You can always count on a ‘Sleep Training’ book to come up with the anti-breastfeeding goods. Lord knows I’ve showcased a few of them. So, not to disappoint, here’s two sheer corkers written by two old codgers!

Solve Your Child’s Sleep Problems

Dr Richard Ferber

In case you live in a cave, the author of this book, Dr Richard Ferber is a quasi-celebrity of the parenting world. In fact, he’s such an idol that his sleep-training methods have been coined “Ferberization” (try saying that after a night out). We’re talking about the dude that created “Controlled Crying” here. More on that later, but first, take a look at the title of his book: ‘Solve Your Child’s Sleep Problems.’ Right from the start Ferber is labelling your baby and turning him into a ‘problem-child’. To his credit, he at least attempts to justify this:

“If your child’s sleep patterns cause a problem for you or for him, then he has a sleep problem” (p8).

Actually, no Ferber; If his sleep patterns cause a problem for his parents, that is technically the parents’ problem. The baby is just being himself.

Pedantism aside, taking a literal approach to what constitutes a problem is in itself problematic because it serves to widen the scope of baby behaviour considered ‘undesirable’. In Ferber’s world, as long as it’s pissing you off, it’s officially a problem, and Ferber is already unbuttoning his shirt revealing an “S” symbol, cape flapping in the wind, spandex, the works. He will save you!

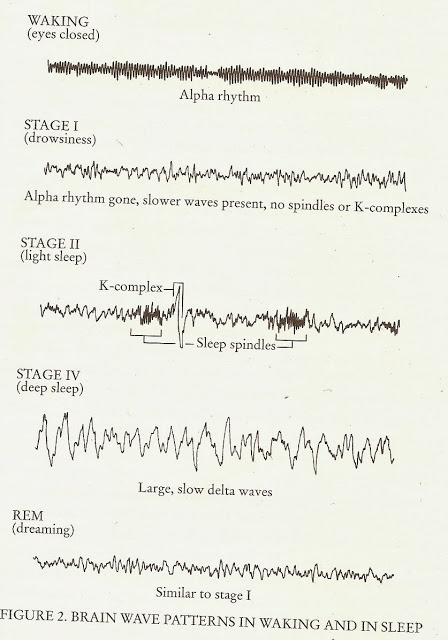

Before I delve into explaining how Ferber intends to save you from your child’s demonic demands, I won’t argue that Ferber doesn’t know his shit. Just look at this impressive array of EEG brain wave scannings that adorn several pages of his book. These wobbly lines illustrate the different stages of sleep: lines close together and you’re buzzing, spread out and you’re dead to the world. Or something like that. What purpose these illustrations serve in this book is anyone’s guess, not that it matters because their presence screams “SCIENCE!!” and parents love a bit of sexy science. However, when you bear in mind that Ferber has zero psychological training, these diagrams, whilst sexy, seem rather impotent.

Lesson 1: No co-sleeping

It should come as little surprise that Ferber’s clinical approach does not lend itself to the intimacy of co-sleeping. In direct opposition to his arch-nemesis Dr Sears, Ferber is adamantly anti- the family bed. His book is littered with clinched codswallop hinting to the often-quoted, seldom-experienced slippery slope: co-sleeping tweenhood…

“Far too many families start co-sleeping early, assuming it will stop on its own at some point, and then find themselves years later with a five-, seven-, ten- or twelve-year-old that they ‘can’t get out of’ their bed” (p43).

Sodding tweens with their glowing ipads, keeping their parents awake at 2am. Wait, in what realm outside David Walliam’s Little Britain does this actually happen? Yet 5 pages later, Ferber is still bashing the family bed. In a section he drolly calls “Co-sleeping: The Endgame”, he maintains that:

“Few child care specialists recommend co-sleeping much past the age of three. When you begin co-sleeping, you should have a plan in mind of how and when you will stop” (p48).

Why does everything need a plan? Why do parents have to specify a date? We don’t ask for set-dates for other milestones (first word, first step, first tooth) because it’s impossible: children are organic and develop at different rates. One child might be ready to sleep on their own at 12 months, another may not be ready until 3 years or more. It’s unreasonable to expect parents to predict when this milestone will occur. Unless naturally, Ferber is talking about forcing the child to meet the milestone. Is he?

Lesson 2: Controlled crying

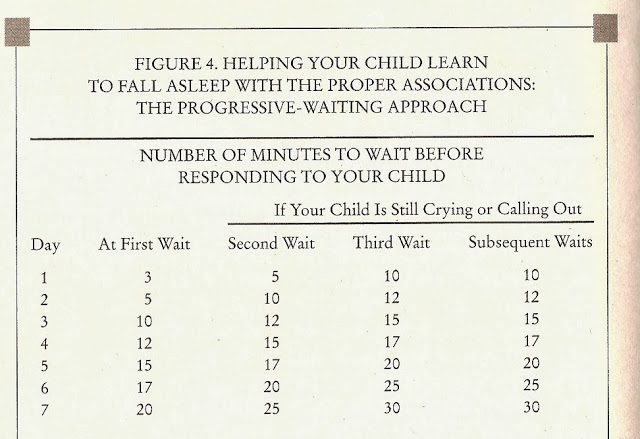

Bingo! Right on schedule, Ferber introduces his universally renowned method of sleep training – ‘Controlled Crying’. Renowned, of course, for all the wrong reasons. His militant approach to forcing babies to sleep involves leaving them to cry for increasingly long periods (see table below).

The reason this method is so well-known is – frankly I’ll admit – because it works. The baby does eventually go to sleep – she cries herself to sleep. It’s Armageddon before then however. If the baby is mobile, to prevent the little blighter escaping from her solitary crib, Ferber suggests barricading her exit:

“If your child will not stay in her room when you leave, then you need to use a boundary of some sort, such as a gate or the door” (p90).

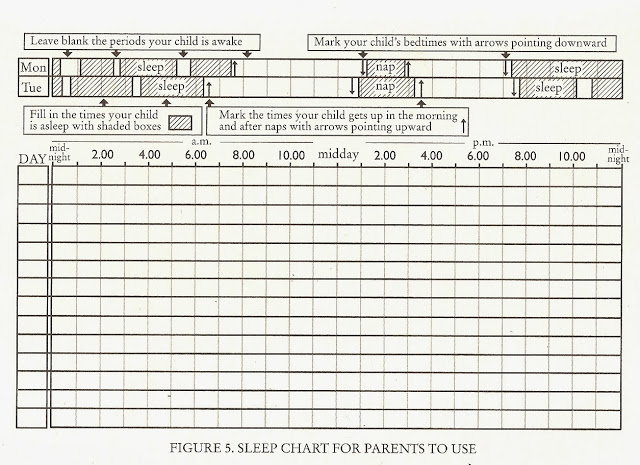

He’s fashioned a chart so you can track your ‘success’:

By creating this sleep training technique, Ferber is demonstrating a huge false assumptions of how young babies’ brains and their neurophysiological development actually work. (Surely as a doctor, you’d think Ferber would know the basics?) His belief in his process of Controlled Crying relies on a certain set of presumptions, the most concerning of all being that tiny babies can form habits and think logically and rationally, just as adults do. Yet the vast majority of a baby’s 100 billion neurons are not yet connected into networks. Consequently, babies simply don’t think like we do. The neocortex, the part of the brain responsible for logical thinking, does not spring properly into life until preschool age. Instead, a baby’s brain is very primal, being focused on survival.

So how does the biology fit with Ferber’s training technique? Fact: a baby’s cry is their first attempt at communicating. Through it, the baby establishes his status as someone who deserves something. When the communication is answered, the baby’s sense of positive entitlement as a person becomes stronger. However when their cry is ignored, this sends the opposite message – that they are not worthwhile. Controlled Crying rightfully has a bad rap because it provides inconsistent messages about self-worth and ultimately leads to insecurity. It’s, quite frankly, an upsetting and traumatic process for all concerned.

Don’t want to use Controlled Crying? Tough! Ferber insists that it’s your own fault you have to use his training technique. In a mammoth chapter titled:

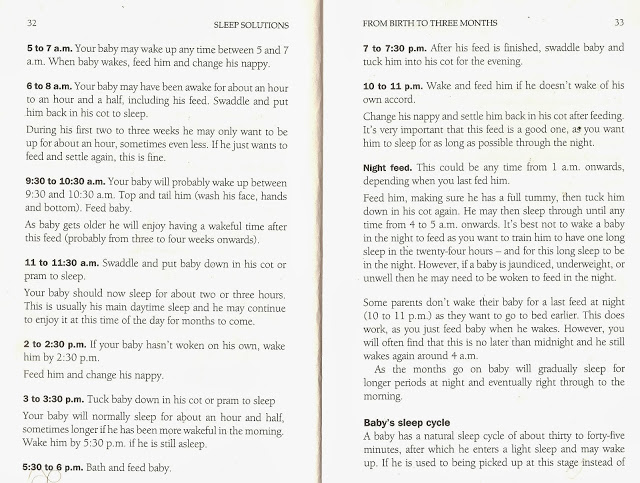

“Feedings During the Night: Another Major Cause of Trouble”

Ferber speaks of:

“sleep disruptions caused by too much feeding at night” (p137).

His instructions are clear: Stop Night Feeding You Snivelling Dweeb Mother! He then provides concise instructions on how to do so (I challenge you to get to the end of the following sentence without rolling your eyes skywards):

“Reduce or eliminate the night-time feedings, thus avoiding your child’s various sleep-disrupting effects and also helping your child learn to get hungry only at reasonable times during the day” (p140).

Reasonable times during the day? Sorry dude, visceral drives, such as hunger and (*whispers it*) sleep, are by their very nature – not reasonable. They are biological cues and don’t bend to logic. Try telling a hungry 3 month old that their need for food is unreasonable. Heck, try telling me in the throes of PMS that I don’t need that Wetherspoons chocolate fudge cake. Go on, but protect your balls!

Actually, ignoring your baby’s hunger drive is precisely what Ferber instructs you to do, by watering down feeds (p147) or by stealth reduction:

“Begin by gradually decreasing the number of night-time feedings or their size, or both” (p141).

Dodgy advice. Studies have shown that decoupling feeding from sleep in infants younger than six months is associated with increased breastfeeding failure. Fancy a slice of breastfeeding failure with your sleep deprivation? Thought not.

And woe betide you actually enjoy nursing your baby through the night (and why shouldn’t you? After all, oxytocin and Prolactin are a sleepy mom’s best friend). If so, Ferber thinks you are a nut-job:

“It is unpleasant and usually unnecessary to nurse or feed a baby hourly throughout the night” (p141).

Put those titties away lady! And while you’re at it, wear an iron chastity bra:

“If you are nursing and your nursing child sleeps in your bed, you may have to be firm when she tries to get at your breast before it is time to nurse. You may even have to get up temporarily and sit by the bed, or even leave the room” (p145).

Yeah, sure, mom could faff on doing that. Or she could just latch her child on and fall back to sleep. Hmmm tough choice.

But wait, I know what you’re thinking – this Ferber dude still isn’t hardcore enough, dammit! Well, have I got a treat for you!…

Sleep Solutions

Rachel Waddielove

Why did the sleep training book cross the road? To rip breastfeeding a new asshole.

I’ve saved the best (read: worst) for last. ‘Sleep Solutions’ is a blatant illustration of breastfeeding sabotage. Indeed, this bad boy makes Ferber look like Newman.

Sleep Solutions is a wolf-in-sheeps-clothing written by a woman called Rachel Waddilove. As well as being blessed with an unfortunate surname, Rachel has an equally annoying penchant for referring to babies in the third person, in a manner not dissimilar to a bossy toddler: ‘Baby doesn’t need to be held. Baby should sleep in his own crib.’

She is also a fan of putting baby to sleep in his pram outside, giving baby a bath every night (eczema trigger anyone?), dispensing Calpol at the slightest cough or twitch, and other outdated dogma.

Also, Rachel is Gina Ford on steroids! Whilst Gina gave the finger to the parenting world with her OCD-scheduling, Rachel sets fire to the parenting world, and then slams it with a wrecking ball, before blasting it into orbit to be inflamed by the sun. Gems of advice include relegating your baby to sleep into another room – the bathroom, no less:

“After a few nights I may move baby into the bathroom, especially if he is a noisy sleeper” (p22).

The bathroom, FFS! His cries will echo off the tiles, and as for the poo spores evaporating from the toilet! Jesus wept!

Lesson 3: Ignore SIDS guidelines

Rachel is also partial to mooning at SIDS guidelines:

“You can move your baby to his own room as soon as you feel ready to let him go. I personally feel that six months is far too long to keep him in your room; baby is disturbed by you and you are disturbed by his little noises in the night. If you are trying to sleep train your baby or toddler they need to be in their own room, as it is impossible to do it with them in the same bedroom as you” (p22).

Separating mother and baby in this way is a cast-iron way to reduce the probability of breastfeeding success. Breastfeeding works the way it is designed to work if you keep your baby close to you, especially in the first few weeks, and let him lead the way. Yet needless to say, in Rachel’s world, such co-sleeping is out:

“Baby should not sleep in bed with you” (p22).

Ironically Rachel cites SIDS risk as a reason not to co-sleep. Yet having blatantly contravened SIDS guidelines by suggesting your baby sleep in another room, she continues to shit on said guidelines, not once:

“Babies may be more comfortable on their sides and usually sleep for longer in this position” (p30).

Not twice:

“If you have him on his side, don’t forget to roll up a small cotton cot blanket and place it behind his back” (p30).

But, three times:

“Many babies will suck a muslin by the time they get to a few months old. You can tie one to the bars of his cot” (p26).

A sure-fire way to suffocate a baby would be to tie material to their crib. Do not do this folks. Not to mention encouraging your child to suck on material will increase the risk of them becoming infected with threadworms. Nice.

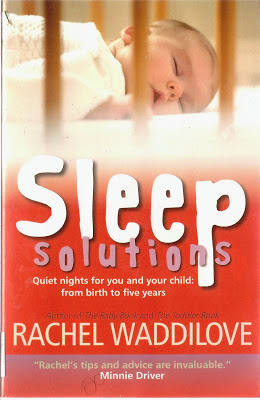

Rachel then takes aggressive scheduling to a new level, with a routine that would make Gina Ford’s never-lactating bosoms swell with pride:

“After about one month. Baby should sleep for about an hour or so after the early morning feed. He should then sleep for two to three hours in the late morning, and again for about one to two hours in the afternoon. He should be in his cot again at about 7pm. After a late feed he should sleep for a longer period until he wakes in the night to be fed. After the night feed he should settle again and sleep until morning” (p31).

This rigid timetable isn’t just unrealistic, it’s downright bonkers! We’re talking about a 1-month-old here people! Newborns have a normally erratic existence because they are adjusting to life sans uterus. Rachel’s three hour gaps between feeds are not compatible with the mechanics of breastfeeding. Nature just isn’t designed to work like this. For a mother, controlling or restricting feeding is likely to lead to engorgement in the short term; in the long term it will cause less milk to be made. For a baby, breastfeeding is more than just food or drink – it also provides him with comfort, company, warmth and security. None of these things can be regulated by the clock, so expecting your newborn to fit into a schedule is illogical and cruel. Every mother, particularly breastfeeding mothers, should watch their babies and not the clock. If you ignore the clock you allow your baby to control his own milk intake and listen to his body’s signals, for both hunger and fullness, which will stand him in good stead for later life, when as an adult he is more able to listen to his body and thus not under or overeat. *and breathe*

Lesson 4: Controlled Crying, take 2

Still not convinced by demand-feeding? Then consider this: rigid, scheduled sleep routines in the early months are associated with three times the risk of behavioural problems at six months and twice the amount of crying as infants with cue-based care (Source: this 2013 study). Newborns need attentive care, yet Rachel advises leaving them to cry:

“Don’t go to him straight away if he doesn’t settle. Many babies can take five to ten minutes to settle themselves. If baby shouts and the shouting gets louder and louder and he is clearly not calming down, go in after ten minutes” (p34).

But wait, it gets worse:

“If your baby is a few weeks old you may need to leave him to have a shout for a bit longer. Sometimes he might take twenty minutes or so to settle. If you know that he is well fed and tired it is better to leave him to settle on his own” (p35).

Babies don’t have any concept of the future. Their survival instincts tell them that their need is urgent and research suggests that if they don’t get a quick response they feel frightened. Trying to fight your baby’s instincts to be fed and held will make him – and you – stressed and miserable. Ain’t nobody got time for that!

Did I tell you it gets worse? Now, multiply that by a hundred:

“If you find it too distressing to listen to baby shout, go somewhere where you can’t hear him, or turn the radio on and try counting to 200 as this may help you to deal with it” (p36).

There’s a reason why parents find it so hard to listen to their baby cry – it’s distressing because crying is nature’s cue to tend to your baby. The tone and pitch of a baby’s cry are biologically designed to herald a response in caregivers. Indeed, infant cries trigger hormonal surges. To ignore a baby’s cry is to ignore nature. It’s the equivalent of divorcing our biological imperative, of denying our humanity. If you think I’m getting needlessly hyperbolic here, recall that we’re talking about newborns. Babies of this age cry to communicate important survival-based needs. Also – and this is heartbreaking – it is not uncommon for babies to get an ear infection in the middle of sleep training (from the congestion caused by the crying) which will make them cry even more.

Advising mothers to ignore the cries of their baby – their newborn no less – is a classic boobie-trap. When a baby is tended to less, they suckle less, and as a result less breast milk is produced and a vicious circle is created. Now for a mini science lesson: breastmilk contains a protein called the Feedback Inhibitor of Lactation (FIL). The amount of FIL is dependent on the amount of milk in the breast and its function is to reduce production when it seems the milk isn’t needed. So if your baby is feeding infrequently, or has a longer than natural gap between feeds, your milk-making cells will respond by slowing down. And only your baby knows what a natural gap feels like.

Lesson 5: Top Up With Formula

Demand feeding prevents the aforementioned vicious circle arising in the first place (not to mention it is recommended by WHO as the ideal way to breastfeed), yet rather than advocate demand feeding, Rachel instructs the exact opposite – topping up:

“Sometimes a baby will feed well but just not settle afterwards. This often happens in the night when he is about two to four weeks old. If you don’t think you have any more milk and he is hungry, give some expressed breast milk in a bottle, or offer him one to two ounces of formula. This may be just what he needs to settle him” (p38).

So, first Rachel tricks mothers into reducing their milk supply via not attending to their babies’ cries; then she reduces their supply further by advocating top-ups. Even if a mother were to use expressed breast milk for the top-up, she puts her newborn at serious risk of nipple confusion.

If the mother is fortunate enough to escape a dip in supply as a result of ignoring her babies’ cries, she will nonetheless believe she has because of Rachel’s vague wording: “if you don’t think you have any more milk and he is hungry…” a top-up “…may just be what he needs to settle him”.

But wait, one minute Rachel is instructing you to top-up if your baby is not sleepy after a feed (above), and then in the same breath she asserts that your baby shouldn’t be sleepy after a feed! Observe:

“Avoid keeping your baby on the breast until he falls asleep and then putting him straight into his crib. This may seem an easy way to settle him when he is little, but by the time he is three to four months old you will find it impossible to settle him in any other way, and you will wish you taught him to settle by himself” (p35).

Codswollop! In reality, breastfeeding is comforting and soothing to a baby – a lovely way to drift off to sleep. Allowing your baby to relax and let go of the breast in his own time is a good thing. He will gradually find ways to settle himself and fall asleep on his own, I assure you, but he doesn’t need to be deprived of his main source of comfort in order to do that.

Rachel’s instructions are five-star sabotaging. But don’t just take my word for it, a few pages later there is a testimonial from one of Rachel’s victims-slash-clients named Nicola. Her statement is worth reproducing in its entirety:

“Henry was about five weeks old when I first got in touch with you. I was beginning to feel desperate, as Henry wasn’t sleeping at all well. He would often only achieve a total of forty-five minutes sleep throughout the entire day. He seemed to be constantly hungry, and with feeds taking forty to fifty minutes each it was almost time for the next feed once I had fed him, changed him, and tried to get him to sleep. The whole household was exhausted and frustrated as we couldn’t work out what we were doing wrong.

We were in a vicious circle. I was so determined to feed on demand that I’d forgotten that crying could also be due to tiredness. It seems so obvious now, but I was in a bit of a newborn/new parent daze. Poor Henry was too tired to feed properly and too hungry to sleep properly. You suggested I top him up with some formula to make his tummy really full and cosy so that he would start sleeping longer and the cycle would be broken. It worked a treat and I soon established a three-hour schedule. Henry became a much more content little boy and I began to feel a lot more confident as a parent.

I also used your great techniques for making Henry feel secure, cosy, and able to sleep. Swaddling him properly in a cotton cellular blanket has proved invaluable” (p45-46).

There it is. Word for word. It reads more like a game of Boobie Trap Bingo than a success story. Formula top-ups – check. Abandoning demand feeding – check. Installing a three-hourly feeding schedule for a newborn – check. Not to mention the blatantly biased and romanticized language used to describe formula feeding: “formula to make his tummy really full and cosy”. And then, as the icing on the malpractice cake, there’s the SIDS swaddling issue. BINGO!

Lesson 6: Train him like a dog

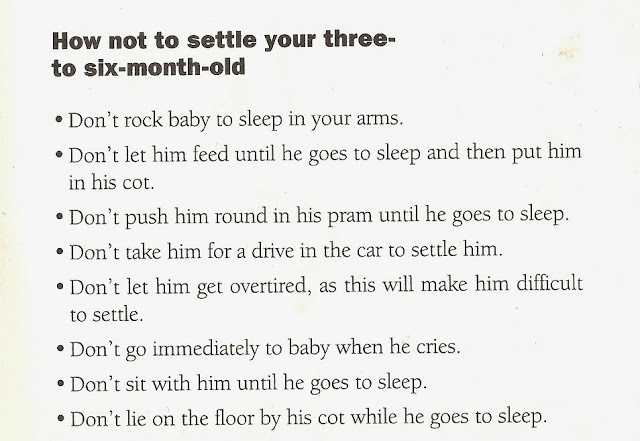

As we say good riddance to the newborn chapter and turn the page, we enter the “Three to six months” chapter, which is basically a rehash of the newborn chapter. Rachel cheerfully reassures us:

“If your baby isn’t sleeping through, don’t worry, it’s not too late to teach him” (p49).

Teach indeed. Babies are not animals to be taught and trained, yet the language becomes more and more canine:

“During the day the trick is to get him to sleep until his next feed time” (p50).

“All babies can be trained to sleep if you know what to do, and you are consistent and persevere. Over all the years I have been helping with sleep training I have never known of a baby or child who has not been trainable. As long as he is fit and healthy he can be trained to sleep” (p64).

Wow, just wow. WTF is up with using language such as ‘tricks’ and ‘trainable’? Babies aren’t auditioning for Crufts! The dog-show dialogue continues:

“I recommend that baby sleeps in his own room by the time he is three months old, particularly if you are trying to sleep train him. In my experience it is almost impossible to train a baby to sleep when he is in the same room as you. His crying can really get to you and the need to pick him up for a bit of peace and quiet can be overwhelming. If baby does share your bedroom because of a lack of space where you live, see if you can borrow a screen, or get an old one in a sale. That will help to screen you off from each other. You may need to use a pacifier to help cut the noise down” (p50).

The sad picture this paints is of babies as inconvenient tyrants rather than young human beings. As a bothersome problem, your baby needs to be separated from you, his parents – preferably by a wall but heck, a screen will do – and then make sure you plug his facial-orifice to mute his existence. That way, if he doesn’t die of SIDS from sleeping on his own, at least you won’t hear him.

Lesson 7: Discount separation anxiety

“Baby needs to go in his own crib and get used to sleeping on his own” (p51).

No shit. You mentioned that before Rachel. But won’t my baby get separation anxiety? He’s still a noob to the world after all.

“Some people worry that their baby will suffer from separation anxiety if they put him in his own crib and room. However, babies who have their cribs and rooms don’t generally suffer from separation anxiety. If they do, there are usually other underlying family problems” (p51).

Say WHAT? Separation anxiety is not a red flag, it’s a normal developmental stage. Did Rachel fall out the stupid tree and hit every branch on the way down?! I’m beginning to wonder if she even knows what separation anxiety actually is. Evidently not if the following paragraph is anything to go by:

“Your baby should have his own crib and not sleep in your bed with you. Children who share a parent’s bed may become so attached to a parent that they develop behavioural issues and suffer real separation anxiety. This is very unfair on the child and can be very distressing for you” (p100).

Uhh…wait, what? Co-sleeping creates separation anxiety? What in fresh hell is Rachel talking about? Can you hear that groaning sound? That’s Dr Sears keeling over.

Then, just when you think Rachel can’t possibly spout any pish more ludicrous than the aforementioned, she gushes:

“A lot of babies will settle better on their tummies by three months” (p52).

No mention of this being a SIDS risk. *sigh* So far, this book is essentially a manual on how not to parent. Yet there is one common ingredient thus far missing from Rachel’s catalogue of faulty advice – premature introduction of solids. Oh look, here it comes now:

Lesson 8: Introduce solids early

“The main reason for babies not settling or waking early for feeds is that they are hungry, so this does need to be looked at first. The current advice is not to start giving your baby solids until he is six months old. For most babies this is not early enough” (p57).

WTF. Here, Rachel is suggesting that clearly established nutritional guidelines don’t apply to “most babies”. Rachel, are you on glue?! Most babies’ digestive and immune systems are not able to cope with anything other than breastmilk or at a pinch – formula – before six months. If they are given other foods earlier than this they may not be able to digest them fully and, if they are breastfed, they will take less milk causing supply issues.

“If your baby is not sleeping after having previously been settled, or if he is waking earlier and earlier in the morning, he probably needs some solid food in his tummy” (p57).

Baby suddenly waking in the night? Sounds like a perfectly normal growth spurt to me, a signal for more milk, not an invitation for mom to crack out the baby rice. If your four-month-old really is hungry she will get more nourishment from extra breastfeeds than she would from solids.

The sceptic in me ponders Rachel’s motives for suggesting that solids are introduced significantly earlier than established guidelines. The plot thickens when she plugs one of her previous books and also Annabel Carmel’s recipe book (both on p57).

Lesson 9: Perfect your ignoring technique

Next, we are treated to a reiteration of Rachel’s tips for ignoring your baby’s cries:

“You need to survive and get through the disturbance of a crying baby. If he shouts a lot during the day it is easier to deal with than when he shouts at night. During the day you can shut the door, go and do something else, and try not to listen. Turn the baby monitor down or off. You can go into the garden and count to 200. Sit down and listen to some soothing music or make a cake if you like baking” (p65).

Yup, this book is advocating neglect on a grand scale. Make a fucking cake? What the actual hell. Just in case you need reminding of the age of child we’re talking about here, Rachel emphasises:

“A three-month-old baby is not too young for the controlled crying method” (p66).

“By the time your baby is three months old he should be able to sleep through the night from about 10pm to between 6 and 7am the next morning” (p69).

This advice is nuttier than a squirrel’s ass. Not only is sleeping through the night at this age bad news for your baby (babies are not supposed to sleep too deeply – SIDS risk); it’s also bad news for your milk supply. Optimum breastfeeding relies on you and your baby staying in sync 24 hours a day. The irony is that the advice in Rachel’s book, which is designed to make night time easier for parents, will ultimately have the opposite effect. Shoe-horning babies into unnatural behaviour skews parental expectations. Night feeds are easier for everyone concerned if you don’t expect your baby to sleep right through…

Lesson 10: Don’t pick up your baby

Yet, Rachel persists with the tired rhetoric that if you heed to your natural instincts you will spoil your baby:

…“if you do this every time, he will fall into bad habits and expect to be picked up every time he cries” (p66).

Folks, tending to your baby is not about allowing your baby to rule your life; it’s about adjusting your life to include your baby. Rest assured, your little one will eventually eat and sleep at conventional times, but not yet. Controlled crying is unnatural. It puts your will-power into a vice and then pulls it ala Stretch-Armstrong. What happens when it eventually breaks? Rachel advises:

“It is most important that you don’t pick your baby up or feed him. This is the start of the process of teaching him that he is not coming out of his crib and he needs to go to sleep” (p67).

And then, before you can say, “is there an echo in here”, Rachel regurgitates her previous anti-cosleeping rhetoric:

“At night it is important that baby sleeps in his own room, as it is impossible to sleep train him if his crib is beside your bed. If you only have one bedroom you might consider moving out yourself, perhaps sleeping on a mattress in another room until baby is sleeping better. As during the day, turn the baby monitor down” (p65).

Sure, I’d like to see Rachel sleep on a piss-soaked mattress on the kitchen floor rather than snuggled up to her baby in a warm, comfortable bed. Go figure.

Lesson 11: Cry it out – cold turkey

Babies need us; they cannot survive without us; indeed they do not even realise they are a separate entity to us until they are at least three months old. I guess it’s hard to ignore their burdensome cries when you’re in the same room. Co-sleeping isn’t conductive to Controlled Crying, and it most certainly does not support Rachel’s next suggestion – “Shout it out”. This method of sleep training, which she also calls “Cold Turkey”, simply involves:

“leaving him to cry until he falls asleep” (p68).

“This method is tougher but works more quickly than controlled crying. You should find that your baby starts sleeping through nights after just a few” (p68).

No shit Sherlock. The baby has no choice. Ceasing to cry is not a sign that he isn’t distressed. In fact, it is likely that the baby is still distressed. Studies show that babies undergoing sleep-training still experiences a surge in the stress hormone cortisol, even when they don’t cry. So why don’t they cry? Because they have been ‘trained’ that no one will come. To use the Pavlovian phrase, it is Operant Conditioning at its most depressing.

Just when you’re starting to feel that maybe, just maybe, Rachel is an outdated sadistic baby-loather, she reminds you:

“Like controlled crying, the shout it out method can be upsetting for parents, but do remember that you are doing it for baby’s benefit” (p68).

Yeah sure controlled crying is for the baby’s benefit – and the Pope is a hardcore atheist.

Back in the real world, babies who are left to cry themselves to sleep seem to suffer long-lasting damage to their nervous systems. It is well-documented that sustained, uncomforted infant crying causes increased heart rate and blood pressure, reduced oxygen levels, elevated cerebral blood pressure, depleted energy reserves and oxygen, and cardiac stress. Cortisol, adrenalin and other stress hormones skyrocket, which also disrupts the immune system and digestion.

At this point, you may be wondering how sleep training enables a baby to feed through the night. After all, even if controlled crying, the parent must ignore the baby when they enter the room. So how can Mom feed if she is to ignore?

“Don’t worry about baby being hungry, as he will soon settle to having more in his daytime feeds. Some babies drop their night feed very early on – during their first few weeks” (p69).

First few weeks?! Show me a newborn that doesn’t need a night feed and I’ll show you my unicorn.

“You know he doesn’t really need it if he only takes a couple of ounces and looks at you and smiles and seems to think he’s going to have a party” (p69).

Noooo don’t smile at me baby! You’re taking the piss! And while you’re at it, don’t fall asleep during breastfeeding:

“Lots of mothers get into the habit of rocking or breastfeeding their baby until he is sound asleep, then putting him asleep into his crib. This seems such an easy way to settle baby when he is little, but it creates bad habits. It is better for everyone if baby learns to settle himself to sleep” (p70).

I ponder why there is no mention of those mothers who bottle-feed their babies to sleep – which is invariably worse (the milk pools in the mouth causing ‘baby bottle teeth’). Yet Rachel seems to solely target breastfeeding mothers. Most of the testimonials she cites are written by breastfeeding mothers, like this one from someone called Nicola…

Lesson 11: Switch to formula

“At about four and a half months Henry started to struggle with daytime naps and woke up more during the night. Rachel suggested that I should move completely to formula, as my milk would probably not be satisfying enough as I was so tired. I should also try Henry on some baby rice.

As soon as I gave Henry some solid food he started to sleep much, much better. He gobbled up his baby porridge and hasn’t looked back. Introducing formula feeds helped both Henry and me. I had more energy, he slept better, and I felt like I was getting a little bit of my life back” (p74).

Grruuuaahh!! That’s just the sound of me prising my teeth from the book’s spine.

I don’t need to explain the many ways in which this mother was sabotaged by Rachel’s toxic ‘advice’, it’s glaringly obvious. The formula, the solids. Yet alas, this apparent utopia Rachel had created did not last despite the precious formula – and likely because of it:

“At five and a half months, after a nasty bug, Henry’s sleep was really disturbed again. He was waking so often and crying a lot during the night. I felt as though nothing I was doing was really helping him. Rachel very calmly and gently talked me through how to start controlled crying, which gave me the confidence that this was the right thing to do. She explained that I shouldn’t leave things much longer as it is harder to do with a child who can haul himself over the crib.

The first evening of controlled crying it took Henry over an hour to settle. However – and crucially – I felt I was doing something positive to help him” (p75).

Henry, did eventually sleep through, after having his will broken by controlled crying. Nicola gleefully informs us that she can now take Henry to visit friends and family, safe in the knowledge that he won’t embarrass her with his bothersome crying. Le sigh.

If you can bear to read on, we will now look at the next chapter: Six to Twelve Months, where Rachel is quick to inform us:

“It is not too late to start training your baby” (p76).

Oh goodie.

“Chronically tired babies never settle to sleep for long and they are often grumpy or fretful. If you are at this stage, remember that sleep training is kind, not cruel, however hard you find it to listen to your baby cry” (p76).

“The important thing is to not rush in and pick him up as soon as he starts to cry” (p77).

Okay, okay same old same old. We’ve heard this all before in the previous chapters, but get this:

“Baby should not sleep in your bed. If he sleeps with you all the time he is very likely to develop an attachment problem and find it distressing to be on his own” (p78).

No empirical evidence is given for this lofty assertion. Heck, even anecdotal evidence is omitted. There’s only so much bullshit you can bolster with fictional testimonials after all.

Here, as before, Rachel advocates her gruelling ‘shout it out’ method, but concedes that there may be a few minor inconveniences with an older baby:

“An older baby may stand up in his cot and he may be sick” (p90).

That’s right. Your child may become so distressed at having been abandoned alone with no one answering his fretful cries that he gets to the point where he vomits. So what should mom do at this point?

“If he has been sick, pick him up, change his clothes and bedding without too much fuss, and settle him down again. Then leave the room” (p90).

But what if baby is hungry? Rachel admits that hunger may impede your baby’s sleep:

“If he has always been good at settling but has just started being unsettled, it is important to make sure that baby is not hungry. If you have been breastfeeding, perhaps you no longer have enough milk” (p90).

Oh fuck a duck. This is a new low. Most women give up breastfeeding because they wrongfully fear that they have insufficient milk. Before you can even say “Oh no she di’nt!” Rachel shares another testimonial from a mom called Nanette, who was unfortunate enough to take Rachel’s advice:

“I have two children: Adam is three and Alyssa is eight months old. I started to sleep in a spare bad [sic] in Alyssa’s room when she was six months old so I could get to her quickly before she woke up my son and my husband. We had tried getting him to go into [sic] Alyssa in the night, but she would scream louder and louder until I went in and fed her. We were all desperate for sleep. So I would put her to the breast and get her back to sleep.

Rachel suggested that my husband should go in to Alyssa while we do controlled crying, as she would want to feed when she saw me. Yet we were constantly arguing, we both depressed and resentful.

After another awful row I said to my mom, ‘I can’t do this anymore. That’s it, no more night feeding. I’ve had enough’. I wasn’t even enjoying breastfeeding anymore. I was finally determined to do controller crying properly. The first few nights were hard, but after that Alyssa settled herself back to sleep very quickly when she woke in the night.

With hindsight I realize that what was really waking Alyssa was me going in to her so quickly the minute she stirred. My advice to anyone now would be to wait before you go in when your baby starts crying” (p96).

All in all, this book paints an asymmetrical picture of breastfeeding and formula-feeding, with breastfeeding given the shitty piece of the cake whilst formula gets the gold star treatment. There are virtually no endearing words said about the breast, and pages upon pages of propaganda exhorting the virtues of formula.

Lesson 12: leave your toddler to cry for 2 hours

The next chapter: Twelve to Twenty-Four Months, echoes the same credence to the bottle seen throughout the previous chapters, with an extra helping of child neglect:

“At this age, you can leave your toddler to shout for forty-five minutes to an hour, sometimes longer. He will eventually go to sleep” (p115-116).

“Toddlers can shout for up to two hours when you first start sleep training” (p116).

Horrid. But remember folks, apparently:

“By teaching your toddler to sleep you are showing him more love than if you always let him have his own way, which may mean he becomes continually tired and grumpy” (p113-114).

And leaving him to cry alone for 2 hours isn’t going to make him grumpy? Logic fail.

So what on fresh earth is going on with the world’s writers? Why are a depressing amount transpiring to be pro-bottle, anti-breast proselytizers? One part of the answer is simply that for many decades most people in the developed world – including so-called health ‘professionals’ – have been more familiar with formula feeding than they are with breastfeeding. The behaviour of formula fed babies (regular feeds with long periods of sleep), together with their average intake of milk (which can be measured exactly), have been used as benchmarks for judging whether or not a baby is getting enough.

Will society ever form realistic expectations of babies’ feeding and sleeping habits? Not with literary-rags like these populating bookshelves.