Parents, particularly mothers, are a fretful sort; and book publishers are all too happy to churn out a multitude of advice books designed to direct and guide us through the minefield of parenting. Perhaps such information is welcome considering that hospitals now turf out new mothers after forty eight or even twenty four hours. Yet all such books are not created equal. Many have an agenda – sometimes hidden, sometimes explicit. During my hobby as a bookworm, I have encountered many parenting books; most have been pro-breastfeeding at best, indifferent at worst. However I have discovered a few rotten apples worthy of exposure, if only to warn mothers-to-be of their existence – lest you unwrap one of these at your baby shower. Note that I have purposely omitted Gina Ford from this list, as so much has already been written about her unsavoury breastfeeding views.

How Not to F*** Them Up. Oliver James.

We begin this list with a fairly subtle offender, so subtle that I am only going to focus on three points.

Little is said about breastfeeding in this book, which is effectively a manual about child psychology. The nutritional benefits of breastfeeding are mentioned yet the act of nursing is cloaked in heavy smog of inconvenience. The author Oliver James maintains that, “While breastfeeding you can’t take aspirin for headaches, you cannot have a glass of wine, not even one of your favourite curries or some garlic with your chicken” (p31). Such falsehoods undermine women’s confidence in breastfeeding and paint the picture of nursing one’s baby as tantamount to living in a straightjacket.

We are also told unquestionably that during breastfeeding “you are acutely aware of the need to move to a bottle so that other carers will be able to discharge this vital role as well as you” (p31), suggesting that anything else would be selfish. Not all breastfeeding mothers chose to combine bottle and breast; in fact, it would be wise not to.

Finally in a chapter titled “The Causes of Maternal Depression” James maintains that “women who breastfeed are at greater risk of depression, since they get less sleep and producing milk is tiring” (p324). In brackets after this statement James cites three studies from the eighties to act as evidence. Firstly his contention is false. In reality, the opposite is true, breastfeeding mothers get more sleep and their sleep is of higher quality; not to mention the act of nursing releases calming hormones which counteract depressive symptoms. Secondly, his use of outdated studies to bolster his view is out of sync with the rest of the book. All the other references littered throughout the book (and there are hundreds) are bang up to date. It appears that James was scraping barrels trying to find some anti-breastfeeding references and ended up resorting to vintage ones.

This book is not alone in its distaste for the (perceived) inconvenience of breastfeeding and pity for the relatives who are denied their right to wield a plastic teat, as you shall see with our next culprit which is aimed at new dads…

Fatherhood: The Truth. Marcus Berkmann.

This book is well-written, witty, insightful and genuinely hilarious; so it pains me to feature it in this list. However amongst its vast sea of astute observational humour lie sprinklings of ignorance which lower the credibility of an otherwise priceless book.

The author, Marcus Berkmann, in the spirit of most parenting guides, dedicates an entire chapter to breastfeeding which he titles simply ‘Breasts’ in bold font. That should get the target readership’s attention. In line with the overall tone of the book, some parts of this chapter elicit genuine chuckles: “Over the next few months, your partner may only ever wear clothes that allow her to whip out a tit in a second’s notice, in a way that you may have been trying to persuade her to do for some time” (p155). Furthermore his brave, albeit brief, mention of the politics involved in the breast versus bottle debate is admirable: “In past generations everyone was told to bottle-feed, as formula milk was a scientific miracle created by huge unpleasant multinational corporations unable to charge you for mammary use” (p155).

So far so good. However it is not long before some of the descriptions of breastfeeding are revealed to be careless and poorly researched. Take the following advice for example, which starts well but ends disappointing:

“Clamping baby to the mother’s breast within an hour of birth increases the chance that baby will breastfeed successfully. Some babies take to the breast immediately, and the milk gushes out, in which case, great” (p121).

This description of early feeding is clumsy and misleading. A mother’s milk does not come in until around 3-5 days after birth. Before then her breasts produce perfect teaspoon-sized portions of colostrum. Consider how the false perception that a mother should be providing ‘gushing’ milk from the get-go could damage her confidence when she finds that all she is producing is droplets of a clear liquid. She, or more relevant to this book’s target readership – her partner, may believe that her body is not functioning on par, even though in reality it is doing exactly as nature intended.

