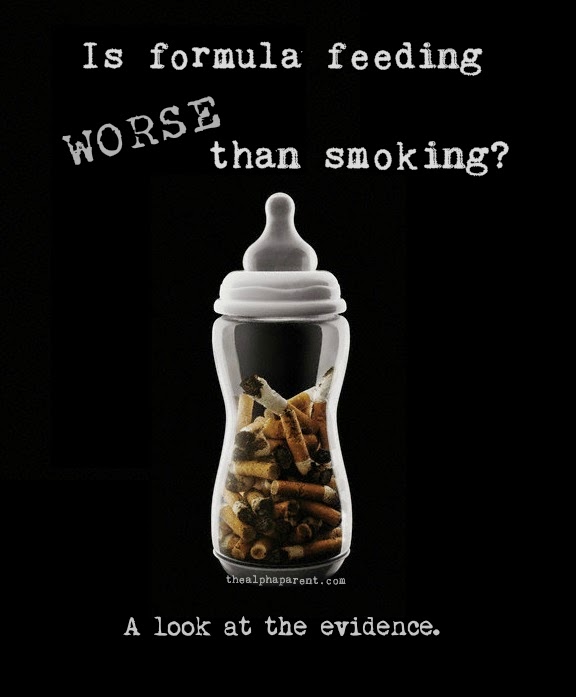

When you read the title you probably thought, ‘But formula is nothing like smoking, jeeeeez!’ On the contrary, there are numerous parallels. In this post I’m going to set out, not only why formula feeding is like smoking, but why it may even be considered worse.

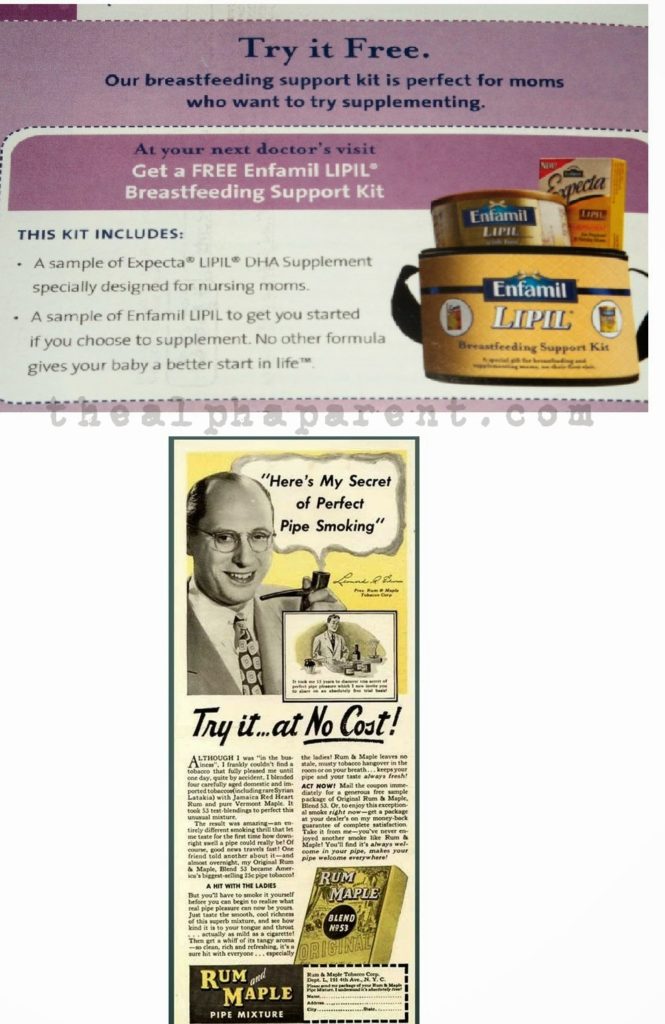

Firstly, a common thread between formula feeding and smoking is consumption patterns. They both follow the addiction model: It’s easy to get hooked, and then you’ve gotta have it (see what I mean, here). During World War II, soldiers were issued with free cigarettes, courtesy of the tobacco companies, whereas today formula companies gatecrash maternity wards, doctors’ surgeries, and parenting magazines proselytizing with free formula:

Health cover-up

Mark my word friends, in the not so distant future, lawsuits will be filed against formula companies claiming that they are responsible for the ill-health of the obese, diabetics, crohn’s sufferers, allergy sufferers, arthritis sufferers and asthmatics, to name but a few of the possible plaintiffs, who fed for a considerable period of their infancy on their products. No, this isn’t some kind of joke. I liken such a legal challenge to the fight against ‘big tobacco’ in the nineties. People ridiculed those attempts too, but in 1998, the Master Settlement Agreement saw the major US tobacco companies agree to pay $246 billion over twenty-five years to settle lawsuits filed by US states.

