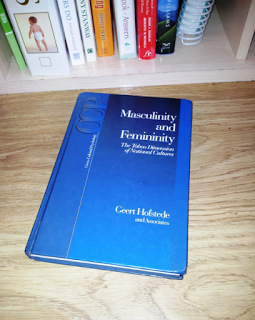

Whilst indulging my inner bookworm at the local city library, I unwittingly stumbled upon a book written by a man called Geert Hofstede. Hofstede is an influential Dutch researcher well-known (in the social-psychology clique at least) for his research of cross-cultural groups and organizations. He played a major role in developing a framework for assessing and differentiating national cultures. Reading his jaw-dropping, hugely under-utilised trove of research has radically deepened my understanding of why we suck at breastfeeding in our society. It triggered an epiphany of sorts. And his book wasn’t even about breastfeeding!

Whilst indulging my inner bookworm at the local city library, I unwittingly stumbled upon a book written by a man called Geert Hofstede. Hofstede is an influential Dutch researcher well-known (in the social-psychology clique at least) for his research of cross-cultural groups and organizations. He played a major role in developing a framework for assessing and differentiating national cultures. Reading his jaw-dropping, hugely under-utilised trove of research has radically deepened my understanding of why we suck at breastfeeding in our society. It triggered an epiphany of sorts. And his book wasn’t even about breastfeeding!

I have always known that our culture is hostile towards breastfeeding at worst, and apathetic at best. Who’s to blame for this? I had all the usual suspects lined up: capitalism, the patriarchy, rampant individualism, formula company greed. However maybe the net of blame is far, far broader than I ever imagined.

Hofstede’s research revealed an interesting phenomenon: each country has a gender. A country’s culture is either predominantly masculine or predominantly feminine. The United States, for example, is deemed a ‘masculine’ country whereas Norway, for example, is a ‘feminine’ country.

Hofstede describes culture as “the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one group from another”. Whether a country is masculine or feminine describes the effects of that country’s culture on the values of its members, and how these values relate to behaviour.

Take a gander at this fairly inconspicuous-looking table. It shows a selection of countries and their respective masculinity ratings. Study it, worship it:

Notice that gender is rated on a scale of 1 to 100 with 1 being most feminine and 100 being most masculine. So the most feminine country is Sweden (with a rating of 5) and the most masculine country is Japan (rating of 95). No country is 100% masculine or feminine, rather most sway largely towards one gender.

Hofstede called this the ‘masculinity/femininity index’. It established a major research tradition in cross-cultural psychology and has also been drawn upon by researchers and consultants in many fields relating to international business and communication.

Okay, but what does this have to do with breastfeeding?

One important point that anthropologists have always made is that aspects of social life which do not seem to be related to each other, actually are related. Inspired by this belief, I cross-referenced Hofstede’s index with numerous breastfeeding studies and discovered some astonishing correlations! In a nutshell:

The masculinity/femininity of a society reflects a basic and enduring anthropological fact about that society’s approach to breastfeeding.

From my research into the gender of countries and how this impacts upon breastfeeding, five significant topics arose: Values, Family Life, Politics, The Media, and Women’s Liberation.

VALUES:

Masculine societies differ from feminine societies in their relative priority given to ‘ego’ versus social goals. So in a masculine society men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success; women are supposed to be more modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life. Conversely, in a feminine society, both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender and concerned with the quality of life. Interestingly, Hofstede found that whilst American females score as more feminine than American males, they also score as more masculinethan Dutch males. This illustrates how in masculine societies, male-ness is the normative standard, coveted by both men and women.

The distinction between masculine and feminine societies is even found at the basic level of how a country’s inhabitants communicate with one another. In masculine countries there is a predominance of ‘report talk’ – transferring factual information – versus ‘rapport talk’ in feminine countries – using conversation to exchange feelings and establish relationships. In the field of breastfeeding, we see these respective conversational styles reflected in the way health professionals and other breastfeeding advocates counsel mothers. In masculine countries breastfeeding support relies heavily on the presentation of ‘facts’ (the benefits of breastfeeding, how breast tissue functions, the mechanics of latching, etc), whereas in feminine countries there is emphasis not only on physiological detail but also on the psychological and social realities of breastfeeding. For instance, in the most feminine country in the world – Sweden, there is a widespread network of lay groups who provide breastfeeding support and a system of more experienced mothers who volunteer to be available to provide telephone support for new mothers (Sharples 2001). Also in addition to antenatal classes, all Swedish parents (both mothers and fathers) are encouraged to attend discussion groups and other ‘parent craft’ gatherings throughout their child’s early years (Larson 2008).