More misinformation can be observed later in the book when Berkmann informs us that: “Porn breasts may be good for masturbatory purposes but they can be bloody useless as breasts” (p157). The reality in fact, is that breasts which have undergone augmentation surgery are more likely than not to be sufficient at successfully breastfeeding a baby (La Leche League; BabyCentre; Bupa).

Throughout the book, and in particular the ‘Breasts’ chapter, such naive and erroneous assumptions are lurking in nooks and crannies, spoiling an otherwise sympathetic text:

“The fact is that bottle feeding is never going to do anyone any harm. Bottle-fed babies are not going to get fewer ‘A’ levels or fail to win Olympic gold medals (well, not because they were bottle-fed anyway). Breast may be best, but bottle is fine” (p159).

I’m reluctant to re-recycle hackneyed lactivist sentiment but I must remind readers that breast is not best, breast is normal. Unfortunately breastfeeding is the only case where the biological norm is often expressed as the exception rather than the rule. The slogan ‘breast is best’ frames formula feeding as the norm and breastfeeding as a nice extra if you’re able to do it. The reality is that breastfeeding is the normal, natural way nature intended babies to be fed. Formula is a poor substitute. However elevating breastfeeding to “best” status allows some people, and in particular formula companies, to claim that formula is “fine”. It seems that Berkmann has fallen for this charade.

The book also falls into the same old trap of many male parenting literature, namely a blokey ‘pwoar boobs’ mentality along with detachment from the breastfeeding process. Whilst recognising that bottle feeding increases the burden on the father by introducing the likelihood that he will be required to do some feeds, Berkmann maintains on the positive side, “the main advantage is that once milk production ceases the dad’s access to said breasts will no longer be denied” (p160). This assertion exploits the misconception that breastfeeding mothers are frigid martyrs and that when breastmilk is being served to baby, sex is off the menu for dad. Here Berkmann fails to appreciate the simple fact that breasts are dual-purpose organs. They are perfectly capable of being simultaneously sexual and nutritional. Amongst all the book’s stereotypical jokes of female multitasking I was surprised to find that Berkmann failed to grasp this simple concept.

Berkmann, perhaps indulging in lazy writing, also exploits another common misconception of breastfeeding – the daddy of all breastfeeding misconceptions – that ‘breastfeeding creates saggy breasts.’ Oh dear. I thought he wouldn’t go there, being an intelligent chap and experienced dad, but I was wrong. He chirps:

“Breastfeeding does change breasts. Firmness is the first casualty. A well nibbled breast will be more pendulous than it might once have been. If I had eaten a biscuit every time a mother has told me that her breasts now ‘hang down to her knees’, I would now weigh 19 stone” (p161).

The reality is that during pregnancy a woman’s breasts prepare themselves for breastfeeding, whether the mother intends to breastfeed or not. As pregnancy progresses, the glandular tissue necessary to produce milk replaces much of the fatty and supportive tissue that normally makes up most of the volume of the mother’s breast. This causes her breasts to become substantially larger and in some cases can produce the ‘pendulous’ effect that Berkmann cites. Thus the reality is that pregnancy is the culprit. Breastfeeding is blame-free.

Overall I would recommend this book for laughs, but only if you are sufficiently clued up about breastfeeding to ignore the irritating and potentially damaging misconceptions, which thankfully only infect a small proportion of the book.

When Will I sleep Through the Night? An A-Z of Babyhood. Eleanor Birne.

This book is set up in typical dictionary style from A-Z and promises to detail “all the things they never tell you”. The cover features a glowing endorsement from no other than Marcus Berkmann, author of Fatherhood: The Truth, a revelation which sets my expectations low.

Whilst oddly breastfeeding does not feature under ‘B’, various breastfeeding observations are made throughout the book. The author, Eleanor Birne, makes no effort to conceal the fact that breastfeeding made her feel “like a cow in a shed” (p111).

Nonetheless, I shan’t labour on this book for too long, as it is clear that Birne’s background story renders her breastfeeding bitterness somewhat understandable. Under ‘M’ for ‘Midwife’ Birne tells of her appalling experience at the hands of a particularly overbearing and ill-advised group of community midwives. Suffice to say demands of formula top-ups, threats of feeding tubes and hospitalisation, insensitive criticism of feeding technique, relentless weight charting and general bullying were involved. Despite my sympathy for Birne’s experience, I also believe that as an author one has a duty of care to ensure as far as possible that any advice given, particularly medical, should be as accurate as possible; The more vulnerable the target readership, the stronger the onus of care. Unfortunately such feelings of responsibility are clearly not shared by Birne. She enthusiastically mentions that she has read articles which suggest that: “The NHS is over promoting the advantages of breastfeeding” (p21). However she fails to cite her sources so we just have to take her word for it. Later she maintains that: “The claims that breastfeeding results in a higher IQ/stronger immunity/fewer allergies have been widely overstated. I quote these articles to breastfeeding mothers like some lunatic” (p22). Curiously which articles she is referring to remain a mystery.

After berating what she perceives as the inconvenience of breastfeeding, Birne’s advice begins to flow. She tells us that following her switch to formula: “Feeds now take just half an hour rather than three times as long. Both me and the baby feel liberated” (p22). Whilst Birne may feel liberated, presumably because she resents time spent feeding, it’s uncertain how the same can be said so confidently on behalf of her baby. Then again, as someone who has read every page of her book, I find it hard to absorb advice from an author who thinks it’s good parenting to take her two month old to a disco at 10pm with the music “cranked up loud” (p49), who lets her baby “fall asleep with his bedtime bottle” (p55), who lists breast shields as a hospitalbag necessity (p84), who openly boasts: “I drank my coffee holding my newborn and tried not to spill it on his head” (p82), or who thinks it is economical to leave her baby in puree-covered clothes all day (p109), a poo-stained vest (p108) or equally stained sleeping-bag (p109), whilst at the same time maintaining that her own clothes must be changed more often (p109). And BREATHE…

Needless to say I do not recommend this book to any nursing mother – past, present, or pondering. Although Birne most certainly won’t care; her view of breastfeeding mothers is made clear:

“They peer at you with your bottle and tell you they breastfed their babies until they were five years old or something ludicrous” (p21).

How to Push a Perambulator: 50 Lessons in the Lost Art of Motherhood. Allison Vale.

This book is a compilation of genuine parenting articles from the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Topics covered include ‘How to Suffer and Survive the Exquisite Torture of Childbirth’, ‘How to Manage Your Daughter’s Menstrual Flux’, and ‘How to Raise Your Daughter to Enjoy a Robust Constitution and yet Excel at Needlepoint’. All the important lessons, in other words. Due to its vintage nature we’ll cut the author some slack, however I decided to include the book in this list as it is an interesting look at how far back anti-breastfeeding propaganda originates. Indeed, some of the suggestions do not sound far removed from the advice health visitors dish out today.

The book pulls no punches in describing the tediousness of breastfeeding:

“As every mother has learned to her great cost, the handling and nursing of a newborn is an exhausting and onerous task. One may venture to state that it is indeed most unnatural [book’s emphasis] to be so closely confined to a child as to have to exclude oneself from the pleasures and comforts of society… To nurse a newborn oneself is an inconvenience beyond all consideration and as such can prevent a lady of high standing from enjoying her happiest and most influential years… Are new mothers not already weighed down by fatigue and womanly complaints which nursing a newborn would surely increase?” (p47).

The obvious remedy to such traumatic inconvenience is of course, to hand over the poor little sod to someone else for nursing:

“Giving a child over to be nursed benefits the mother greatly, as it prevents her from becoming unduly weakened by the demands of a ravenous infant” (p48).

Another remedy is to dampen the child’s appetite with other substances:

“If you resist the temptation to have a nurse suckle your infant, opting instead to offer it your own breast, cordial can bring about a dampening of its appetite, sufficient to enable you to enjoy a healthful night’s sleep without fear of disturbance” (p53).

Yet another remedy for the relentlessness of breastfeeding, and one which has endured through to contemporary times, is the use of formula:

“It is most advantageous for a mother to accustom her child early on to the benefits of artificial feeding. Not only will the demands upon the mother be less relentless and gruelling, but her child will sleep longer if fed on substances slow to digest” (p71).

Bear in mind this advice is straight from the pages of a 1770 childcare guide, and yet you can hear the words of your own health visitor tinkering in your ears as you read it. The book then continues to inform us that:

“It is also true that a child nourished in such a manner will acquire a stronger constitution, enabling it to resist, to a greater degree, the diseases and sicknesses so prevalent in infancy. A mother’s milk, although at times convenient, is often affected by the fatigue and anxiety of the mother, thereby loosing much of its beneficial qualities… A child fed on more stimulating nourishment than a mother’s own milk will surely thrive and survive ‘til adulthood” (p72).

And just in case you were still unsure of how onerous and distasteful breastfeeding is, the book reiterates that:

“A lady of high breeding knows that the distasteful practice of suckling one’s own child is to be avoided at all costs. It is ruinous to the figure, noisome to one’s dress and interferes most unreasonably with necessary quantity of gadding about. Furthermore, you will find that many husbands (of virile stock and anxious for many heirs) will not be content to suffer it: the practice renders one infertile and of little use in the marital bed for as long as one continues to indulge” (p63).

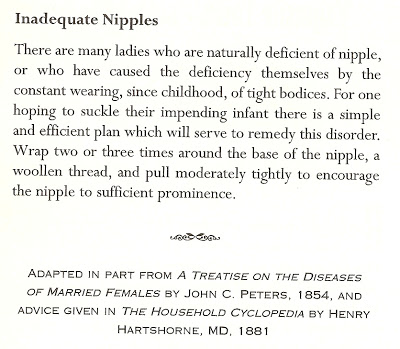

If you’re still convinced that you wish to endure the terror of breastfeeding, the book dictates that you will need to know how to deal with your ‘inadequate nipples’:

Other pearls of wisdom include treatments for medical disorders (swallowing ammonia for nausea), advice for breaking children through beating and starvation, and suggestions that too much education in girls takes away the energy needed for the menses. Needless to say this is not a book for those seeking the warm fuzzy glow of nostalgia.

The Best Friends Guide to Surviving the First Year of Motherhood. Vicki Iovine.

Back to contemporary, yet no less unsavoury, times now. This book reads like a foul-tasting recipe devised by a ranting, bitter chef. First take some brainless postnatal diet advice:

“Eat only one meal a day” (p111).

Add a pinch of pro-circumcision:

“I used to mentally compare my sons’ penises with each other’s and with my friend’s baby boys. Some looked like pigs in a blanket” (p167).

Then add a large helping of crying-it-out-propaganda:

“Repeat this mantra: Crying never killed anyone, crying never killed anyone. It certainly won’t do anything to the baby but make him tired (which is a good thing) (p27).”

Then mix in a pint of apathetic feeding advice:

“If the baby is still wailing, it might be time to feed the little thing” (p25).

Next, sprinkle on some grossly-assumptive ridiculing of co-sleepers:

“These rooming-inners are usually the same women who are marching behind the natural childbirth banner. In other words, these are women setting the rules and standards based on no actual familiarity with having a baby. Not a good idea” (p13).

And then of course, add a generous serving of breastfeeding hatred:

“Breastfeeding is as frustrating as learning to ride a bike and much more painful” (p15).

With this description of breastfeeding in mind, it is not surprising that the author, Vicki Iovine, quickly launches into dishing out dangerous breastfeeding ‘advice’. She suggests that “the first thing” you should do with your newborn is give them a dummy. She advises that with newborns “you will have to be somewhat forceful at this stage because they will not just open their mouths in joyous anticipation of the dummy” (p25). Giving a dummy, she chirps, is ideal for the ride home from the hospital after delivery: “If you have succeeded in getting the dummy into the baby’s mouth and she is sucking away like a little grouper, you may have peace and calm for the rest of the ride home” (p25). There is no warning of how early dummy-use sabotages the breastfeeding relationship. Instead she maintains that: “All my four kids had dummies while I breastfed them; otherwise I would have them gnawing on my very sore nipples twenty-four hours a day” (p25). She then continues:

“Anyway, all four gave up the dummies when they moved onto formula in a bottle. Of course, getting them to give up the bottles was no day at the beach, but hey, you won’t have to face that particular challenge for another couple of years” (p25).

I’m not going to get into the details of how unhealthy it is to give a bottle past one year, let alone for ‘another couple of years’. Needless to say, after one year babies certainly don’t need bottles. They should move onto cups. Not just from a dental viewpoint but from a speech angle too (you can read more about this issue in my article here).

Later Iovine tells us that babies, who she refers to as “feeding machines” (p137), can annoyingly interfere with a mother’s ability to regain her pre-pregnancy physique:

“Breastfeeding will NOT give you your figure back. It is a myth or some insidious La Leche League propaganda. Perhaps the theory would be accurate if you fed your baby for two years or more, since I think by that time the baby would have sucked nearly every living thing out of you, but for those of us who don’t breastfeed or intend to quit before the children are old enough to vote, it doesn’t pan out” (p113).

She continues to educate us that:

“Since the beginning of time, Nature has designed mothers to store extra fuel for those days when their men didn’t bring a boar. The extra fuel is manifested on our bodies as round cheeks (front and back), fatter upper arms and big butts. As long as you are the sole provider of nutrition for your baby, Nature is going to do her best to keep those stores in place” (p113).

The above couldn’t be further from the truth. It seems that Ms Iovine would benefit from a refresher class in the basics of biology. Weight loss occurs when we burn more calories than we consume. Breastfeeding burns around 500 extra calories per day and is thus an excellent aid to weight loss. When a woman is the sole provider of nutrition for her baby the calorific burn is at its strongest. Iovine’s ignorance and dismissal of scientific knowledge is evident again when she rants that:

“You would be amazed at how many adoptive mothers are willing to take hormones to induce their bodies to make milk. Look, as far as I’m concerned, anything that is good for your baby and good for you is wonderful, but this sounds a little bit like one of those breastfeeding evangelists got to them with the myth that better bonding(BIG buzzword) occurs when the baby actually drinks your liquids. Trust me; I know as many alienated children who are breastfed as who drank formula from a bottle” (p133).

Remember, this is an advice guide aimed at new mothers. First Iovine neglects scientific evidence regarding oxytocin and other biological mechanisms triggered by nursing (Gribble. K; Uvnäs-Moberg. K and Petersson. M; Matthiesen et al; Zetterström. R; Britton et al; Jansen et al; Else-Questet al; Furman. L andKennell. J; Uvnäs-Moberg.K and Eriksson. M), then she throws in a weak anecdote to further diminish her credibility.

In another part of the book, like a lot of seemingly anti-breastfeeding advocates, Iovine appears preoccupied with the sensitivities of men and their perceptions of breastfeeding. Perhaps this is no surprise considering her past reign as a Playboy centrefold (not mentioned in the text). She expresses her concern for men as follows:

“I have several best friends who say that their partners were turned off by the sight of them feeding the baby” (p126).

“The decision to breastfeed should be somewhat mutual. Before the baby is born, you should allow your partner to share his feelings about your suckling someone other than him” (p126)

“Unless you are a schmuck, you will listen to his concerns without threatening to report him to the La Leche League, then perhaps compromise on such things as pumping milk into bottles for him to feed the baby or promise to wean the child before she is old enough to open a jar of peanut butter unassisted” (p126).

She then provides: “A list of some of the most common considerations that help a new mother decide how she is going to feed that little thing” (p133). ‘That little thing’ presumably being the baby.

The list begins:

“1. Consider whether you feel comfortable with the notion of turning your lovely sex toys into udders for the next few months and whether your partner feels at least a little comfortable with that idea too” (p133). It is clear that Iovine has issues with human breasts, viewing them through the patriarchal lens of sex toy rather than the biological norm of infant nurturer. I would question whether someone with such a complex should be dishing out advice to new mothers about breastfeeding. Her confusion and unease with breasts acts as a thick thread woven throughout the book. Later she remarks: “Consider the newborn baby trying to latch on to a breast that is nearly twice the size of its head? It’s a good thing their sight is still fuzzy, otherwise they would run screaming from the room” (p136).

A following issue on Iovine’s list of feeding considerations is:

“Consider the condition of the mother post-delivery”. Under this heading Iovine suggests that “nearly anything ingested by the mum gets passed on to the baby through breast milk” (p135), and “breastfeeding is never an option when the mother has HIV” (p135). Both of which are false misconceptions.

The next item on the list is:

“Consider which type of food your baby tolerates better, formula or breastmilk” (p135). Is this truly a consideration worth listing? Bear in mind that formula has been found to be the cause of many allergies, whereas it is virtually impossible for a baby to be allergic to their mother’s breastmilk.

The list continues:

“Consider how serious your need for sleep is”, followed by the contention that: “All new mothers are sleep derived, but breastfeeding ones are usually particularly so” (p137). She advises that “An obvious compromise would be to feed the baby formula for one or two feeds a day” (p138). At no point does Iovine warn us that introducing formula to an exclusively breastfed baby will destroy their virgin gut and diminish the mother’s milk supply. In a book which describes itself as a ‘survival guide’, one would expect to be given unbiased information rather than information which sabotages the breastfeeding process thus removing choice from the reader.

