).

Bathing your baby every day, particularly a young baby, will leave them vulnerable to developing eczema and other dermatological problems. This is because bathing washes away the skin’s naturally protective oils. The risk is exacerbated further when any products are used. Yet many parents are fixated with baths as an integral part of the bedtime routine because they have been influenced by companies such as Johnson & Johnson and by health professionals (who have also been marketed to by Johnson & Johnson).

Next, Alison gives your baby a deadline for sleeping through:

“It has become plain to me that young babies are, on the whole, capable of sleeping through the night by around eight weeks of age” (page 10).

Poor little mites. So that means that by 8 weeks, your baby should have zero night feeds. The book features a letter from a mother whose 10 week old baby failed to receive this memo:

“We have been putting our baby to bed around 7pm since Week 1. He is now ten weeks old and still cries for 10-15 minutes before going to sleep, but then he does sleep all through the night. Is this normal and is there anything we can do?” (page 79).

In Alison’s reply, she dismisses the baby’s evident distress:

“Really there is no such thing as ‘normal’ – all babies are individuals and will display different behaviour patterns. Although he cries, your baby does eventually go to sleep and then sleeps through the night. This indicates that there is little wrong and I would suggest that it is just his way of winding down as he prepares to sleep. It is fairly common behaviour and nothing to worry about. I would advise little or no intervention to try to stop him crying as this may only disturb him, thus prolonging the time it takes him to go to sleep” (page 80).

This baby’s basic biological cues were not being listened to, and his needs were not being met. So he had given up on trying to connect with his caregivers. Alison repeats the same advice to a different parent later in the book:

“It may seem harsh just to put him into bed while he is so upset, but it is often the best thing to do” (page 91).

Alison maintains that you should follow this cruel isolation approach, even when your baby is in unfamiliar surroundings: