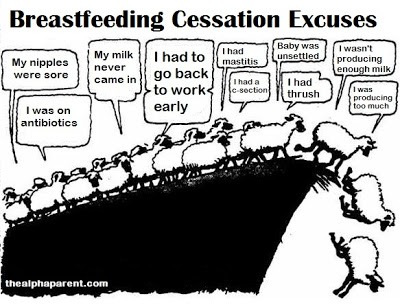

I’ve had experience of numerous people moaning that they’re having to quit breastfeeding for the usual reasons: they don’t think they’re making enough milk, baby isn’t gaining weight fast enough, they’ve got mastitis, etc. However when I offer the relevant advice, direct them to local breastfeeding support groups, recommend books – they ignore it.

This leads me to the logical conclusion that they already made up their mind to stop breastfeeding because they can’t be bothered. And the reasons they give are mere excuses used to mask their laziness. Think I’m being harsh? Read on.

Self-Sabotage

Before breastfeeding cessation, these mothers are prone to aggravate their feeding difficulties. Strange as it may sound, they often fail by choice. A lot of them dislike breastfeeding and thus actively seek a get-out clause, latching onto a difficulty and consciously rejecting solutions.

Such mothers fail to accomplish tasks crucial to their breastfeeding success (demand feeding for example). They set themselves up to fail, associating with people and situations that are sabotaging to their breastfeeding relationship (for instance, they are fans of the permissive midwife which says, “it’s okay to give a bottle if it’s best for you” rather than staying clear of such people).

When every effort is made to help them, or to present a solution to their breastfeeding issues, such efforts are met by a huge arsenal of reasons why it will not work, or simply ignored. They want to give up breastfeeding, but they don’t want to admit responsibility for this decision.

Breastfeeding is hard work

Such quitters moan about ‘having’ to stop because they feel guilty and they want to give other people the impression that they are stopping reluctantly. By moaning, they feign a sense of helplessness.

Don’t get me wrong, formula feeding isn’t a walk in the park, but arguably breastfeeding is more intensive. Our society does not easily accommodate breastfeeding mothers. The numerous societal breastfeeding boobie traps erect unnecessary hurdles in the path of the breastfeeding mother – clueless family members, returning to work early, the misguided controversy of public nursing, poorly trained health professionals, stigmatisation of cosleeping, frumpy nursing bras, insidious formula company marketing, Clare Byam-Cook.

Add to these societal hurdles the natural hurdles that are part of breastfeeding – the relentlessness of cluster feeding, the uncomfortable uber-engorgement, the leaking, the older children buying for your time, and so on. There can be no procrastination where breastfeeding is concerned. No laziness. You can’t pass the buck. Nursing has to be done, over and over again, multiple times a day.

It is not morally acceptable to excuse ourselves from responsibility and obligation solely because circumstances arise which we do not have complete control over (mastitis, tongue tie, illness for example). We parents have two choices when circumstances catch us by the neck. We embrace them and work through them or we declare ourselves the victim and excuse ourselves. Successful breastfeeders do something to address their problems, and get on with it. They research, seek (and take) advice, and have a level of commitment strong enough to embrace delayed gratification.

The intensity and totality of the breastfeeding relationship is extremely profound—it requires a more complete physical/body investment with someone than you will ever have with anyone else in your life, including sexual relationships. A lot of women, however, are turned off by this level of commitment.

A matter of priorities

As mothers we have to prioritise conflicting demands – for the bulk of mothers who trade breast for formula, breastfeeding wasn’t top of your priority list. Just be honest about it. Other things were more important to you than your breastfeeding relationship. These other things may be: older children; undisrupted sleep; being employed without having to pump in an office lav; wanting to measure your baby’s consumption; your ability to go out on the town; and ‘having your body back’. Unsurprisingly, research has shown that the strength of the intention to breastfeed is an accurate prediction of breastfeeding success (Blyth et al; Forster et al; Ryser), perhaps even the most important factor (DiGirolamo et al; Swanson & Power). “Most women who choose to breastfeed can succeed if they give breastfeeding a fair trial” (Dr Benjamin Spock 2004).