The next item on this list of things Iovine believes new mothers should think about is: “Consider how confident you feel in your ability to breastfeed”. Bizarrely she suggests that a mother’s lack of confidence with breastfeeding will almost certainly lead to her baby’s failure to thrive: “You’ll read stories about babies who were malnourished and jaundiced because their mothers didn’t breastfeed them correctly” (p139). Surely this is a case of lack of information rather than a lack of confidence? Of course Iovine fails to mention the need for correct breastfeeding information, perhaps to obscure the fact that her book is dangerously void of such information.

The list carries on with: “Consider your threshold for pain”. Iovine tells us that “the first month can hurt so badly that you see stars and break out in a sweat whenever your baby looks at you hungrily” (p140). Just when you are ready to pass this off as a failed attempt at a joke, she elaborates:

“The single most shocking and guilt-lifting bit of truth shared by nearly all of my eight best friends was that we hoarded our prescription pain medication, no matter how badly our ‘privates’ ached, and saved them up for the critical half hour before it was time to feed. Yes, I am confessing what you think I am confessing: I took the drugs those first couple of weeks simply to endure the pain of breastfeeding” (141).

That breastfeeding is assumed to be painful is said matter-of-factly. There is no mention of the reality that when done correctly breastfeeding is pain-free. Here, Iovine prioritises sensationalist satire over factual information, which is irresponsible for a book disguised as an advice manual. She quickly dismisses proper breastfeeding technique by telling us about her “disfigured parts” and informing us that “I got just as many cracks and scabs feeding my fourth child as I did my first, and I think it would be safe to say that I had the proper technique down pretty well by then” (p141). Evidently not, as earlier in the book Iovine mentions that she has “breastfed four kids (for successively shorter times with each child)” (p136). I would hazard to guess that Iovine failed to receive adequate support to enable her to breastfeed successfully, suggested in her book’s bitter tone and lack of factual breastfeeding information. Also elsewhere in the book she holds the view that regular sickness during babyhood is normal and to be expected, which is simply not true for the majority of breastfed babies:

“In the first two years of life, little ones are often prone to colds, the flu or episodes of teething that all seem to come to a crescendo in massive ear infections” (p87).

I find it ironic that Iovine prepared a mammoth list of considerations for mothers thinking about breastfeeding, but no list for those thinking of formula feeding. This gives readers the illusion that formula feeding is easy and requires no hardship or instruction. Which again, is another gross misconception.

Finally Iovine informs us that if you breastfeed “you’ll probably eventually turn into an exhibitionist” (p142). I’d love to say that I stopped reading at this stage and promptly returned the book to the library in protest, but this is not what happened. Instead I decided to take a hit for the team and complete this exposé. The things I do for you guys…

Finally I reach the book’s climax when Iovine shares with us what she regards as “the fundamental tenet of motherhood” which she presents in block capitals: “MOTHERS DON’T HAVE TO BE PERFECT, JUST GOOD ENOUGH”. This would be a wise statement if it weren’t made purely in regard to breast versus formula. As pointed out throughout my blog, formula is often not ‘good enough’.

We are then showered with pro-formula cliché after cliché; the usual suspects are paraded, including: “As our own mothers will quickly point out, our entire generation is a testament to the fact that formula-fed babies can survive and even prosper” (p144). I would argue that as mothers we should aim for a little more than survival for our babies. Regarding prospering, I would urge Iovine to at least attempt some research on the inadequacies of formula.

‘Babies for Beginners: Keeping your baby happy and healthy’. Roni Jay.

This book disguises itself as a balanced exploration of the options available to new parents regarding such common battlegrounds as feeding, weaning, sleeping, crying and so on. In reality the book is heavily biased, sometimes blatantly, sometimes subtly, always irritatingly. For our purposes, we’ll focus on feeding.

The author, Roni Jay, splits her analysis of feeding into three chapters with the predictably bland titles of ‘Breast versus bottle’, ‘Breastfeeding’ and ‘Bottle Feeding’.

