A little while ago I posted an article titled, ‘It’s Just Baby Fat’, in which I ridiculed a grotesque toy doll that came armed with a toy bottle. I linked the baby’s obese frame with the suggestion that it was formula fed.

The response to this post was overwhelmingly one of contemptuous anger (really? One of my posts?! Never!)

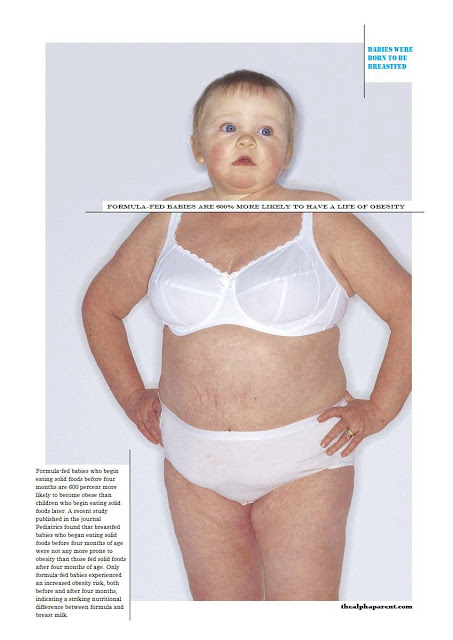

Likewise, this mock health advertisement which I posted on The Alpha Parent Facebook page was greeted with similar disdain:

Here’s the deal: during the first 6 to 8 weeks of life there is little difference in growth (gain in weight and length) between breast- and formula-fed babies. However, from about 2 months of age formula-fed infants gain weight and length more rapidly than breast-fed infants (Ziegler 2006; Singhal 2007; Rebhan 2009; Larnkjaer et al 2009; Durmuş et al 2011; Rose et al 2012). Numerous studies have shown that by the end of the first year breastfed babies are leaner than formula-fed babies (Lande et al 2005; Tantracheewathorn 2005; Oddy et al 2006; Scholtens 2008; Stuebe 2009; Van Rossem 2011; Mindru and Moraru 2012; Arenz et al 2004; Mayer-Davis et al 2006; Plagemann and Harder 2011). Scientists suggest that the rapid weight gain among formula fed babies likely represents fat mass gain (Wells et al.,2007; Karaolis-Danckert et al., 2006).

Now, you’ve no doubt heard the DFF (Defensive Formula Feeder) often-regurgitated defence to these statistics: “Line up some school kids and you won’t be able to tell whose been breastfed and whose been formula-fed”. However, I beg to differ – we can make a pretty good bet, and science agrees. In a 2008 study, researchers looked at school entry data of 14,412 children aged 4.5–7 years in southern Germany. After adjusting for a large number of potential confounding variables, mean BMI was significantly reduced in children who had been breastfed versus the formula-fed (Beyerlein et al 2008). Another, even more recent study, showed that the effects of prior breastfeeding on protecting from obesity were particularly significant at ages 6 to 13 years (Crume et al 2012). Similar results were reported from 2 to 14 year old children in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (Li et al 2005).

So formula fed babies *are* fatties, not just now, but throughout life. Why?

Reason #1 Species Specific

concentration of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (Shahkhalili et al., 2011). Also, when solids are introduced the fat composition changes dramatically. Intakes decline from around 50% of total energy in breastmilk to 30–35% of total energy (Thompson 2012).

Reason #2 Natural Vs Synthetic:

It should come as no surprise that whether your baby derives nourishment from a natural or synthetic source will impact on the way their body behaves. Unlike formula, breastmilk is alive and contains hundreds of non-nutritive components which studies have agreed “influence short and long-term patterns of growth through their regulation of nutrient use and metabolism” (Hamosh, 2001). For instance, did you know that the higher levels of LCPUFAs (long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids) in breastmilk are associated with lower glucose levels in the skeletal muscle and reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cells (Das, 2002). Also, breast milk contains endocannabinoids! Nope, you didn’t start hallucinating. This lactogen, which can cause the munchies (presumably to entice babies to feed), also regulates appetite, making them feel very full at the end of a feed. Consequently, they don’t over-eat (Williams 2013). Formula lacks these compounds. What’s more, longer durations and exclusivity of breastfeeding enhance these effects in a dose–response manner (Harder et al., 2005) with the lowest risk seen among those breastfed longest without formula supplementation (Arenz et al., 2004). Researchers have suggested that this link between the fatty acid profile of breastmilk and inflammation may be particularly important given the well-established links between systemic inflammation and the development of obesity (Thompson 2012; Dandona et al., 2004; Yudkin, 2007).

Another positive of being natural is that “unlike formula, breastmilk composition varies between mothers, over the course of lactation, and during feeds, providing a mechanism through which the baby’s energy needs and feeding behaviors, such as frequency and duration of feeds, can directly influence weight gain during on-demand breastfeeding” (Thompson 2012). Your baby controls the quantity and consistency of their milk intake and your body provides a unique blend of micronutrients tailed specifically to your baby’s requirements. Under such conditions, it’s not hard to see why obesity is unlikely in breastfed babies.

Consider also that breast milk changes in composition during the feed (aka the fore/hind milk dichotomy). This mechanism actually helps a baby to know when he has had enough. Depending on how hungry he is the baby can choose to take in more or less of the rich hind milk, which comes at the end of the feed.

Reason #3 Mode of Delivery

This is perhaps the most commonly cited explanation for formula-fed babies proneness to obesity. Simply: breastfeeding puts your baby in the driving seat. He has full control over the amount of milk he takes (Fisher et al., 2000). Because he has to work hard to get the milk, he will stop when he has had enough. Consequently his stomach does not become overstretched.

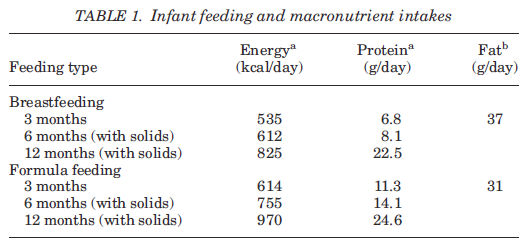

Breastfeeding also promotes maternal feeding styles that are less controlling and more responsive to infant cues of hunger and satiety, thereby allowing infants greater self-regulation of energy intake (Taveras 2006). The contrary is true of formula fed babies, who are more prone to over-feeding and thus, to stomach-stretching (Ruowei Li et al 2012; Brown and Lee 2012; Fein and Grummer-Strawn 2010). For instance, six-week-old formula-fed infants consume 20–30% higher volumes per feed and, by 4 months, have fewer yet much larger feeds (Sievers et al., 2002). Differences in the volume consumed and the higher energy density of formula contribute to a whopping 15–23% higher total energy intake in formula-fed infants from 3 to 18 months (Thompson 2012). When a baby’s stomach is overstretched regularly, he becomes accustomed to this ‘full feeling’. He then expects this feeling each time he feeds and this often becomes the habit for life, leading to overeating (Lim 2009).

Research has shown that differences in intake between breast and formula fed babies persist well after solid foods are introduced (Dewey, 2009). Each additional 100 kcal/day that formula fed babies consume at 4 months is associated with 46% higher odds of them becoming overweight at 3 years and 25% higher odds at 5 years (Ong et al., 2006). These facts add credence to the hypothesis that breastfed babies better match intake to energy needs while their formula fed counterparts seem unable to compensate for the intake of solids with lower formula intake (Wasser et al., 2011).

Reason #4 Leptin and Ghrelin

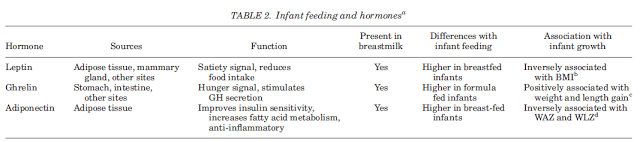

Interestingly, researchers have asserted that: “The presence of hormonal differences between breast- and formula-fed infants provides evidence that feeding type has a metabolic effect in infants” (Thompson 2012). Let’s explore this statement further.

The hormonal composition of breastmilk plays an important role in the neural programming of appetite, not just in short-term regulation of infant weight gain, but also in long-term programming of the complex pathways linking the hypothalamus, gastrointestinal tract, and fatty tissues (Agostini, 2005; Savino et al., 2009; Bartok and Ventura, 2009).

The hormones Leptin and Ghrelin are key players in ‘programming’ the human appetite and nutritional preferences. Leptin is the hormone responsible for making us feel full. The levels of leptin in breastmilk become more plentiful as the baby reaches the rich hindmilk (Savino et al., 2009). When ingested during the suckling period Leptin is absorbed by the baby’s immature stomach exerting certain biological effects. These include: facilitating the normal maturation of tissues and signalling pathways involved in metabolic processes; programing appetite by providing hunger and satiety cues; discouraging excessive fat storage; and improvement in insulin sensitivity (Agostoni 2005; Savino and Liguori 2006; Palou and Picó 2009; Vickers and Sloboda 2012; Thompson 2012).

The other hormone in this duo – Ghrelin – is produced by the stomach and functions as a hunger signal. Formula fed babies have higher ghrelin levels which links formula feeding to increased appetite. (Savino et al., 2009).

These findings are in line with other studies which maintain that neonatal nutrition influences endocrinology more readily than genetics (Zegher et al 2012).

Reason #5 Growth Hormone

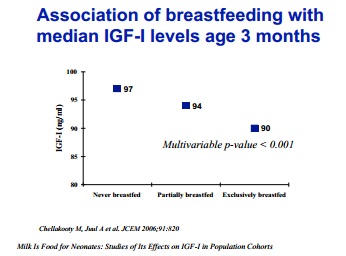

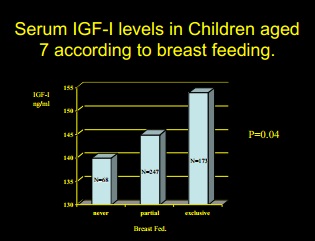

Conversely, as you can see in the above charts, breastfed babies have lower levels of IGF as babies, but at 7 to 8 years they have higher levels of IGF-1 (Martin et al 2005; Savino and Lupica 2006). This suggests that during the breastfeeding period, the lower IGF-1 levels have reset the hypothalamic/pituitary axis to a higher responsiveness to increased growth hormone as an inference (Larnkjaer et al 2009; Michaelsen et al 2012).

These findings are in line with other studies which maintain that being breastfed for between 13 and 25 weeks is associated with a 38 percent reduction in the risk of obesity at nine-years of age, while being breastfed for 26 weeks or more is associated with a 51 percent reduction in the risk of obesity at nine-years of age (McCrory and Layte 2012; Gillman et al 2001; Mayer-Davis et al 2006; Weyermann et al 2006; Abraham et al 2012).

What About Environment?

Everything I have discussed above is married with the environment in which it occurs – and that environment is usually one of abundant over-nutrition. Formula fed babies have the worst of both worlds. They are physiologically disadvantaged due to all the factors explored above, and they are environmentally disadvantaged by a culture which is out of sync with nutritional health.

During infancy, babies’ bodies try to adapt to their environment. The endocrine system is part of that adaptation. Assume you are a formula fed baby. If you are trying to adapt to an environment of high protein intake (formula) that is driving your IGF-1, your IGF-I levels will feed back and suppress the central control, re-setting this control under the assumption that you will always have a high protein intake. So you come out of this high protein exposure with a pituitary that has been re-set down.

With all these factors in mind, we see how formula fed babies have the odds stacked against them from the start. However when studies are published which show that feeding a human infant with artificially modified bovine milk (i.e. formula) leads to obesity, formula feeders are up in arms. “Correlation does not equal causation!” they chant. This is a lazy get-out clause used to denounce scientific evidence. The dialogue often goes like this:

Science: “Formula feeding increases a child’s risk of becoming obese”.

Formula feeder: “No. My child was formula fed and they’re not fat”.

Science: “Scientific studies have shown that children who were formula fed are statistically more likely to become obese. The increase in formula use correlates with the parallel increase in obesity”.

Formula feeder: “It’s not formula feeding that is responsible for the rise in obesity – it’s people eating too much fattening food!”

Science: (Trump card time) “Formula feeding manipulates a baby’s biological makeup, priming their body’s receptiveness to putting on weight.”

Indeed, these metabolic and physiological processes have a more central role in obesity than social trends. Whilst it’s true that breastfeeding mothers are statistically more likely to be higher educated, afford healthier food, and make better food choices for their families – these factors don’t negate the bioactive factors inherent in breast and formula feeding. In light of the scientific evidence it is impossible to deny the dynamic interplay of groups of hormones with cellular chemistry, protein composition and appetite regulation mechanisms, all of which expose the true nature of formula feeding as an instrument of sabotage in the fight against obesity.