From a legal point of view, there are certainly precedents set by the tobacco suits which those pursuing formula companies can utilise. One legitimate way we can draw an analogy is to identify a common logical structure. For example, it can be maintained that the arguments against the tobacco and formula industries have the same form, namely:

1. If a manufacturer covers up the harm its products can cause, it is responsible for any such harm its products do cause.

2. X has covered up the harm its products cause.

3. Therefore X is responsible for any such harm its products have caused.

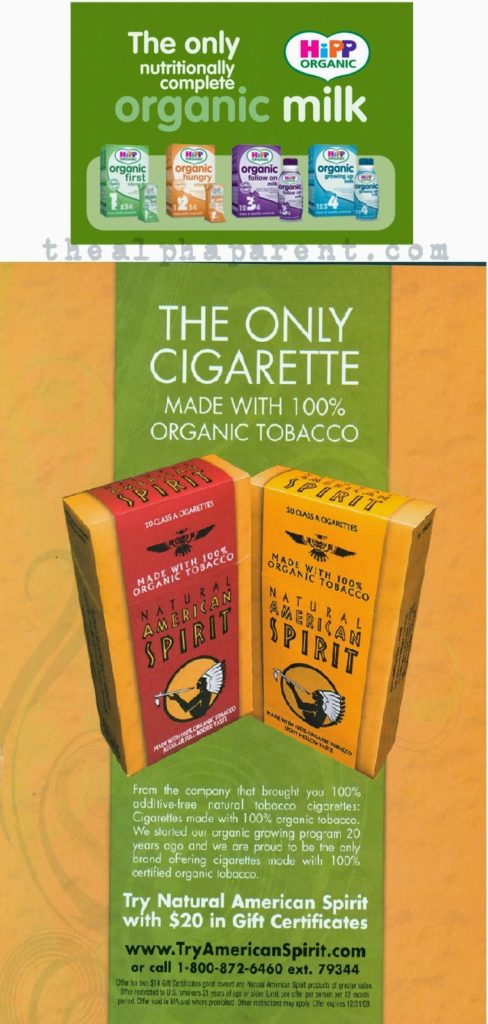

Organic ill-health HAS to be better than regular ill-health, right?

Bogus compari.

“30 years research” makes it all right, allegedly.

“Protection”. Nuff said.

However, the fact that arguments against big tobacco and the formula industry have the same structure is not in itself very interesting. What’s really important is whether the content of the arguments is analogous, not just the forms. Has the formula industry engaged in a health cover-up comparable to that of the tobacco industry? I would argue that they have. In the UK for example, according to a survey undertaken by the UK government, 34% of mothers incorrectly believe that infant formula is the same or almost the same as breastfeeding. Another survey conducted by Unicef found more than a third of mothers thought formula was ‘as good’ or ‘better than’ breastmilk. Let me present one more fact for you stats fans: a massive 9 out of 10 mothers questioned in a British Heart Foundation (BHF) survey misunderstood marketing information when feeding their child. The study found that mothers believe claims such as “a source of calcium, iron and six vitamins” mean a product is likely to be healthy.