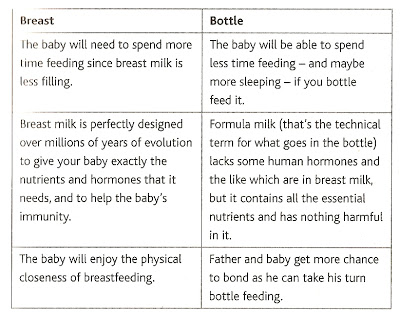

First we are greeted with this illustrative comparison of breast versus bottle:

Wow. Look how glamorous the bottle feeding Mum appears with her flowing locks and lipstick pout; and Dad’s glowing with pride and self-satisfaction – everyone’s a winner in Camp Bottle. However over at Camp Breast, it seems all a parent can content themselves with is not having to sterilise (unless she’s pumping, in which case she will have to sterilise, which according to this analysis would leave zero advantages in Camp Breast). Notice the illustration’s convenient lack of consideration for the baby’s needs. When such needs are ignored, bottle feeding looks like an obvious winner; however considering the key objective of the book (as embossed on the cover) is “keeping your baby happy and healthy” the content is nothing short of misleading hypocrisy. The true title should be “Babies for Beginners: a patronising and erroneous guide to achieving maximum parental convenience”.

Firstly the book is patronising in that on every page it will state the bleeding obvious in language so retarded and simplistic that it would form an excellent script for Cbeebies. Take the part about breastmilk expression for example; the segment is titled “EXPRESSING: WHAT’S THAT ABOUT, THEN?” and begins by explaining “You use a bizarre contraption called a breast pump (definitely not one to try in public)” (p34). This is either lazy writing or an awkward attempt at humour. Either way, you can expect much more of it. The bottle feeding chapter fares no better, with advice including, “Some tins have strange names like ‘follow-on milk’ but you want the one which says for newborns” (p51), and when explaining the process of bottle feeding, Jay advises: “Step 6: Put the squishy end of the bottle in the baby’s mouth” (p53).

Secondly, the book is erroneous in ways so blatant that you begin to wonder whether it’s intentional. In a section titled “Recognising when it’s feeding time”, the text maintains that: “Basically, if it cries and hasn’t been fed for a while, chances are it’s hungry. If it doesn’t cry, it isn’t hungry” (p52). I can only assume “it” refers to the baby and not some generic life form. There’s no mention of feeding cues (fist sucking, rooting) nor the fact that if a baby is left to cry before being fed he/she is unlikely to feed properly and more likely to develop colic.

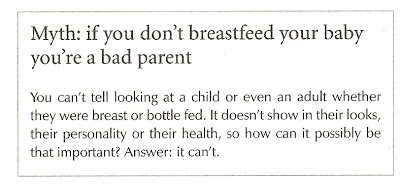

Carrying on with the flow of incorrect information, in the ‘Breast versus Bottle’ chapter, we are told that that there is no difference between breast and bottle feeding in terms of health (or looks or personality), and therefore the feeding method a mother chooses is unimportant:

I’m not going to use blog space listing the stats on infant feeding method as a determination of lifelong health (they are widely publicised in the press and scientific journals and I have written about them copious times before), suffice to say that Jay has chosen to omit them.

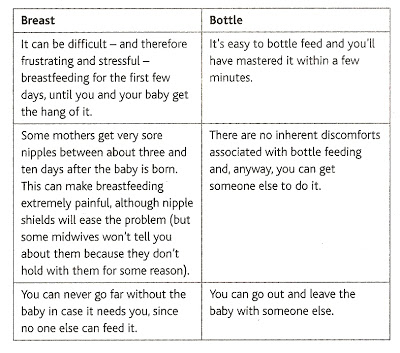

Curiously there is a lot Jay has chosen to omit from this book. When discussing the benefits of each feeding method she provides the following table (I have scanned it in its entirety):

There’s no explanation of the vast nutritional differences between breastmilk and formula; only that formula lacks “some” hormones but this doesn’t matter because it “contains all the essential nutrients and has nothing harmful in it” (in reality this is false, as many formula recalls have proven). You begin to wonder whether Jay has shares in Milupa.

Later she warns us that: “Once you stop breastfeeding your milk soon disappears and that’s that” (p33). There’s no mention of relactation; probably because that would conflict with her pro-formula agenda.

She also warns that a breastfeed is likely to take “at least an hour” (p39). Seriously, if this happens to you, I urge you to contact a reputable breastfeeding counsellor. A healthy baby with correct latch should not take this long for a single feed. I find myself wondering whether Jay has knowingly exaggerated the burdens of breastfeeding including the timing involved. This suspicion is further fuelled when after explaining how much easier it is to bottle feed on the move, we are told “It is possible to breastfeed a baby while standing up and walking around, but it does nothing for the flow of milk” (p30) – whatever that means is anyone’s guess. No explanation is given.