Feminine societies prefer to concentrate on strengthening relationships like this, and consequently, there is a lot less emphasis on ‘stuff’ (aka baby products) and a lot more emphasis on time spent with the baby. Meanwhile in a masculine society, the dominant values are money, material stuff and progress. These ethnocentric values have important implications for breastfeeding. The act of breastfeeding is intertwined with relationship maintenance and altruism. It is as far removed from materialism as one can get – there is no consumption involved, no cash payoff. Thus the mechanics of breastfeeding are in direct conflict with the values of masculine societies, whilst harmonising with the values of feminine societies. We see this reflected in the day to day child-rearing rituals of the respective cultures:

In feminine societies, it is assumed that mothers will want to breastfeed. There are few baby bottle decorations or baby bottle designs on shower invitations. Co-sleeping is common. Newborns aren’t swaddled and skin to skin is established practice. Babies are fed, not on schedule, but when they want. Infant formula is used only as an exception to the rule. Is it any surprise then, that Sweden is considered the global leader in terms in implementing the Unicef Baby Friendly Initiative: an international program for improving the role of maternity services to enable mothers to breastfeed. Four years after the programme was introduced in 1993, all of the then 65 maternity centres in Sweden had been designated “baby-friendly”.

And it’s not just babies that benefit from living in a feminine society; when Save The Children published a report revealing the best and worst places to be a mother in 2013, the top 7 countries were allhighly feminine on the Hofstede scale (Finland, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, Netherlands, Denmark and Spain respectively). In case you’re curious, the report assessed maternal well-being based on five factors: Maternal health; Under five mortality rate; Women’s education; Women’s income; Women’s political status (Save The Children 2013).

But wait, perhaps you’re thinking Japan is the most masculine society yet don’t Japanese women maintain a very close bond with their children much later than other Western parents, and don’t Japanese children typically cosleep much later? There is a common misconception that these factors automatically translate into robust breastfeeding rates, but sadly this is not the case. While the majority of Japanese mothers recognize some benefits of breastfeeding, their overall knowledge and attitudes towards breastfeeding are neutral at best and more positive towards the use of infant formula (Inoue et al 2013). Indeed, the overwhelming masculinity of Japan bears down, crushing breastfeeding rates. Japan is ranked far down on the Save the Children score chart at 31st for maternal well-being behind other masculine countries like the US and the UK, and unsurprisingly, Japan has even worse breastfeeding rates than those countries (ABC News 2007).

So what makes the United States’ and Japan’s treatment of mothers and babies pale in comparison to the Netherlands? One of the obvious differences between these countries is the latter’s welfare system. Americans consider the Dutch tax system – which makes the Dutch welfare system possible – as almost criminal. It effectively robs the Dutch of the opportunity to fulfil the goal of becoming rich. That Dutch people have a different set of values, expressed in a willingness to pay higher taxes to maintain a welfare state, is hard for many Americans to understand. Yet caring for other people is one of the dominant values in feminine societies such as the Netherlands. Which brings us to…

FAMILY LIFE:

Feminine societies encourage both men and women to be tender and to be concerned with family relationships. Conversely, masculine societies expect only women to show these attributes. Perhaps unsurprisingly then, parenthood is more positively valued in feminine than in masculine cultures, and the well-being of children plays a more important role in parents’ ways of arranging their lives.

For example, when given the choice between higher salaries versus shorter working hours, both men and women from masculine countries preferred higher salaries. We can see how this would affect breastfeeding rates: the more hours a mother spends working, the less direct contact she has with her child to maintain supply. Similarly, the more hours a father spends working, the less direct contact he has with his family in order to support the breastfeeding relationship. In masculine societies many mothers are slaves to the office breastpump. Whereas for mothers in feminine countries, pumping is rare due to generous parental leave facilitated by a culture which prioritises family well-being.

In masculine societies the dominant ethos is that you ‘live in order to work’. In feminine societies you ‘work in order to live’. In the workplace of a feminine society, equality, solidarity, and quality of work life are stressed. Meanwhile in the workplace of a masculine society, equity, mutual competition and performance are stressed. When people feel pressured to perform and compete, they are compelled by their society to prioritise career over family life.