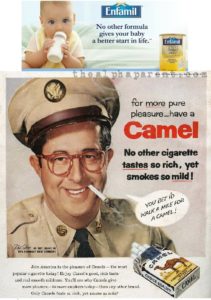

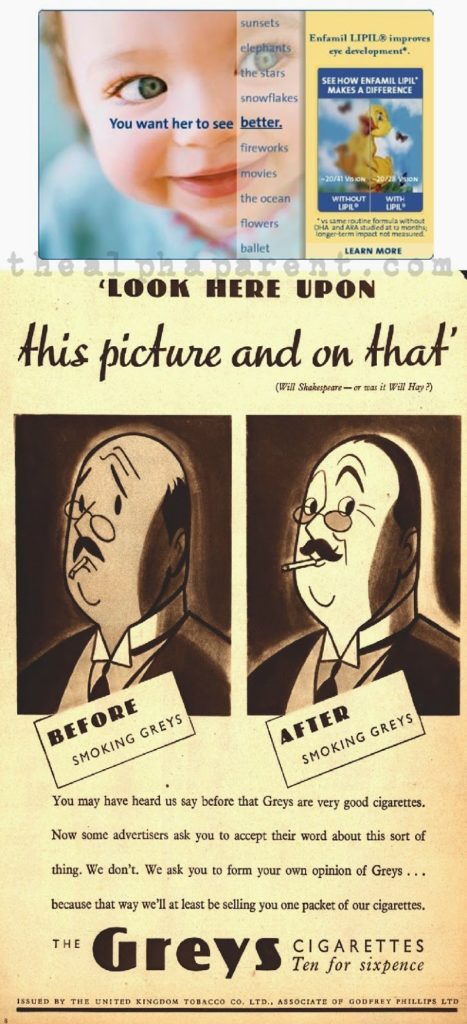

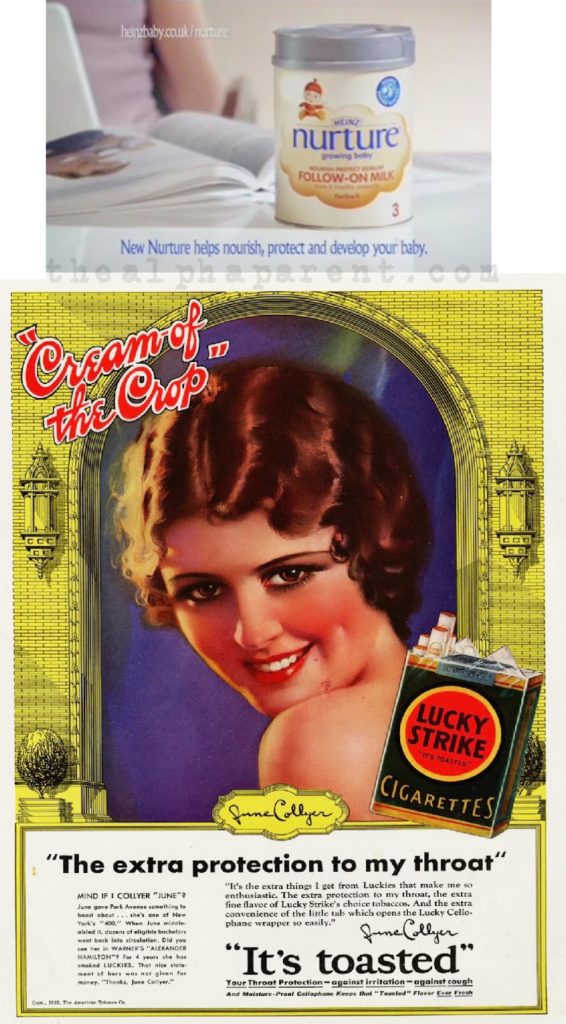

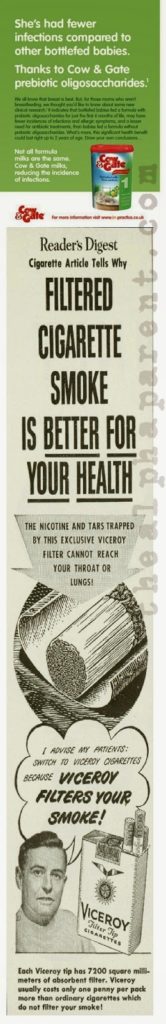

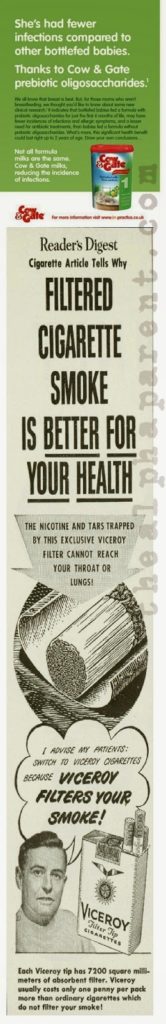

By asserting that their products are safe for babies, and even, advantageous, formula companies have orchestrated a cover-up on a monumental scale. The analogy with the past antics of the tobacco industry is glaring. As the Drug Policy Foundation maintains, “Tobacco products have had a long and inglorious history of largely unfettered marketing built around pseudoscience, false and misleading claims, and appeals to medical authority.” Sound familiar? This is the current under-regulated marketing arena that formula companies enjoy today. Take these two ads for example:

Notice at the bottom of the cigarette advertisement, it features a doctor with a speech bubble containing his advice on cigarettes: “I advise my patients to switch to Viceroy cigarettes, because Viceroy filters your smoke!” The ad claims that filtered cigarettes, especially those with Viceroy filters, are “better for your health” than cigarettes without filters. In a similar vein, the formula ad claims that babies fed that brand of formula have fewer infections than babies given other formulas. The underlying message behind both ads is the same: our product causes health problems, but not as many health problems as our competitors. The consumer focuses on the latter part of that sentence when what they really ought to be focusing on is the initial confession.

As I have explained in depth elsewhere, just as loaded words try to manipulate parents emotionally, pseudo-scientific jargon tries to induce an unearned respect for what is said. To bolster their claims, the ads above use ‘authorities’: the formula company quotes ‘research’, the tobacco ad quotes a ‘physician’.

There’s one physician however, who isn’t taken in by such strategies. Jack Newman MD works with thousands of mothers and babies every year in his clinic at the International Breastfeeding Center, Toronto. He’s argued that all pregnant women and their families need to know the risks of formula feeding:

“If mothers get the information about the risks of formula feeding and decide to formula feed, they will have made an informed decision. This information must not come from the formula companies themselves, as it often does. Their pamphlets give some advantages of breastfeeding and then go on to imply that their formula is almost, actually just as good.”

Patti Rundall, policy director at charity Baby Milk Action agrees. She contends that mothers “should know the risks of formula feeding, which include higher incidence of ear infections, arthritis and many other conditions. Often just pointing out these risks is seen as aggressive promotion of breastfeeding, but people should know the dangers. And we should not have the sort of promotion of bottle- feeding in the UK, which encourages mothers to think it is the norm and carries no risks.”

Another leading charity, aptly named: Save the Children, is also in agreement and has recommendedthat formula should have tobacco-style health warnings informing parents of the risks associated with formula feeding, not in wimpy small-print. They want the messages to be big enough to cover at least a third of the packaging. Reckon they’ll succeed? Not without a bitch-fight. Any attempt to quash the free-reign free-market predatory behaviour of formula companies is sure to be met with staunch defiance. Economic power is a force only the brave dare challenge. For instance, in 2007, when the Philippines tried to limit formula advertising, several formula companies took the issue to court. The court sadly ruled against a ban on baby formula advertisements. However, on the plus side, the court stood firm on restricting potentially misleading health claims and also increased regulation of such ads. Not unlike the FDA Tobacco Regulation Bill, which compelled tobacco companies to eliminate potentially misleading labels like “light” and “mild,” regulate a product’s ingredients and increase the size of the warning labels on cigarette packs. One blogger pondered: “The high court decision about the tobacco advertising got me thinking, in fifty years time, will the idea that formula was marketed as a health product seem unbelievable? I hope so.”

I hope so too. Like smoking, the risk of using formula cannot be negated. Even properly-prepared formula carries numerous health risks. Warnings such as those now placed in advertisements by the alcohol industry – ‘use our product responsibly’ – would not be out of place on formula cans. At present, the best we have is teeny tiny small-print the size of two postage stamps tucked into the ingredients list:

Defensive Users

Recall previously, I wrote about formula feeders and denialism. It’s interesting to note the parallels in rhetoric used by the defenders of formula and the defenders of tobacco. It should be obvious that no facts about the risks of either can ever be proved beyond all doubt whatsoever. What some defenders latch onto however, is that despite the facts of formula and tobacco’s risks having overwhelming evidence, they do not have quite as much as most well-established scientific truths (the existence gravity for instance). So, although there is very strong evidence that smoking is a major cause of lung cancer, there is wiggle-room available for defenders to demand a higher standard of proof and claim science has not met it. As illustration, take a look at this quote direct from Imperial Tobacco legal documents:

“Cigarette smoking has not been scientifically established as a cause of lung cancer. The cause or causes of lung cancer are unknown” (The Observer 2003).

Yup, they actually said that. Does this rhetoric sound familiar? That’s because it’s the same strategy formula defenders use when referring to the risks of formula:

“Formula feeding has not been scientifically established as a cause of SIDS. The cause or causes of SIDS are unknown”.