Instead of admitting that breastfeeding was too much hard work and didn’t fit in with their lifestyle, family makeup and preconceptions of mothering – most quitters reel off a list of ‘excuses’. By broadcasting to people that they at least endeavoured to breastfeed, they aim to avoid the stigmatised status attached to mothers who aimed to formula feed from the start.

The Blame Game

Although their own actions (or lack of) are almost always responsible for their breastfeeding failure, they are very talented at finding excuses why things don’t work out. They take refuge in victimhood and blame others for their breastfeeding failure.

Blaming others can have a cathartic effect. We should never underestimate the sense of relief that comes with shifting the responsibility for our failings onto someone or something else. This is particularly so when parenting is concerned. Parents (rightly) carry the bulk of the responsibility for their child’s welfare. When they mess this up, they (rightly) feel guilt. Offsetting this guilt onto others brings great relief.

It’s a form of denial. Excuses mask a weak-resolve and shift the blame to the allegedly ‘truly guilty party’. The baby for their lack of cooperation, the midwife for her lack of time, the husband for his lack of support – all are common scapegoats, but the most popular appears to be anatomy. By falsely blaming their body’s lack of cooperation they relinquish responsibility, shifting the blame away from themselves and placing it on their fictional ‘broken boobs’. This, in turn, obscures the fact that effort can overcome most breastfeeding issues. Baby not gaining fast enough? – have you seen a paediatrician to rule out other issues? Returning to work early? – have you looked into your expressing rights? Got mastitis? – take some paracetamol to stabilise your temperature and nurse frequently. Sore nipples? – I’ve got a cream for that. But often, you’re not interested in my advice or solutions. You’ve made your mind up. You’ve thrown the towel in. That’s okay, it’s your choice to make. Just be honest about it.

The formula feeder believers herself to be a victim of circumstance. She is a victim of others’ decisions. “I didn’t decide this. I can’t control it. Why should I have to take the blame for it?” underlines her thought processes. Studies have shown that these failed breastfeeders often cite fictitious reasons for their failure (Bailey et al 2004). Yet I have more respect for mothers who are honest and say “I’ve given up breastfeeding because I can’t be bothered with it anymore” than mothers who reel off a list of excuses to anyone who will listen.

And who is listening? Often it’s other mothers and mothers-to-be. If they are formula feeding mothers they will nod knowingly. They know the game. If they are breastfeeding mothers, they will nod with feigned sympathy. For if a breastfeeding mother were to offer advice or woe betide, question the decision, they will be seen as a ‘breastfeeding nazi’.

Excuses and their consequences

What is most concerning is that the list of excuses can sound plausible to the untrained ear, and their believability obscures reality. Your breasts aren’t producing enough milk? Well you know your breasts better than me I guess. Let’s forget about the scientific truth that the vast majority of breasts produce sufficient milk (otherwise as a species we’d all be extinct). You’ve got mastitis – that’s painful! Let’s forget that it can be treated and one of the best treatments is continued nursing. Your baby is not gaining weight fast enough? How horrible. Let’s forget that this could be down to human error in interpreting charts or an unrelated medical issue.

Using excuses not only shifts the audience’s attention away from the excuse-maker’s lack of perseverance, it also insults the intelligence of the listener. “One mom defends her right to bottle-feed her baby without judgment. We’re with her. But then she tests our theoretical tolerance by giving her reasons” commented feminist magazine Jezebel in an article titled, “Not Breastfeeding Is Fine, But What About Her Reasoning?”