Whilst both men and women in masculine societies are expected to be competitive in the workplace, the same cannot be said for home life. Domestic and caring responsibilities are, on average, significantly less equally distributed in masculine societies. For instance, masculine societies are apt to downplay or neglect fathers’ roles in the facilitation of breastfeeding. Numerous studies have highlighted the reluctance of masculine societies such as the United States, the UK and Australia to recognise the father’s role in breastfeeding support (Tohotoa et al 2009; Rempel and Rempel 2010; Sherriff et al 2011; Vaaler et al 2011; Maycock et al 2013; Allcutt 2013). The existence, or absence, of paternal support can often ‘make or break’ the success of the breastfeeding relationship.

In masculine countries ‘Family Values’ are a reference to religion and tradition. In feminine countries on the other hand, Family Values mean time with your family. With long working hours and minimal parental leave as staples of masculine society it should come as no surprise that feminine societies are much more child-centered. The freedom, care and ability to ‘just be a kid’ is an essential part of childhood in feminine countries. This is complemented by access to quality health care without the stress of worrying about being hit by strange bills, quality daycare, schools, and University education. In Hofstede’s words: “Masculine societies have sympathy for the strong, whereas feminine societies have sympathy for the weak.”

In feminine countries, babies are allowed to develop at their own pace; to attempt to ‘discipline’ them in matters that they cannot understand is considered a mark of parental ignorance. In fact, in 1979, the Swedish parliament passed a law forbidding corporal punishment, making Sweden the first nation in which parents were forbidden to strike their children. The law is widely known and accepted.

However in masculine countries a degree of ‘baby training’ is the norm, with sleep and feeding schedules commonly advocated by experts. In the US for example, the belief that children – even newborns – are manipulative of their parents is quite common. Mothers must resist “giving in” to their babies’ (unreasonable) “demands” for fear of spoiling them. Babies cannot be trusted to know and communicate their fundamental physiological, psychological, and developmental needs (La Leche League 2000). Beliefs such as these interfere with breastfeeding by discouraging mothers from picking up their babies and breastfeeding them whenever they root or cry. In masculine countries bottles are introduced to infants so that others can feed, pushing babies towards premature independence and facilitating the separation of mother and child. Pacifiers are also introduced so the child will not depend on mother for all his suckling needs, which in turn diminishes breastmilk supply.

THE MEDIA:

A characteristic of feminine culture is scepticism and dislike of ‘hype’. Advertising in general is exaggerative by nature, which arouses scepticism in the consumers of feminine countries. This cultural trait makes the inhabitants of feminine countries less receptive to marketing, and this is good news for breastfeeding. In fact, in Scandinavia (Denmark, Sweden and Finland – all feminine countries) follow-on milk promotion is banned. In Norway (the second most feminine country in the world) all advertising of artificial formula milk is banned completely.

In line with this scepticism, sex and violence in the media are taboo in feminine societies, whereas these acts frequently appear in the media of masculine societies. In the UK, recent campaigns have highlighted the prevalence of such media and its negative impact on breastfeeding rates (see: Ashton 2013).

Over in feminine societies, breasts are everywhere, but often in non-sexual ways. Breastfeeding in public is the norm. In fact, a mother using a hooter-hider American-style would be considered bizarre in Sweden.

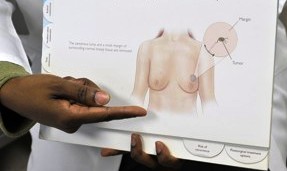

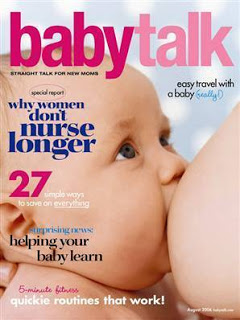

In masculine countries, the sight of a baby latched at its mother’s breast is cause for outrage. For instance in 2006, the editors of US BabyTalk magazine received many complaints from readers after the cover of the August issue depicted a baby nursing at a bare breast. Even though the model’s nipple was not shown, readers—many of them mothers—wrote that the image was “gross”. In a follow-up poll, one-quarter of 4,000 readers who responded thought the cover was negative (NBC News 2006). In a 2004 survey conducted by the American Dietetic Association, only 43% of the 3,719 respondents believed women ought to have the right to breastfeed in public.

Meanwhile in 2010 in the UK, another highly masculine country, the deputy editor of leading parenting magazine Mother & Baby described breastfeeding as “creepy.” Kathryn Blundell told readers that she bottlefed her child from birth because, “I wanted my body back [and] to give my boobs at least a chance to stay on my chest rather than dangling around my stomach.”

Then of course, there’s the ethnocentric dictator we call Facebook. The US online social networking site described photos of breastfeeding (baby latched on, no nipple visible) as ‘indecent’ and promptly deleted them from the site while cancelling the Facebook accounts of the mothers in question. The company said it removed the photos because they violated the ‘pornographic’ rules in the company’s terms and conditions (Moses 2007).

POLITICS:

In politics, feminine societies believe that preservation of the environment should have the highest priority, whereas masculine societies believe highest priority should go to economic growth. We see this played out in relation to formula trading. Formula consumption contributes to economic growth (in the form of generating wealth for the few) whilst causing environmental decay. Correlatively formula companies’ hold dominance in the market of masculine societies. In Mexico for example (masculine country with a ranking of 69) the government currently pays about $35 million a year on cans of infant formula from Nestle, which receives more than 96 percent of the public money spent on formula (Fox News 2013). Whereas the presence of formula companies in the markets of feminine societies is slim to none. In fact, the supermarkets in feminine countries offer limited stock because demand is so low.

Masculine societies value consumption and the production of goods, and the formula trade complements this paradigm nicely; whereas, breastfeeding reduces consumption and does not produce any goods. Conversely, the lesser importance placed on economic growth by feminine societies, along with their higher value placed on environmental preservation makes feminine societies a perfect fit for breastfeeding.

It is interesting to note that despite the converse priorities given to economic growth by masculine and feminine societies, the gender of a country is entirely unrelated to national wealth: there are just as many poor as there are wealthy masculine, or feminine, countries. Differing priorities do not necessarily produce disparities in wealth.

WOMEN’S LIBERATION:

When it comes to the stormy issue of ‘women’s liberation’ both feminine and masculine societies have their own idea of what it means. Feminine societies interpret women’s liberation as meaning that men and women should take equal shares both at home and at work. Masculine societies think differently. They translate women’s liberation to mean permitting women to enter positions hitherto occupied by men.

Exploiting this cultural mannerism, formula companies in masculine countries market their products as enabling the independence of mothers. Competing with men is what women’s liberation looks like through a masculine lens. Whereas in feminine countries, a ‘complementary’ approach to liberation stresses the interdependence between male and female roles.

We see this reflected in the amount of paid and unpaid parental leave for mothers and fathers sanctioned in each society. For instance, in feminine societies, employers now expect their employees to take parental leave no matter their gender.

Sweden (the most femineine country with a Hofstede rating of 5) provides working parents with an entitlement of 16 months paid leave per child at 80 percent pay, the cost being shared between employer and the state (Sternheimer 2010). To encourage dads to take a greater paternal involvement in child-rearing, 2 months out of the 16 is reserved for the “minority” parent, in practice usually the father, and some Swedish political parties on the political left are pushing for legislation to oblige families to divide the 16 months equally between both parents (forsakringskassan 2013). 80% of fathers now take a third of the total 13 months (Bennhold 2010). This is in line with the characteristic of feminine societies encouraging both men and women to be tender and to be concerned with relationships. Norway, another highly feminine country (rating 8), has similarly generous leave (Norwegian Embassy 2013).

How about feminine countries with slightly more masculine leanings? (Say, those with a 30-40 rating on the Hofstede scale). In Estonia (30 rating) mothers are entitled to 18 months of paid leave. Fathers are entitled to paid leave starting from the third month after birth (paid leave is however available to only one parent at a time). In Bulgaria (40 rating) a father can take the whole of a mother’s maternity leave and receive 100 percent salary for a full year. Interestingly Portugal (rating of 35) is the only country in the world to have mandatory paternity leave (albeit only a week in length).

In comparison, how do more strongly masculine countries operate their parental leave? Hofstede considers any country with a rating over 60 to be strongly masculine. In the UK (rating of 66), female employees are entitled to 52 weeks of partly-paid maternity (or adoption) leave, whilst fathers are only entitled to 2 weeks partly-paid paternity leave. This discrepancy between maternity and paternity leave is in line with the characteristic of masculine societies believing that predominantly only women should be tender and to be concerned with relationships. We see the same discrepancy in other masculine countries. Lebanon (rating of 65), gives mothers 7 weeks of maternity leave at full pay, whilst giving fathers only one measly day at full pay. The Philippines (rating of 64) gives mothers 60 days of leave at full pay (78 days for c-section deliveries) whilst fathers only get 7 days leave at full pay and interestingly, the father must be married to get this!

Canada is a more androgynous country with a slight masculine leaning (rating of 52). In addition to 15 weeks maternity leave, parents in Canada get 35 weeks leave which can be divided between both mother and father in any way they like.