Science is by its nature fallible and to demand infallibility from it is to disobey Aristotle’s wise injunction to expect only as much precision as the subject matter allows. Like the connoisseur of good vodka, the truth seeker should not demand 100 per cent proof. We have to live with a small measure of uncertainty.

Many formula feeders have the same illogical understanding of the health issues with formula feeding as they did of smoking in the 1940’s: “If I can’t SEE how this lifestyle choice makes a difference to health then there can’t BE a difference.” Yet if the impact of lifestyle choices on health was so obvious, women wouldn’t have been positively encouraged to smoke and eat liver in pregnancy for decades. Can you look at a group of adults and tell whose mother smoked when they were in utero? Not all damage is visible to the naked eye, my friends.

Failed duty of care

Like smoking, formula feeding is a personal decision and an expression of one’s freedom. Yet the consequences of that decision and their impact reflect an important dichotomy. Here, we are getting to the crux of the ethical implications: unlike the smoker, the end-user of formula is not the decision-maker. Whilst a smoker can chose to endanger their health, a baby has no choice. This victimisation, this betrayal, is what makes formula feeding trump smoking in unethical terms. Infants are a vulnerable group. They rely on their caregivers to protect their best interests. Like the parent who fails to protect their child from second-hand smoke, the mother who abandons breastfeeding without a fight has failed in her duty of care. Given that formula feeding is involuntary on the child’s part, and given that the health risks are well documented, it is not a stretch to argue that formula feeders are playing the same ethical ball game as smokers. With regards to smoking, the majority of passive smoking occurs in the home and children are the prime victim, and whaddya’ know, with regards to formula feeding, children are the prime victims. Yet surely in an ethical society, child health should be prioritised over adult convenience?

Consider also that the staggering healthcare costs of treating diseases caused by both smoking and formula feeding. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention smokers costs $96 billion a year healthcare costs and $97 billion a year in lost productivity. Likewise If 90% of US families could comply with medical recommendations to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months, the United States would save $13 billion per year (Pediatrics 2010). Like smoking, formula feeding puts an unfair economic burden on non-users, a legitimate public health concern.In closing, there needs to be public debate focusing on issues such as the regulation of formula marketing and the disincentivization of formula feeding (Both of which I have discussed here). The ethical issue, I believe is one of freedom versus responsibility. Where does a mother’s right to exercise a lifestyle choice end and where does her responsibility to her infant and to society begin? Mull that one over for me.

Dare you pin it?

References

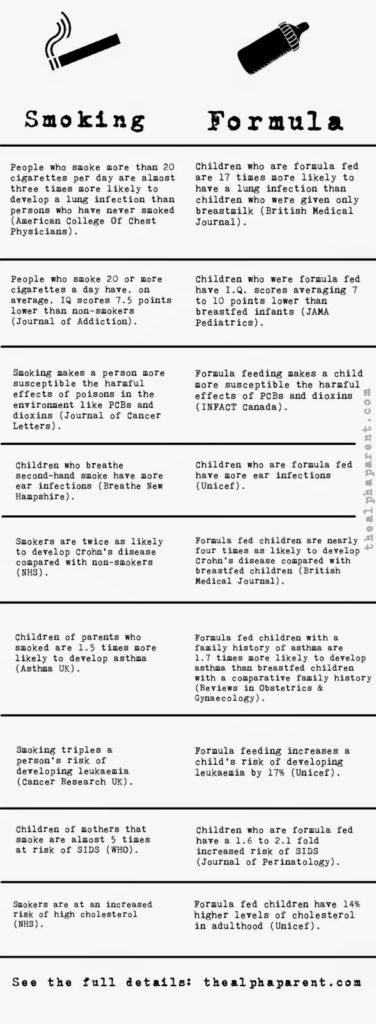

Lung infection:

American College Of Chest Physicians.

British Medical Journal.

I.Q:

Journal of Addiction.

JAMA Pediatrics.

Environmental poisons:

Journal of Cancer Letters.

INFACT Canada.

Ear infections:

Breathe New Hampshire.

Unicef.

Crohn’s disease:

NHS.

British Medical Journal.

Asthma:

Asthma UK.

Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynaecology.

Leukaemia:

Cancer Research UK.

Unicef.

SIDS:

WHO.

Journal of Perinatology.

High cholesterol:

NHS.

Unicef.