Perhaps more importantly, by using excuses, these mothers are exacerbating society’s fear of breastfeeding. The more often excuses are used – the more new mothers will see breastfeeding as biologically ‘unrealistic’. When excuses are used, attention is drawn away from the pertinent issue of effort. For instance, the most common excuse I hear is “my breasts aren’t producing enough milk”. The reality is that your breasts are almost certainly producing enough milk but your confidence in your body has been undermined by ignorant yet well-meaning family members, poorly-trained health professionals, and clever formula marketing. If you had read that book I recommended, you would know this. But that would take time. It would take effort. It would mean having the balls to rebel against the family members, the health professionals and the formula companies

Another common excuse is that the mother had a caesarean delivery. However there is no reason why a caesarean should prevent breastfeeding. In fact, once breastfeeding has been established birth experiences do not have a lasting effect on breastfeeding duration (Cernadas et al; Dennis; Scott et al). By placing the blame on their caesarean, such mothers are setting an expectation of failure for future c-section mums. The inverse correlation between caesarean rates and breastfeeding rates has less to do with the method of delivery and more to do with peoples false preconceptions of c-sections as a barrier to breastfeeding.

The omnipresent abundance of excuses leads to what I call a ‘sheep mentality’ or to put it another way, a culture of ‘failure acceptance’. Numerous studies have shown that “low expectancies of success are a liability in performing difficult tasks” (Brown. J et al). So with regard to breastfeeding, would-be mothers hear the excuses and consequently they view successful breastfeeding as near impossible. When they get pregnant they use the discourse of ‘try’ – they say they will ‘try’ to breastfeed, they’ll ‘give it a go’; they anticipate failure before they’ve even started breastfeeding because that’s all they’ve heard from other women (Bailey et al 2004). Would-be mothers form a false preconception that breastfeeding is, for the most part, a matter of luck; that women’s bodies regularly malfunction. When their baby is born some mothers avoid breastfeeding altogether, so as to avoid failure (Martain. A and Marsh. H). For those who start, most of them encounter a breastfeeding issue and give up because failure is imminent – it must be, all their friends failed. It looks like their body too, has malfunctioned.

“In a sense, she is looking for signs of failure. If her baby cries one day a bit more than usual, her first thought may be that her milk has decreased; If the baby develops indigestion or colic or a rash, she is quick to suspect her milk” (Spock 2004).

In one study, O’Campo et al found that maternal confidence was the most significant of 11 psychosocial and demographic factors effecting breastfeeding duration. Women with low breastfeeding confidence were three times for likely to give up breastfeeding compared to very confident breastfeeding women. Similarly, Buxton et al found that 27% of women with low confidence in the prenatal period discontinue breastfeeding within the first postnatal week compared with only 5% of the highly confident women. Propagandising excuses lowers the confidence of would-be breastfeeders everywhere, and therefore has consequences that reach far beyond the excuse-maker.

Scapegoating Vs Genuine Excuses

How can you tell an excuse-maker from a mother who genuinely couldn’t breastfeed? This is a tough question, as both use anatomy in their dialogue. One way of differentiating between them is by the level of defensiveness. The excuse-maker is likely to get offended by health campaigns pointing out the dangers of formula, and by adverts such as this. They make comments such as, “this makes mothers who can’t breastfeed feel bad” and “this makes us feel guilty”. Mothers who genuinely couldn’t breastfeed however, know that they truly couldn’t and have a valid reason, so are less racked with guilt. There was a lack of free will. They know deep down, there was nothing they could have done to salvage the situation. These mothers are harmed by the excuse-makers.

Indeed, if you’re a formula feeder reading this and you’re angry because you had a genuine medical reason for your inability to breastfeed (insufficient glandular tissue, mastectomy, incompatible medication for example), perhaps redirect some of your anger onto the women that had the functioning breasts yet lacked the effort. It is these women that fuel the ‘formula feeder as lazy’ stereotype. Salvaging their own reputation is more important to them than the welfare of other mothers and babies, and indeed, their own baby.

One of the common complaints of these mothers is that they did not receive enough support to enable them to breastfeed. However all the support in the world is not going to resolve your breastfeeding problems without the requisite effort, compromise and sacrifice on your part. Sometimes it takes a hell of a lot of effort, and the mother decides it is too much. In this instance, please stop using excuses. Just admit that breastfeeding success, rather than being a biological certainty, is for the most part, a result of good ol’ fashioned effort.

Only when we lift the veil on excuses can we as a society focus our resources appropriately, and make breastfeeding easier.