How does this relate to breastfeeding? You’ll not be surprised to read that mothers returning to work in the first 6 weeks are less likely to breastfeed, and if they do, the period of breastfeeding is significantly shorter than other groups who returned to work between 7 to 52 weeks (Tanaka 2005). In general, the longer the parental leave, the longer the rate of breastfeeding (Berger et al 2002). This is not only true of maternity leave but also true of paternity leave. Fathers’ presence facilitates breastfeeding success (Tohotoa et al 2009; Rempel and Rempel 2010; Sherriff et al 2011; Vaaler et al 2011; Maycock et al 2013; Allcutt 2013).

So, how does your country measure up?

To see how the masculinity/femininity of a country measures up to its breastfeeding prowess, let’s look at the raw data from four countries: the UK, the US, Sweden and Norway:

United Kingdom:

At 66 on the Hofstede scale Britain is a masculine society – highly success oriented and driven. Hofstede comments:

“A key point of confusion for the foreigner lies in the apparent contradiction between the British culture of modesty and understatement which is at odds with the underlying success driven value system in the culture. Critical to understanding the British is being able to ‘read between the lines’. What is said is not always what is meant. In comparison to feminine cultures such as the Scandinavian countries, people in the UK live in order to work and have a clear performance ambition.”

Breastfeeding stats: At three months, the number of mothers breastfeeding exclusively in the UK is 17% and at four months, it is 12%. Exclusive breastfeeding at six months remains at a depressing 1%. (Unicef 2010).

United States:

The United States score 62 on the Hofstede scale and is considered a “masculine” society. Hofstede comments:

“In America behaviour in school, work, and play are based on the shared values that people should “strive to be the best they can be” and that “the winner takes all”. As a result, Americans will tend to display and talk freely about their “successes” and achievements in life, here again, another basis for hiring and promotion decisions in the workplace. Typically, Americans “live to work” so that they can earn monetary rewards and attain higher status based on how good one can be. Conflicts are resolved at the individual level and the goal is to win.”

Breastfeeding rates: At three months, the number of mothers breastfeeding exclusively in the US is 46.2% and by six months the number drops to 25.5%. The number of US babies receiving any breastmilk at 1 year stands at 34.1% (US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2012).

Sweden:

Sweden scores 5 on the Hofstede scale and is therefore a feminine society. Hofstede comments:

“In feminine countries it is important to keep the life/work balance and you make sure that all are included. An effective manager is supportive to his/her people, and decision making is achieved through involvement. Managers strive for consensus and people value equality, solidarity and quality in their working lives. Conflicts are resolved by compromise and negotiation and Swedes are known for their long discussions until consensus has been reached. Incentives such as free time and flexible work hours and place are favoured. The whole culture is based around ‘lagom’, which means something like not too much, not too little, not too noticeable, everything in moderation. Lagom ensures that everybody has enough and nobody goes without. Lagom is enforced in society by “Jante Law” which should keep people “in place” at all times. It is a fictional law and a Scandinavian concept which counsels people not to boast or try to lift themselves above others.”

Breastfeeding rates: At three months, the number of mothers breastfeeding in Sweden is 80% and by six months the number is 67% (Statistik om amning 2010).

Norway:

Norway scores 8 on the Hofstede scale and is thus the second most feminine society (after the Swedes). Hofstede comments:

“This means that the softer aspects of culture are valued and encouraged such as leveling with others, consensus, “independent” cooperation and sympathy for the underdog. Taking care of the environment is important. Trying to be better than others is neither socially nor materially rewarded. Societal solidarity in life is important; work to live and DO your best. Incentives such as free time and flexibility are favoured. Interaction through dialog and “growing insight” is valued and self development along these terms encouraged. Focus is on well-being, status is not shown. An effective manager is a supportive one, and decision making is achieved through involvement.”

Breastfeeding rates: At three months, the number of mothers breastfeeding in Norway is 87% and by six months the number is 80% (Småbarnskost 2-åringer 2009).

Your country not listed here? You can discover whether your country is masculine or feminine at Hofstede’s site HERE and compare it with your country’s breastfeeding rates on the Unicef site HERE.

Anaïs Nin, a French-born novelist, once remarked:

“We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are”.

Nin’s sentiment perfectly captures the essence of ethnocentrism: we view human behaviour through the lens of our particular cultural experiences.

However if we adopt a cultural-relativistic perspective, we are confronted with a sobering truth: breastfeeding success is largely dependent on simply being born in the ‘right’ country.

Postscript: Apologies to Swedish border control, who will now be flooded with a barrage of crunchy American moms seeking to emigrate.