The virtues of bottle over breast are also touted in regard to car travel: “In a car a second adult can bottlefeed the baby while they’re both strapped into their car seats (potholes help wind the baby)” (p30). I question whether potholes are an adequate substitute for burping a baby – particularly given that bottlefed babies need burping significantly more often than breastfed ones (Journal of Behavioural Processes; Maternity and Infant). Not to mention the lack of intimacy this method encourages and the risk of choking.

This parental-convenience-over-infant-welfare attitude is a common theme throughout the book. We are informed unquestionably that, “The best way to feed your baby is whatever way the mother feels happiest with” (p31), followed by this table:

Biased some? If you were reading this as a pregnant novice you’d be forgiven for assuming that bottlefeeding is what mothers feel happiest with, and therefore (according to this author) the best way to feed a baby.

Later the book provides a list of “Breastfeeding Side Effects” which it determines are: leaking, overfilling, refilling, sore nipples and after pains. There is no mention of other breastfeeding side effects: healthy weight regulation, reduced risk of breast cancer, reduced risk of uterine and ovarian cancer, promotion of emotional health, lessening of financial burden, and so on (I’m sticking with the parent-centred approach by listing only maternal benefits; the benefits to the baby are vast).

Even the father’s pride is placed above the best interests of the baby: “The father cannot breastfeed the baby; this means that he is pretty much excluded from the intimate mother-baby relationship for the first few weeks” (p32). Although using slings to enhance paternal bonding is suggested, the book later warns us that: “If you decide to breastfeed, it is hard to emphasise with how stressful it is for the father to be left with a hungry, yelling baby which he has no way of feeding; by bottle feeding everyone gets an equal go at playing with the baby” (p50). I’m confused why breastfeeding prevents the father from playing with the baby?

It would be wise to give this book a miss if you want factual, supportive and unbiased parenting information. On the other hand, if you wish to become more confused than before, or if you have already chosen to bottlefeed and want a back-pat, jump right in.

And finally, the winner for most anti-breastfeeding parenting book goes to…

‘Bring it on Baby: How to have a Dudelike Pregnancy’. ZoeWilliams.

The title itself is a tad suspect, so should I have been surprised by the content? The book calls itself “a straight-talking corrective to the sea of advice that engulfs pregnant women and new mums”. I call it: one woman’s sea of regrets regurgitated into a sulky, bitter rant. Even the dodgy title was not enough to prepare me for the resentful, almost venomous, assessment of breastfeeding given by the author Zoe Williams. The entire book lacks purpose and is packed with unintended irony. For instance, the text tries too hard to be rebellious yet sincere; and every chapter consists of Williams taking her personal experience and passing it off as widespread fact. Not only is her description of breastfeeding overly-negative, in parts it is wholly inaccurate. Williams, a (seemingly perpetually angry) woman, maintains that “in its aftermath, breastfeeding makes your tits look like bananas in a Waitrose bag, and while you’re doing it, it interferes with sex” (p93). Perhaps Williams does not realise that it is wise to unlatch the baby before having sex?

Her naivety, or should that be exaggeration, continues into the realm of breastfeeding in public: “I ripped all my clothes off as if in a strip joint frequented by early man” (p85). Later on she rants: “If anyone can come up with a way to get a picture of a breastfeeding baby without getting a great big breast in the way, then I will find a way to give that person a Nobel Prize” (p86). Presumably Williams not only misunderstands the concept of discretion but also thinks that a picture of a breast is abhorrent.

As for her advice on whether to choose breast or formula, Williams contends that: “Formula looks nicer; it would surprise me in no way if it didn’t also taste nicer” (p89).

With regard to babies sleeping habits she retorts: “H wasn’t sleeping well, which I put down to the fact that breast milk only fills you up for about 36 minutes, indeed, from a satiation perspective is useless, is essentially water that tastes of booze and garlic” (p88).

The book is littered with such advice; however would you seek counsel from an author who spends a whole chapter throwing a tantrum about being advised not to drink in pregnancy? Not to mention that her advice is driven by assumption and lacking any kind of evidence, scientific, statistical or otherwise. She contends that:

“The case for breastfeeding is not that strong, and it has passed so seamlessly into the book of What’s Best for Baby that it’s often very lazily put” (p90).

Conveniently Williams fails to mention that decades of scientific research and millennia of evolution verify breastmilk’s enduring superiority.

Sadly, this selection of books is merely the tip of the literary anti-breastfeeding iceberg.

Jump to: PART TWO (If you dare)

Spread the word – pin it!